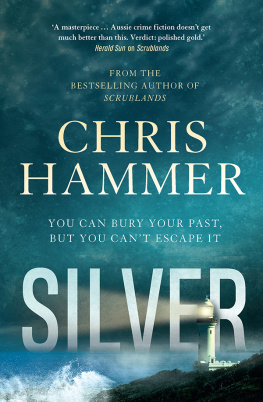

THE RIVER

THE RIVER

A Journey through the Murray-Darling Basin

CHRIS HAMMER

For Tomoko, Cameron and Elena

Contents

Map of the Murray-Darling Basin

Diagram of the Murray River System

Prologue

The Finniss River Recreational Boating Destination

I drive north on the highway for about 10 kilometres before turning off onto a secondary road. After months of dry the rain is sweeping inland off the Southern Ocean in intermittent squalls, and I drive slowly, forced to squint past the wipers. A few more kilometres and I turn off again, onto gravel. After months of travelling the river catchments, Ive developed a nose for this sort of thing, understanding the lay of the land: where the roads follow ridges, where they curve around them, and where they dip to meet the waterways. Ive learnt where to look for the water, where the subtle tug of gravity has taken it, carving gullies and creeks, rivers and streams as it goes. I look for another road, hoping there will be one, that will take me from the engineers heights to natures low, from the road to the water. The rain pauses and just such a road appears on my left, as if on cue. Tonkin Road its called. Not much more than a track, really. But its taking me towards the water, or towards where it should be, to where it once wasthe water that has lain in this landscape for seventy years, and ebbed and fl owed for thousands of years before that; the water that has gone.

Six months ago I wouldnt have recognised the significance of the view off to the left as I ease the car down Tonkin Road: just another dry creek bed running through just another field. I continue down to where the road stops. The drizzle returns, the day ironically grey, yet the evidence is clear for all to see. I cant help smiling at the jetties. The three of them look so ridiculous in their empty field, raised 3 metres above the dry creek bed. A sign says: Finniss River Recreational Boating Destination This facility is provided for picnics and overnight stops for people with recreational craft. I stand on one of the jetties and look towards the horizon, to where the water must be, but theres little chance of seeing any of it; the diminishing shoreline of Lake Alexandrina, the larger of South Australias two lower lakes, must be at least 2 kilometres away. The lakes lie at the end of the Murray River, just before it enters the sea. Or rather, just before it used to enter the sea.

I clamber down from the jetty into the creek bed where the black soil lays cracked and exposed, like a farm dam at the end of summer. Something white lying against the black of the soil catches my eye: the broken shell of a freshwater mussel, as incongruous in this farmers field as the jetties. Deja vu. As I crouch to examine it, the wind drops and I catch the smell: a hint of sulphur. Perhaps the misting rain is interacting with the exposed acid sulphate soil to form sulphuric acid. Thats the great fear: that the residual pools of the lakebed will turn to battery acid; that the lower lakes will become irredeemably toxic; that the Murray will be dead before it reaches the sea, even if the water does some day return.

I had thought myself well prepared before I began this journey along the rivers six months ago. Id been perched up in the Canberra Press Gallery for the best part of a year writing on the environment: collecting the data, speaking to the experts, listening to the political debatethe view from above. Id become familiar with the Murray-Darling, Australias largest and most important river system, despite rarely venturing out into it. Id reported on Garnaut, on government green and white papers, on multibillion-dollar water buybacks, on new deals between the federal and state governments, on the ever-shrinking water allocations for irrigators, on the slow death of the wetlands. Id watched ringside as politicians engaged in their slippery wrestle for ascendancy, and had them visit my desk to convince me of their well-rehearsed truths. Id listened to environmentalists, farmers, industrialists and scientists. Every second month, Id faithfully left Parliament House to visit the headquarters of the Murray-Darling Basin Commission and hear the ever-grimmer drought updates and the arid predictions of the Bureau of Meteorology. I could talk giga-litres and allocations and diversions with the best of them. I knew my way round the facts: that the Murray-Darling is Australias food bowl, supplying some 40 per cent of our agricultural output and supporting some two million inhabitants, plus providing drinking water to a million more in Adelaide. I also knew the prognosis: Ross Garnauts warning that unconstrained climate change would end agriculture in the basin and effectively depopulate it within a century. But every now and then Id gaze westward through the hermetically sealed windows of Parliament House, looking to the sometimes snowcapped Brindabellas, and Id wonder what was happening on the far side of the range, whether the rivers fl owing off towards South Australia could possibly be half as dry as the statistics clogging the desk in front of me.

Not that the information hasnt been useful. The maps taught me the basic geography of the basin. They declare that the Murray-Darling system covers a huge swathe of Australia: one-seventh of the continents land mass; more than a million square kilometres, almost three times the size of Germany. They show the basin stretching from southern Queensland to contain almost all of New South Wales west of the coastal mountains, much of the Victorian hinterland and a crucial swathe of riverland in the east of South Australia. Some maps divide the system into twenty-three separate river catchments, feeding one into another until they eventually flow together into the South Australian Murray and from there to the Southern Ocean. Other maps divide the system into the Northern and Southern Basins, suggesting that what happens in one might have little or no impact on the other. These maps reveal the Northern Basin to be more than twice as big as the Southern Basin; it feeds the Darling River, the sole connection between the two basins. The Northern Basin begins in Queensland, extending west from the Great Dividing Range along the Condamine-Balonne-Culgoa catchment and the Barwon River. The Barwon becomes the main stem as more rivers join from the east: the Gwydir and the Namoi of northern New South Wales, and, from further south, the Castlereagh, the Macquarie and the Bogan, the water coming from as far south as Bathurst, directly west across the Blue Mountains from Sydney.

The maps display, without explaining why, the rivers curious ability to change names. Up near one rivers headwaters, its called the Condamine before becoming the Balonne, and eventually the Culgoa. Where the Culgoa joins the Barwon, both names are discarded and the Darling is born. By the time the Darling reaches Bourke in far western New South Wales, it has gathered in all its eastern tributaries. Only the outside rivers remain, the Warrego and the Paroo, which flow down from the Queensland desert to join the Darling south of Bourke. The Darling joins the Murray at Wentworth, not far east of the South Australian border.

Although the Northern Basin is massive, its the Southern Basin where most of the water and three-quarters of the irrigation is found. Its also where the crisis of drought is most keenly felt, and where the climate change predictions are grimmest. The maps show the major rivers of the Southern Basin flowing from the mountains of the Great Dividing Range: the Lachlan and the Murrumbidgee in New South Wales, the border-defining Murray, and the shorter but water-rich rivers of Victoriathe Kiewa, the Ovens, the Goulburn, the Campaspe and the Loddonpushing north-west to join the Murray. But the maps dont necessarily show the underground tunnels of the Snowy Mountains Scheme, diverting water from coastal rivers through the mountains to feed the Murray and the Murrumbidgee. By the time the Murray has reached Mildura it has collected almost all its tributaries. The last to join is the Darling, but very little of the water that flows onwards into South Australia comes down it; most of the water originates in the Australian Alps, the forested range extending down past Canberra to the New South Wales snowfields, and on into Victoria, towards Melbourne. More than half the water in the Murray-Darling Basin comes down the Murrumbidgee, the Goulburn, the Loddon, the Broken and the Murray, originating in a catchment less than a seventh the size of the entire basin.

Next page