IMAGES

of America

THE 1964 FLOOD OF

HUMBOLDT AND

DEL NORTE

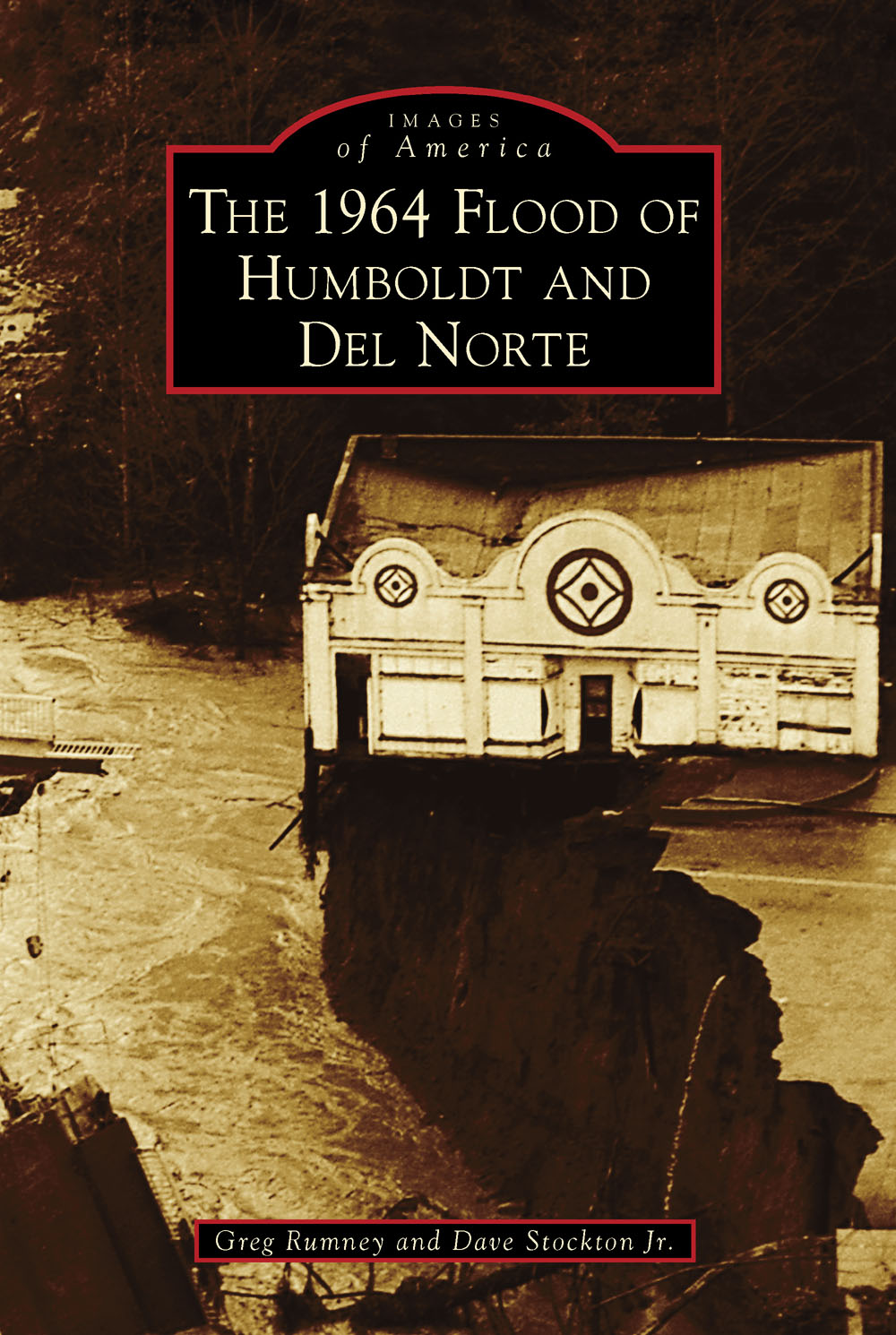

ON THE COVER: Hanging on perilously, this storefront was no match for the surging floodwaters of the Eel River. The river destroyed numerous bridges and roadways and cut off the towns along the river from aid for days. This store eventually lost its fight with gravity and plunged into the raging river below.

IMAGES

of America

THE 1964 FLOOD OF

HUMBOLDT AND

DEL NORTE

Greg Rumney and Dave Stockton Jr.

Copyright 2014 by Greg Rumney and Dave Stockton Jr.

ISBN 978-1-4671-3088-2

Ebook ISBN 9781439644591

Published by Arcadia Publishing

Charleston, South Carolina

Library of Congress Control Number: 2013910001

For all general information, please contact Arcadia Publishing:

Telephone 843-853-2070

Fax 843-853-0044

E-mail

For customer service and orders:

Toll-Free 1-888-313-2665

Visit us on the Internet at www.arcadiapublishing.com

To my wife, Penny

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This book would not have been possible without the stories and pictures of those who experienced this flood firsthand. Rudy Gillard started his photographic career in the late 1940s after he and his wife, Jenny, moved to Fortuna from the Oakland area. He set up shop, doing portraits and other work, on Main Street in Fortuna. In 1964, Rudy became the official photographer to document the devastating and unprecedented Christmas flood of 1964. When Rudy was about to retire, he donated all his negatives to Greg Rumney to insure the preservation of the past would be carried on. This donation included several thousand negatives and images of the Christmas flood of 1964. This book presents a small sample of some of his best images. Rudy passed away in 2009.

