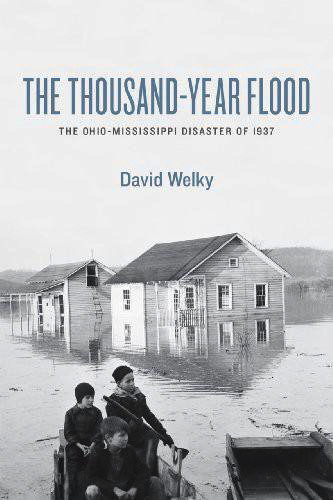

THE THOUSAND-YEAR FLOOD

THE THOUSAND-YEAR FLOOD

THE OHIO-MISSISSIPPI DISASTER OF 1937

DAVID WELKY

The University of Chicago Press

Chicago and London

DAVID WELKY was born and raised in St. Louis, the consummate midwestern river town. He received a BA in history from Truman State University in Missouri and an MA and PhD, both in history, from Purdue University. He has written widely on American culture and society in the interwar era and is the author of Everything Was Better in America: Print Culture in the Great Depression and The Moguls and the Dictators: Hollywood and the Coming of World War II. He is currently associate professor of history at the University of Central Arkansas in Conway, Arkansas, where he lives with his wife and two children.

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2011 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. Published 2011.

Printed in the United States of America

20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN -13: 978-0-226-88716-6 (cloth)

ISBN -10: 0-226-88716-2 (cloth)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Welky, David.

The thousand-year flood : the Ohio-Mississippi disaster of 1937 / David Welky.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN -13: 978-0-226-88716-6 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN -10: 0-226-88716-2 (cloth : alk. paper)

1. FloodsMississippi River ValleyHistory20th century. 2. FloodsOhio River ValleyHistory20th century. 3. Disaster reliefUnited StatesHistory20th century. 4. New Deal, 19331939. 5. United StatesPolitics and government19331945. I. Title.

HV6101937.M57 W45 2011

363.3493097709043dc22

2011014875

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z 39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

To KMW, my own flood baby

Women and children were screamin, sayin, Mama why must we go?

Women and children were screamin, sayin, Lord, where must we go?

The floodwater have broke the levees and we aint safe here no more.

LONNIE JOHNSON , Flood Water Blues (1937)

CONTENTS

PREFACE

WHENEVER I SAID I WAS writing a book about the 1937 flood, people inevitably asked whether I meant the 1927 flood. I assured them that, no, I really meant 1937it was even bigger than the earlier crisis. This comment generally produced a grunt of either incomprehension or suspicion and a quick change of topic because my conversation partners had reached the limit of their knowledge on the subject. They were aware of the great Mississippi River flood of 1927, the subject of a marvelous documentary and several excellent books, but they were certain they had never heard of any flood in 1937. Those who knew me well suspected I was making the whole thing up as a joke at their expense.[]

I have been known to spin a yarn, but to the best of my knowledge I have never fabricated a natural disaster. An enormous flood, the worst river flood in American history, really did paralyze the Ohio valley and much of the lower Mississippi valley in January and February 1937. President Franklin Roosevelt had to shift from celebrating the start of his second term to dispatching tens of thousands of New Deal employees to fight the water. Red Cross executives organized their agencys largest peacetime relief effort to that point in its history. By the time the crest passed, the flood had killed hundreds of people, buried a thousand towns, and left a million people homeless. Some of those communities never came back, at least not in any recognizable form, and all of them were changed.

For all this, the 1937 flood is a catastrophe lost to historians. It merits scant attention in classrooms, textbooks, or even books about the Depression era. My first encounter with the flood was a brief mention, perhaps a sentence, in a survey of the 1930s. It sounded impressive enough that I dropped a mention of it into my PhD dissertation. In retrospect I am baffled that I had never heard of the flood, because much of my personal and professional life has orbited around it. I grew up in St. Louis. With the exception of New Orleans, no city is more closely associated with the Mississippi River basin that encompasses the Ohio. St. Louiss history is to a great extent a story of mans relationship with water. Every time I stood on the river landing I watched a muddy current that was destined to mingle with the Ohio within a day or so. In my life the river was a constant presence, a literal presence. It was something to drive across, a backdrop for television commercials, the setting for occasional visits to the old Goldenrod Showboat. Like my heartbeat, the river was rarely contemplated yet always there.

My adult years kept me circling around the flood. I became a historian of the 1930s, a decade replete with both natural and manmade disasters. During a visit to Pittsburgh I stood atop Mount Washington to watch the Ohios ongoing birth and rebirth at the junction of the Allegheny and the Monongahela. Watching this triple union, I laughed to realize that every drop of the water enjoyed one shining instant as the leading edge of the Ohio River. Later I moved to Arkansas, site of some of the worst moments in the floods early days. Trips to see my family took me through Arkansass old sharecropper regiona district that in 1937 swarmed with flood victims seeking safetythen carried me into the Missouri bootheel, another scene of great suffering. From there the highway passes just west of the setback levees of the Birds Point spillway, a structure that will play an important part in the following pages. Finally, I made several visits to Memphis, where I navigated streets that once echoed with footsteps from tens of thousands of refugees. All this time I knew nothing of the flood, and I had no idea that life was familiarizing me with places destined to carry great personal significance.

One day I noticed that casual reference to a 1937 flood I had made years earlier. Resolving to learn something of this catastrophe, I soon discovered that apart from a handful of quickie recaps appearing a few months after the crest, no one had written a book about it. And from that realization came this work.[]

This project took me all over the eastern half of the United States. It gave me an opportunity to revisit familiar archives, investigate cities I had never seen, and explore towns I had never heard of before I delved into my research. I learned in Cairo, Paducah, Shawneetown, and the other places my journey led me that the people of the Ohio valley were eager to discuss the floodit was not so much a lost disaster as one that has gone into hiding. Its still there if you know where to look for it. It seemed that everyone I met had a story to share once they established that I was interested in 1937, not 1927. They convinced me that the flood never really passed to the sea. Today it rolls down the valley as a torrent of memories, some of them firsthand and others passed from generation to generation like prized heirlooms.

These stories touch on a few consistent themes. Many people express amazement that they or their ancestors had endured a calamity of such inconceivable magnitude. Survivors of the disaster remember it with crystal clarity twenty, fifty, sixty years later. Their descendants exhibit profound respect for the sacrifices their parents or grandparents made during the wet, frigid weeks of early 1937. Such admiration suggests that those people were somehow different from us, that the Americans of 1937 were better equipped to handle a crisis. This implies that a social decline has occurred over the past seventy-five years, that present-day Americans are too weak, ineffectual, or pampered to fight a rising river, run from their homes, or rebuild cities. It reflects a longing for a simpler time when neighbors cared for each other and communities stuck together.