River, Reaper, Rail

SERIES ON OHIO HISTORY AND CULTURE

Series on Ohio History and Culture

Kevin Kern, Editor

Joyce Dyer, Gum-Dipped: A Daughter Remembers Rubber Town

Melanie Payne, Champions, Cheaters, and Childhood Dreams: Memories of the Soap Box Derby

John Flower, Downstairs, Upstairs: The Changed Spirit and Face of College Life in America

Wayne Embry and Mary Schmitt Boyer, The Inside Game: Race, Power, and Politics in the NBA

Robin Yocum, Dead Before Deadline: And Other Tales from the Police Beat

A. Martin Byers, The Ohio Hopewell Episode: Paradigm Lost and Paradigm Gained

Edward C. Arn, edited by Jerome Mushkat, Arns War: Memoirs of a World War II Infantryman, 19401946

Brian Bruce, Thomas Boyd: Lost Author of the Lost Generation

Kathleen Endres, Akrons Better Half: Womens Clubs and the Humanization of a City, 18251925

Russ Musarra and Chuck Ayers, Walks Around Akron: Rediscovering a City in Transition

Heinz Poll, edited by Barbara Schubert, A Time to Dance: The Life of Heinz Poll

Mark D. Bowles, Chains of Opportunity: The University of Akron and the Emergence of the Polymer Age, 19092007

Russ Vernon, West Point Market Cookbook

Stan Purdum, Pedaling to Lunch: Bike Rides and Bites in Northeastern Ohio

Joyce Dyer, Goosetown: Reconstructing an Akron Neighborhood

Robert J. Roman, Ohio State Football: The Forgotten Dawn

Timothy H. H. Thoresen, River, Reaper, Rail: Agriculture and Identity in Ohios Mad River Valley, 17951885

Titles published since 2003.

For a complete listing of titles published in the series,

go to www.uakron.edu/uapress.

River, Reaper, Rail

AGRICULTURE AND IDENTITY IN

OHIOS MAD RIVER VALLEY, 17951885

Timothy H. H. Thoresen

Copyright 2018 by Timothy H. H. Thoresen

All rights reserved First Edition 2018 Manufactured in the United States of America.

All inquiries and permission requests should be addressed to the Publisher,

The University of Akron Press, Akron, Ohio 44325-1703.

ISBN: 978-1-629220-76-5 (paper)

ISBN: 978-1-629220-77-2 (ePDF)

ISBN: 978-1-629220-78-9 (ePub)

A catalog record for this title is available from the Library of Congress.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

