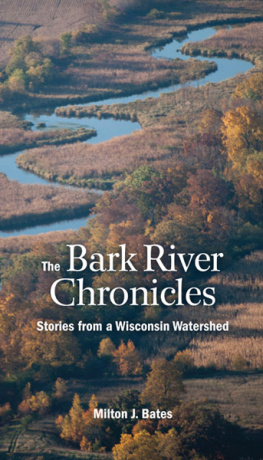

Photo by Elizabeth J. Bates

Milton J. Bates has lived most of his life in Wisconsin. After completing a doctorate in English at the University of CaliforniaBerkeley, he taught at Williams College and Marquette University, retiring in 2010. He has held a Guggenheim Foundation Fellowship and Fulbright lectureships in China and Spain. His previous books include studies of the poet Wallace Stevens and of the Vietnam War. He lives with his wife in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan.

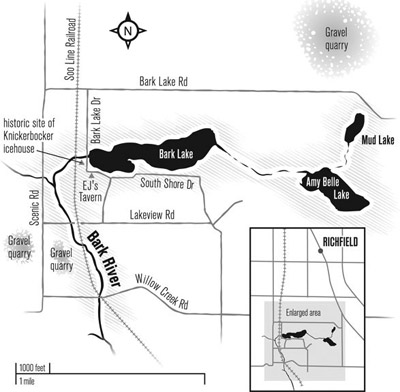

Bark Lake to Willow Creek Road

A green canoe floats, leaflike, on Bark Lake in the town of Richfield, Washington County, Wisconsin. Two figures occupy the boat. Except for the difference in height, they look much the same in their floppy hats and shapeless fleece jackets. An artist would notice how the straw-yellow sunlight of early April picks out a wisp of the womans blonde hair and glances off the mans gray beard. The canoes inverted image wavers slightly on the surface of the water. Overhead, the saturated blue of the sky stretches cloudless to the horizon.

My wife and I have chosen this morning, which happens to be Easter Sunday, as an auspicious moment to begin our voyage of rediscovery on the Bark River. Arriving at the lakeshore, we had gone first to a tavern on its southwest corner. Noticing a man outside, near the entrance, we asked if we could launch our boat at the access across the road, which a hand-lettered sign identified as tavern property. Youre welcome to use it, he offered, adding that this was the only place on the lake where we could put in. He doesnt mind as long as people ask his permission. Well drop in later for a beer, I said. Then we parked at the access and unloaded our gear.

Now we paddle the lake counterclockwise, hugging the shore. A few people are out, working in their yards or simply enjoying the sunshine. A woman sits on her dock with a young girl, possibly her granddaughter. The fish are back, the girl says, sowing the surface of the water with breadcrumbs. Indeed they are, though the fishermen arent, not yet. The only other boat on the lake is a yellow canoe doing the same thing that were doing, but in the opposite direction.

The cottages are mostly small one-story structures on narrow, clutter-friendly lots. There are exceptions, large two- and three-story modern houses set on double lots with manicured lawns and elaborate docks. Here and there are access lots, but they are privately owned and not for use by outsiders. Posted like stern sentinels along South Shore Drive are signs that say no parking, stopping, or standing. In 2007 the township established ownership of two of these boat lots, each twenty feet deep with ten feet of shoreline, and offered them for sale on eBay. The bidding pushed the purchase price up to eight thousand dollars, more than four times the opening figure.

Unruffled by wind, the lake allows us a clear view of its bottom. We glide over silt and marl on the west end, gravel and rock in the midsection, and a spongy accumulation of organic matter on the east shore, bordering a cattail marsh. Numerous painted turtles sun themselves along the marsh, and carp boil away at our approach. A great blue heron flushes from the cattails and flies deeper into the wetland. We discover a narrow creek flowing out of the marsh and follow it upstream, heading east at first, then north. Where the creek exits a grove of trees we notice a low mound of dirt along the bank.

It looks as though someone was trying to dredge or widen the creek, Puck observes. On formal occasions she goes by the name Elizabeth. On canoe outings she favors a nickname borrowed from Shakespeares mischievous sprite in A Midsummer Nights Dream , particularly as the Canadian actress Genevive Bujold interpreted the role in the 1960s.

I consult two maps in a clear plastic holder attached to the rear thwart. The creek appears as a squiggly line on the federal survey map of 1836, I respond. Its still there on our Geological Survey map, but straightened to follow the section line. It extends about a mile due north.

But why the dredging?

Your guess is as good as mine. There are a couple of other man-made channels in the marsh, including one that almost connects Bark Lake with Amy Belle Lake to the east. Both were popular tourist destinations in the late nineteenth century. People could travel by rail from Milwaukee or Waukesha to a platform on the west shore of Bark Lake. Perhaps resort owners dredged the canals for access by steam launch.

The areas lakes and rivers owe their existence to a far more ambitious dredging operation dating to the Ice Age. Though the Laurentide Ice Sheet advanced from the north and retreated many times during the last two million years, todays topography is largely the product of its last campaign, called the Wisconsin Glaciation. One geologist has compared the current landscape to a chalkboard that has been written on and mostly erased many times. Only the most recent markings are clearly legible.

Bark Lake is located just east of the region known as Kettle Moraine, where the markings are especially easy to read. It was here that two lobes of the glacier converged about twenty-four thousand years ago, creating fantastical landforms with equally improbable names: eskers, moulin kames, drumlins, moraines, and kettles. The Green Bay and Lake Michigan Lobes, named for the valleys they followed in their southwesterly advance, covered the land for about ten thousand years, then wasted back (in geologist-speak) to the north. Sediment that had hitchhiked for many miles on the advancing ice took one last giddy ride on its meltwater, washing onto the surface of stranded ice blocks. When the ice melted, the gravel, sand, and silt sank to the bottom of the resulting lake or wetland.

Bark Lake occupies sixty-four acres of a large kettle or basin that was formed in this way. Spreading over several square miles, the basin consists mostly of wetland. Besides Bark Lake, it includes a couple of other depressions where the ice penetrated far enough below the water table to assure a year-round supply of water. These are Amy Belle and Mud Lakes, which cover thirty-three and fourteen acres, respectively. Though the basin has no official geological name, we might call it Glacial Bark Lake, by analogy with more extensive Pleistocene bodies of water such as Glacial Lake Wisconsin in the central part of the state and Glacial Lake Scuppernong in Jefferson and western Waukesha Counties.

Glacial Bark Lake is geologically interesting due to its location at the western edge of the Lake Michigan Lobe and its position with respect to the subcontinental divide that separates the Great Lakes and Mississippi River watersheds. As the Lake Michigan Lobe retreated to the east, following the downward slope of the land, it prevented meltwater from draining in that direction. An ice dam about two miles southwest of todays Bark Lake likewise blocked drainage to the west until the swollen lake breached the dam, discharging a torrent of water, ice, and sediment toward the southwest. This cataclysmic event committed the lake and the Bark River to the Mississippi watershed, with consequences for todays human residents.

After scouring a channel, the great flood subsided into braided meltwater rivers like those in Alaska, flowing southwest toward Glacial Lake Scuppernong. As the Lake Michigan Lobe continued its retreat to the east, the land rebounded from its heavy freight of ice. West of the uplift, deprived of meltwater from both lobes of the diminishing ice sheet, the braided rivers narrowed to the dimensions of todays Bark and Oconomowoc Rivers.