We would also like to thank Ray Evans, the late Robert Childs, Charley and Betty Thomas, and David Carneggie for not only sharing photographs but also firsthand experiences of the flood and its aftermath. We are also indebted to Susan OHara for some duplicates from the Humboldt Redwoods State Park book. The full story of the flood could not be told without these important photographs. Humboldt Redwoods Interpretive Association has helped with information and excerpts from The Killer Eel, a 32-page magazine published in 1965. The Fortuna Depot Museum has also assisted with the text. A special thanks goes to Penny Rumney for all her hard work from the beginning, scanning and organizing the overall project. A story of this size and impact cannot be completely told from these pictures, but those that have been contributed will give the reader a good feel of the event. All images appear courtesy of Rudy Gillard.

INTRODUCTION

The 1964 flood was one of those perfect storms. All the weather events lined up in a sequence that maximized the runoff of rivers and streams over five states. Northern California and Southern Oregon were the hardest hit and were directly in the path of the brunt of the storms. There were three main components to this perfect storm, and these three focused on the 3,684-square-mile drainage of the Eel River and its tributaries along with the 15,751-square-mile Klamath River drainage. The first part of the storm began around December 13, 1964, with a cold front from the north moving in and dropping a few feet of snow. After this storm was spent, a warm storm from the south, locally called the pineapple connection, moved in and dropped 22 to 37 inches of rain in three days and over 30 for the week. The volume was so intense that drivers who turned their windshield wipers on high speed still could not keep the water off long enough to see. As if this were not enough, the third component of this perfect storm was the highest tide of the year that came during the peak hours of the flood crest. This caused a damming effect on some of the bridges that raised water levels to record highs. Locals believed that the Eel River would drop for at least eight hoursno matter the weather conditions as soon as it crested; however, this time, the Eel River stayed at a near maximum for almost 24 hours, an unheard-of event on the Eel River drainage.

Residents along the Eel River were no strangers to high waters and floods. A tried-and-true method employed by the old-timers to check water levels was to drive a stake at the waters edge and come back in a half hour. This would enable the resident to calculate the waters increase per hour and, coupled with the weather forecast or a reported crest from the south drainage, a rough estimate of how high the river would rise. At the time of the flood, there was also the mind-set that the Eel and Klamath Rivers could get no higher because many experts had said that the 1955 flood was the 1,000-year flood. The locals soon realized that the rate of rise was double that of 1955, and from there, with the rain as intense as it was, there was no telling how high both rivers could go. Ferndale and Fernbridge were both hit hard. Fernbridge, with it businesses, such as the Challenge Creamery and Barnes Tractor, all next to the main Eel River, and Ferndale, with its dairy herds and barns, were victims not only to the water, but also piles of logs from the lumber operations upstream. Both were so close to the mouth of the river that drift was caught almost anyplace with a natural barrier. One happy story that came out of Ferndale was that a cow with her herd number tag came into the harbor at Crescent City, about 300 miles north, three days after the peak of the flood. The cow was fine but very hungry. In a few weeks, she was returned to her herd in Ferndale. There were several veterans of the 1937 flood and a few from the 1915 flood, and all were unanimous that 1964 flood was far worse than any deluge they had seen. Both the 1915 and 1937 floods left remnants behind to build on, and residents took it in stride. The 1955 flood saw the loss of two communities, Dyerville and Elinor. These losses were of great consequence and were as much of a moral blow as a physical one. These destructive floods, however, would pale in comparison to the great Christmas flood of 1964.

In anticipation of floodwaters, the towns along the Eel River, such as Loleta, Ferndale, Fernbridge, Lower Fortuna, Alton, Metropolitan, Rio Dell, Scotia, Pepperwood, Shively, Holmes, Larabee, South Fork, Weott, Myers Flat, Phillipsville, and Sylvandale, started evacuating days before the initial storm. Businesses moved their inventories to high ground as some private homes were also emptied of what could be carried. In many cases, people living where the rivers had never been before took what they could and moved to higher ground. Most, when their items were safe, returned to help neighbors. Those with the mind-set that the flood of 1955 was the worst possible hung on until it was obvious this flood was beyond what anyone had seen. A strange phenomenon reported by residents was a deep, unsettling roar when the river was extremely high; the sound was similar to that of a strong earthquakea haunting sound of out-of-control violence.

Food and shelter were immediate issues following the flood. People with freezers or any food storage device opened them up to the community to feed all that were hungry. Residents whose homes survived the flood provided shelter until disaster relief came. Many remarked it was a shame it took a disaster of this scale to bring people together to share all they had. There was a great sense of community for several months following.

People along the rivers had experienced disasters before and prepared town centers for food and other necessities to be shared. Security and communication systems were set up to the outside world to restore as much semblance of normalcy as possible. Along both rivers, what could be saved or salvaged was done as much as possible. Many people recognized possessions downstream that belonged to their neighbors, and these items were returned.

Next page