Quarterly Essay is published four times a year by Black Inc., an imprint of Schwartz Books Pty Ltd. Publisher: Morry Schwartz.

ISBN 9781760642280 ISSN 1832-0953

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior consent of the publishers.

Essay & correspondence retained by the authors.

Subscriptions 1 year print & digital (4 issues): $79.95 within Australia incl. GST. Outside Australia $119.95. 2 years print & digital (8 issues): $149.95 within Australia incl. GST. 1 year digital only: $49.95.

Payment may be made by Mastercard or Visa, or by cheque made out to Schwartz Books. Payment includes postage and handling.

To subscribe, fill out and post the subscription form inside this issue, or subscribe online:

quarterlyessay.com

Phone: 61 3 9486 0288

Correspondence should be addressed to:

The Editor, Quarterly Essay

Level 1, 221 Drummond Street

Carlton VIC 3053 Australia

Phone: 61 3 9486 0288 / Fax: 61 3 9011 6106

Email:

Editor: Chris Feik. Management: Elisabeth Young. Publicity: Anna Lensky. Design: Guy Mirabella. Assistant Editor: Kirstie Innes-Will. Production Coordinator: Marilyn de Castro. Typesetting: Akiko Chan.

CRY ME A RIVER | The Tragedy of the MurrayDarling Basin |

Margaret Simons |

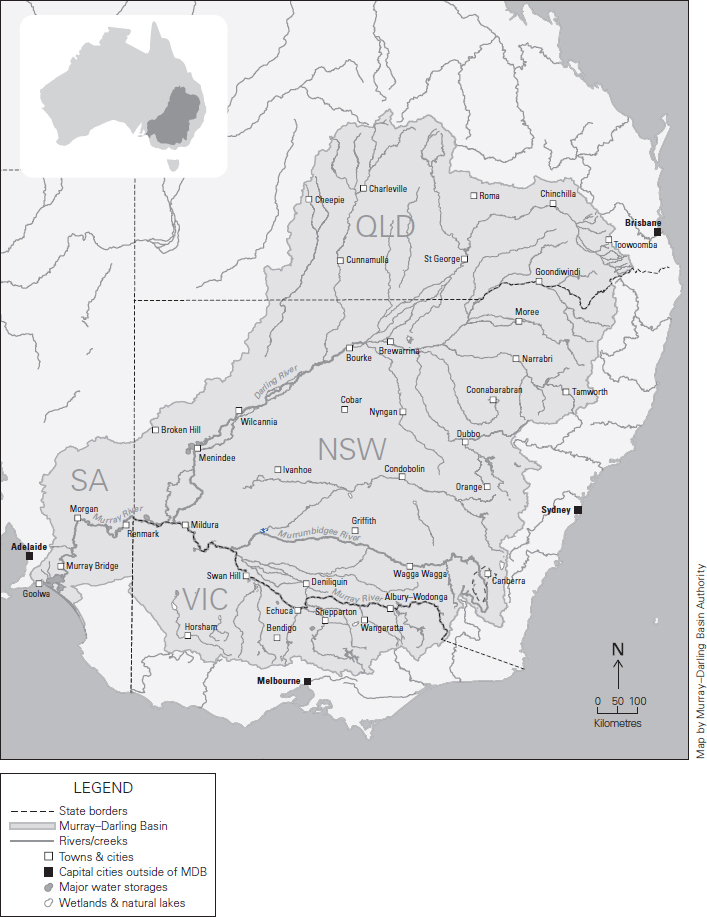

Ive come to think of the MurrayDarling Basin as being like a tree, except the sap runs not from root to twigs but in the other direction. The roots and trunk are in South Australia. Here the river runs pea-green between red cliffs through semi-desert country to the vast sheets of water that form the lower lakes, the Coorong and the sea. The main branches of the tree are the Murray itself, forming most of the border between New South Wales and Victoria, fed by the mighty Murrumbidgee and its tributaries and the rivers of Victoria. The other main branch is the Darling, or the BarwonDarling, to give it both its northern and southern names. Its tributaries loop to the Great Dividing Range west of Sydney and splay into the braided floodplains of the tropics. The smaller branches and twigs spread across the inland, each one with a story, or many stories. Clancy of the Overflow, who worked on the Lachlan River before he went to Queensland droving down the Cooper River, where the western drovers go. The Drovers Wife, who lived by a dried-up creek in the Henry Lawson story. It was probably a tributary of the Darling, although recent reimaginings relocate her to the Snowy Mountains. The European names of the rivers are gestures to the history of white nation-building Lachlan, Macquarie, Darling, the Murray itself.