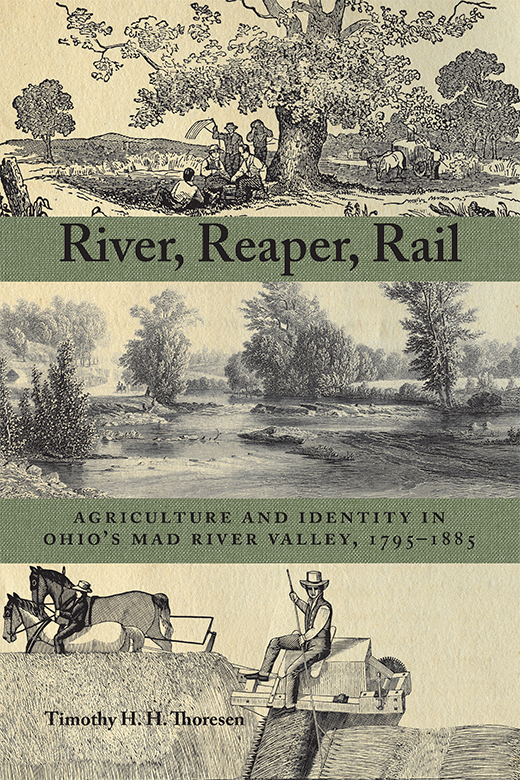

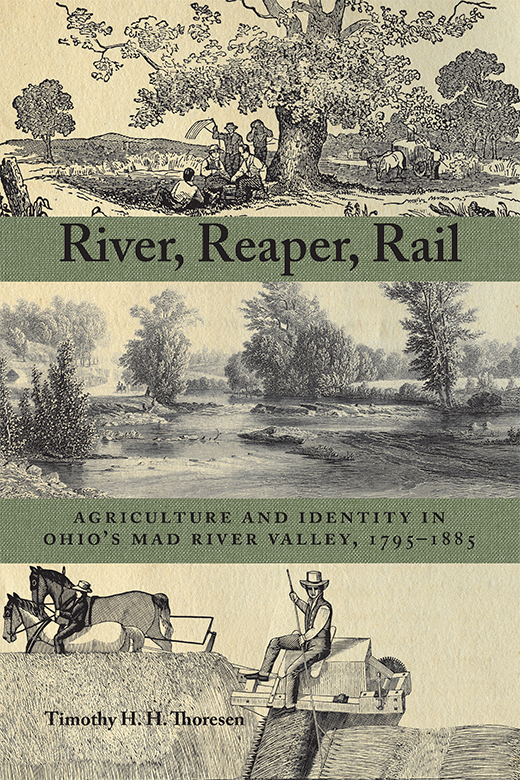

Cover: (Top) The Harvesters Discussing the Temperance Lecture, reprinted from A Son of Temperance, Thrilling Scenes in Cottage Life (Hartford: Case, Tiffany, and Co., 1855), p 379; (middle) Mad River, Near Springfield, O., reprinted from Rev. B. F. Tefft, ed., The LadiesRepository (Cincinnati, 1851), facing p. 321; (bottom) 1851 advertising broadside for Husseys Reaping Machines, courtesy of the Ohio History Connection. Cover design by Amy Freels.

River, Reaper, Rail was designed and typeset in Adobe Caslon by Amy Freels and printed on sixty-pound natural and bound by Bookmasters of Ashland, Ohio.

For my daughtersSaraLynne, Ahna, Karis

Contents

This study has its origin in an invitation to participate in the 2005 Champaign County Bi-Centennial lecture series sponsored jointly by the Countys Bi-Centennial Commission and Urbana University. While the original lecture gave focus to a personal interest in farm machines and agricultural technology, it was also the stimulus to look at a field of scholarship I had previously barely known. A decade-long project evolved. Loosely an exploration of systemic change in agriculture, the work was from its inception distracted by the personal elementsthe lives and stories of the people who experienced the change. I found myself looking for the narratives, the representative and illustrative stories that made sense of the patterns I was seeing. My principal models come from ethnography, my language often draws on economics, and my perspective is always historical.

The initial sources for this project were the commonly available publications in the history of agriculture, selected manuscript schedules and summary statistics of the Census Bureau for the period under review, and the Annual Report of the Ohio State Board of Agriculture from its beginning in 1846. Champaign County residents of the 1800s may have kept account books, and a few kept diaries. None of those documents has survived unless they are still hidden away in attic boxes or bottom drawers. A few private letters survived in published form when they were included in pioneer reminiscences following the Civil War. Otherwise, my principal and quite rich primary source has been the weekly Urbana newspapers. The earliest, The Farmers Watch Tower, first appeared in 1812, and only a few issues survive. From 1821 and the appearance of Ways of the World, a weekly newspaper in Urbana was fitfully regular. Names changed, as did the proprietors (their word for the owner/publisher/editor). Long-term stability was achieved in 1849 with the Urbana Citizen and Gazette which ran continuously for forty years until displaced by the Urbana Daily Citizen. The Citizen was proudly Whig, then Republican, and was challenged for readership by much less successful Democratic papers. Offsetting its political bias was its self-conscious role as the principal newspaper in the county. Beyond matters of public notice and legal record, the Citizen generously provided space for reader comment, letters from the war front or from the West, and reminiscences of ye olde days. Mixed in on the same unnumbered folio pages were paid advertisements for professional services, retail dry goods, and agricultural implements, allowing the historian a complementary insight into local events and public transactions. Less consistently I also consulted the much more limited surviving files of the other newspapers attempted in the countys several smaller towns. These source materials were encouragingly made available to me by the staffs of the Champaign County Public Library, the Champaign County Historical Society, the Urbana University Library, the Wright State University Library, and the archives of the Ohio History Connection.

The story of Champaign County and its Mad River Valley is a story of the Ohio country and, with reference to agriculture, it is a story of America and its rural heartland. It is the story of land-hungry migrants carrying a market-oriented farm ethos across the Appalachians into the Ohio Valley and displacing the native inhabitants. As the migrants adapted their traditional farming practices to the local conditions, practice was also affected by changes in farming technology, changes in modes of transport and communication, changes in market orientation, and perhaps most obviously into our own day, changes in a dynamic and global industrial economy. For a few brief decades in the middle of the nineteenth century, Champaign County was very near the center of the nation demographically, agriculturally, and industrially. Its people looked optimistically in all directions, stirred especially by big changes in the transportation infrastructure, the mechanization of the harvesting process, and the character of state-sponsored farmer organizations. Driven by dynamics from outside the county, the effect of those developments on life inside the county was intense because of the timing. And yet, through all those changes we should see that the individual farmer, like the evolutionary process itself, has been fundamentally conservative. Change is endured to preserve what otherwise would be at risk. Everything is interrelated. Better yields, higher prices, less work, lower costs are all values within a complex, a network, a system, a culture which understands that change in one place will certainly have unanticipated implications and change in other places. For the farmer, improvement is therefore tested against multiple annual cycles of planting and harvest before it is judged a success, and outsiders, experts, and city folk just dont know. But change did happen, and therein is our story. It begins with the land itself.