Slaverys Borderland

EARLY AMERICAN STUDIES

Series editors:

Daniel K. Richter, Kathleen M. Brown,

Max Cavitch, and David Waldstreicher

Exploring neglected aspects of our colonial, revolutionary, and early national history and culture, Early American Studies reinterprets familiar themes and events in fresh ways. Interdisciplinary in character, and with a special emphasis on the period from about 1600 to 1850, the series is published in partnership with the McNeil Center for Early American Studies.

A complete list of books in the series is available from the publisher.

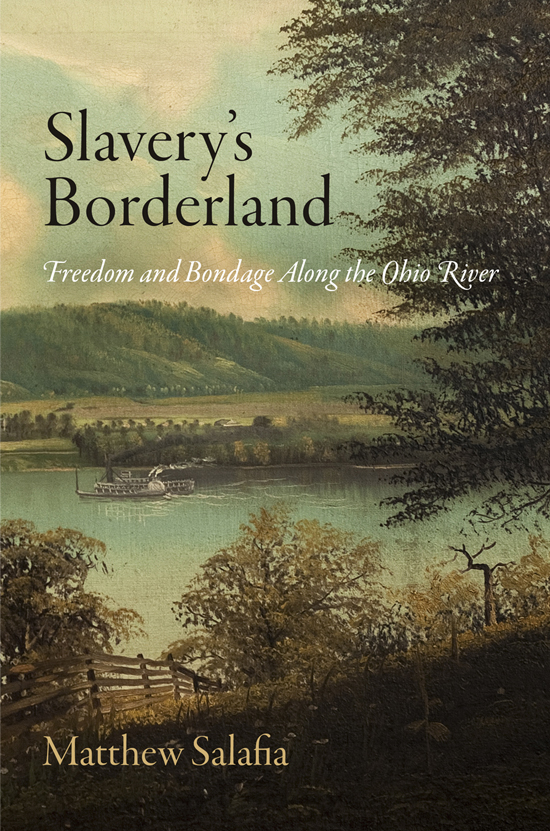

SLAVERYS BORDERLAND

Freedom and Bondage along the Ohio River

MATTHEW SALAFIA

Copyright 2013 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used for purposes of review or scholarly citation, none of this book may be reproduced in any form by any means without written permission from the publisher.

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112

www.upenn.edu/pennpress

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Salafia, Matthew.

Slaverys borderland : freedom and bondage along the Ohio River /

Matthew Salafia. 1st ed.

p. cm. (Early American studies)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8122-4521-9 (hardcover : alk. paper)

1. SlaveryKentucky. 2. SlaveryIndiana. 3. SlaveryOhio.

4. Ohio River ValleyHistory18th century. 5. Ohio River Valley

History19th century. I. Title. II. Series: Early American studies.

E445.K5S25 2013

306.3620977dc23

2012049856

To Beth

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Listening to the River

In Uncle Toms Cabin, Eliza Harris clasped her child as she darted toward the rivers edge. Then with one wild cry and flying leap, she vaulted sheer over the turbid current by the shore on to the raft of ice beyond she leaped to another and another; stumbling, leaping, slipping, springing upwards again. She saw nothing, felt nothing, till dimly, as in a dream, she saw the Ohio side, and a man helping her up the bank. Eliza risking her life to cross the Ohio River personified the sentiment liberty or death. On the southern bank slave catchers tried to pull Eliza back to slavery; on the northern bank someone helped her toward freedom. However, without the ice sheets the Ohio River would have been impassable. Eliza leaped across a solid, albeit unstable, divide between slavery and freedom.

Yet Harriet Beecher Stowes border was fleeting because Eliza leaped across chunks of ice that disappeared from under her feet. Indeed outside of fiction the Ohio River remained an unstable divide between slavery and freedom throughout the antebellum period. In 1787 the Northwest Ordinance made the Ohio River the dividing line between slavery and freedom in the West; yet when the Civil War broke the country in two in 1861, this region failed to split at this seam. This book traces the history of the Ohio River borderland from its natural and human origins, through its political definition in the early republic, to maturation during the antebellum period, and to its surprising resilience during the sectional crisis. As residents on both sides of the river struggled to accommodate it as at once a dividing line and a unifying economic force, they defined this borderland by its inherent contradictions. Rather than marking a line that slavery could not penetrate, the Ohio River muddied distinctions, and residents used that ambiguity to try to hold the region together even against the threat of civil war.

* * *

The Ohio River Valley was a peculiar place in antebellum America. North of the Ohio River, southern migration and economic connections with the southern economy gave the region a southern bent, and cultural historians often put the cultural division between North and South somewhere north of the Ohio River. Historians of slavery have demonstrated that slavery at the top of the South was different from that of the Deep South. As a result white Kentuckians lukewarm commitment to the institution became a source of conflict with their more southerly neighbors. In 1861 as northerners and southerners alike geared for war, Kentuckians refused to secede and actually declared their neutrality. In this book these stories are brought together to demonstrate that while the lower North was uniquely southern and the upper South was uniquely northern, the result was a region defined by its blend of influences.

So that the peculiarities of this region can be understood, this study historicizes the border itself. Placing the areas north and south along the river at the center of the interpretation contributes to a new history of the Ohio River Valley that looks for regional coherence across state borders. Historians, political scientists, and cultural and literary critics have argued that where geographical borders fail to contain and define human interactions, residents create a unique third country in between called borderlands. Out of their interactions, residents of these borderlands create regions defined by their hybridity. Studies have demonstrated that borderlands are complicated zones of cultural and physical confrontation and accommodation where interactions shape policies. When national leaders made the Ohio River the boundary between slavery and freedom, they reshaped residents movements and interactions in the region. The movements encouraged by this river border informed local residents understanding of the region and their place in it. Movement was normative in the Ohio River Valley, and as a result it was a place where dichotomies could not apply; instead residents defined the region as a borderland.

In most historical treatments, the rise of the new American nation was the beginning of the end for the Ohio River Valley borderland. But historians base this argument on a historically specific definition that ties the borderland to the colonial period. By this definition, borderlands were the contested boundaries between colonial domains, and the creation of nationally recognized state borders turned borderlands into bordered

I have tried to follow the contours of residents mental mapping of the region. I have not made the history of this region fit my model of a borderland; quite to the contrary, this region was a borderland because residents defined it that way. When first created in 1787, the northern and southern limits of this borderland extended into the interiors of the states. Over the course of the antebellum period, economic and social changes shrank the borderland to the counties that bordered the Ohio River, because those who lived along the river continued to define themselves by their relationship to this border. While they may not have seen themselves as very different in 1800, by 1861 Ohioans and Indianans believed that they were quite different from their slaveholding neighbors in Kentucky. If they imagined themselves as different from one another, borderlanders also defined their region as unique from the rest of the country. By the 1850s sectional conflict pushed northerners and southerners apart, but residents of the Ohio River borderland denounced sectionalism on both sides and emphasized their own ability to coexist across a divisive border. This was not a region without conflict, but residents never gave up on the idea of living half slave and half free. It was a place where confrontation coexisted with accommodation, and where disunity highlighted similarities. This simultaneous existence of contradictory impulses characterized the Ohio River borderland.