There are older stories. The Rainbow Serpent, which in the stories of the Barkandji lives in the waterholes of the Lower Darling, or the Barka as they prefer to call it. Or Ngurunderi, whose pursuit of Ponde a Murray cod created the channel of the Lower Murray.

You can give the figures 77,000 kilometres of rivers, 2.6 million people, forty Aboriginal nations, 120 species of waterbirds but they are abstractions from the reality.

It seems wrong that the word basin is so utilitarian, conjuring up images of kitchen implements and dishwater. This is a mighty thing. It covers more than a million square kilometres. One of the things that makes it hard to understand, to conceptualise, is its size. The water engineers call it one of the largest drainage areas in the world, which again makes one think of sinks and plugholes.

But it can also be thought of as a vast, cupped hand. This is how Badger Bates, a Barkandji elder, describes it. He was raised on the Barka and taught the traditional ways by his grandmother and extended family. He grew up to be a stockman and a park ranger. He says he never learnt to read and write properly, but today, at seventy-three, he carries himself with a natural authority that the bureaucrats and politicians struggling to govern the Basin can only envy. He stretches out his arm. Here is my left hand, and in my palm the Barka starts. And here my fingers running to my palm are the Warrego, the Barwon, the Culgoa. Then here, my thumb joint, that is Wentworth, where the Barka meets the Murray. Then across where my left arm meets my shoulder, my body beyond he gestures to his chest, his skinny, hardened torso that is South Australia, right down to them lakes. And my right arm, here runs the Murray. So, our duty as Barkandji people is to fight for this river, to give them all water. We are connected.

But at the moment, and too many times in the last decade, the Darling doesnt run.

Water connects people, but it also divides. If politics is how human societies decide on the sharing of resources, wealth and power, then in a dry country water is indubitably, essentially and unavoidably political. The Basin and its water politics are in the news because of allegations of corruption and water theft, because of dead fish and angry irrigators, and because a royal commission in South Australia has suggested one of our important government organisations, the MurrayDarling Basin Authority, is dishonest, incompetent and acting outside the law. The narrative concerns the MurrayDarling Basin Plan and its implementation. To the management of the MurrayDarling we can attribute the rise of the Shooters, Fishers and Farmers Party, and an increasing atmosphere of panic mixed with vaunting ambition in the National Party, extending into the Coalition. And, most likely, Labor will not be able to win government unless it can address water politics, and with it one of the political fractures of our time: the divide and mutual incomprehension between those who earn their living directly from land and resources and those who dont.

There is a conventional, city-based view of rural Australia as locked in a time warp, unchanging and resistant to change. It is a dangerous and sentimental misunderstanding as simplistic and out of touch as its rural-based counter, the view of city folk as soft-handed, soft-headed and divorced from hard realities. The speed of change for those who learn their living from the land outstrips anything city dwellers have dealt with in recent decades. Technology and mechanisation has devastated rural employment. New cropping methods laser ploughing, preserving stubble on the soil have had to be learnt, and in turn have kept more water in the soil. Free-market reforms have seen the death of the Australian Wheat Board and the other bodies that governed the production and marketing of agricultural products. Agricultural policy has been at once centralised and fragmented. Farmers have become futures traders, brokers in their own production. Agriculture and food production have been rapidly corporatised, from paddock to supermarket and container ship. In the 201516 Agricultural Census, there were about 86,000 farms in Australia. Ten years ago, there were 135,000.

This speed of change, and the stress and dislocation it causes, is the backdrop to water politics. Throughout the modern history of Australia, the MurrayDarling Basin has challenged our ability to operate as a nation. Now, it may bring politics as normal undone.

Since 2012, the MurrayDarling Basin Plan has sought to claw back the allocation of water to farmers in the area usually described as the food bowl of our nation (although, thanks to the increasing dominance of cotton, these days people prefer to talk of food and fibre). The Basin is Australias most important agricultural region, producing around one-third of the national food supply, and a total of $24 billion in agricultural products. Australia is unusual in the world in that it can more than feed itself producing more agricultural products than we can consume. That is thanks to the Basin. More than 3 million people rely on the river system for their drinking water. If you eat nuts or fruit or bread or meat or rice or vegetables, drink milk or wear cotton, then you are likely tangibly connected to the MurrayDarling.