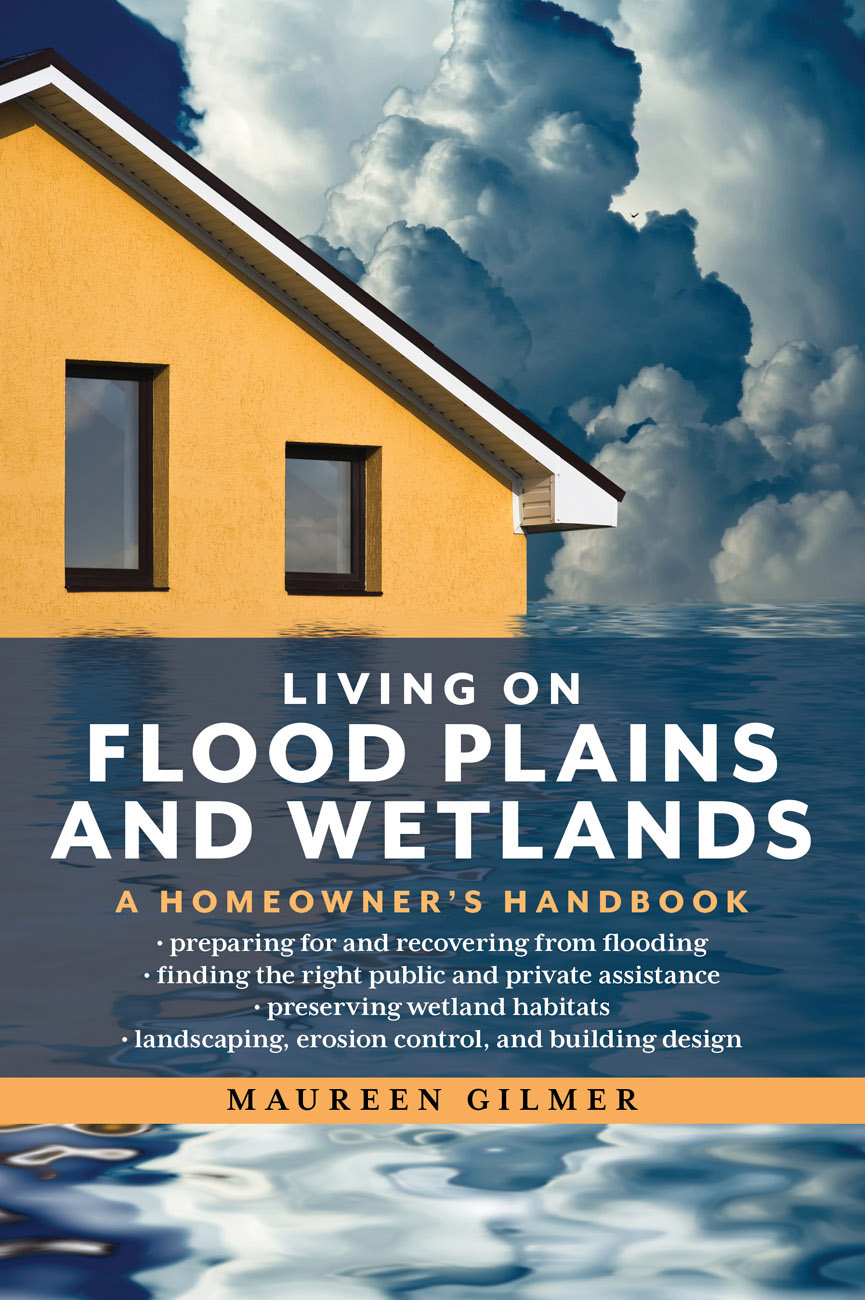

ALSO BY MAUREEN GILMER:

The Colorful Dry Garden

Growing Vegetables in Drought, Desert and Dry Times

Palm Springs-Style Gardening

The Small Budget Gardener

Gaining Ground

The Gardeners Way

Water Works

Rooted In The Spirit

God In The Garden

Redwoods and Roses

The Complete Idiots Guide To A Beautiful Lawn

Easy Lawn and Garden Care

The Complete Guide to Southern California Gardening

The Complete Guide to Northern California Gardening

California Wildfire Landscaping

The Wildfire Survival Guide

An imprint of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Blvd., Ste. 200

Lanham, MD 20706

www.rowman.com

Distributed by NATIONAL BOOK NETWORK

Copyright 1995 by Maureen Gilmer

This Lyons Press edition 2019

All photos and illustrations by the author unless otherwise noted.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available

ISBN 978-1-4930-3834-3 (paperback)

ISBN 978-1-4930-3835-0 (e-book)

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Printed in the United States of America

INTRODUCTION

Water is unquestionably one of the vital keys to our future security and survival, as well as our well-being. If this nation is to end the waste of our water resources, if we are to develop more fully the use of our water for economic growth and the needs of our exploding population, we should-without further delay-greatly accelerate our programs as regards conservation, transportation, power, flood control, and other aspects of our natural water resources.

JOHN F. KENNEDY

T he story of our American waterways begins hundreds of years ago, when pioneers wandered through a virgin land where nature reigned supreme. Tiny, fledgling populations could do little more than simply flee to high ground when tempestuous waters periodically inundated towns and farms. Over time the cities grew up; new concerns such as improved navigation, increased commerce, water resource development, and, perhaps best known of all, human safety guided the hands of governments.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers took on the task of organizing waterway improvement projects on a national basis in order to attain the modern goals of navigation and flood control. Among its greatest achievements were hydroelectric dams, flood control facilities, bridges, vast levee systems, and many other mechanical means of controlling rivers and coastal waterways. But despite its best efforts, disastrous flooding continued as development encroached onto the flood plain and sometimes into the floodway itself.

By the 1960s a broader approach to flood control was implemented, using land use regulation, better flood forecasting, federal flood insurance, and even relocating property out of the floodway to reduce damage. The Corps set its efforts to developing flood data for entire watersheds and river basins in order to determine suitable land uses that would not increase the flooding potential. It was indeed a time of transition.

During the environmental decade of the 1970s, new laws concerning plants and wildlife brought an added dimension to the Corpss responsibilities. This was no easy matter because the Corps was staffed with civil engineers trained in large-scale, mechanical flood control methods. Yet they were now charged with issues of pollution, watershed management, status of wetlands in their myriad forms, and care of groundwater aquifers. Many of the engineers found it difficult to make the transition and to learn new ways of working with other professions concerned with environmental quality.

As the progressive 1980s arrived, the emphasis was on coastal conditions, where development was actively curtailed by regulatory agencies concerned by offshore drilling, dune destabilization, and displacement of coastal habitat by homes and commercial waterfront marinas. The Corps and other agencies continued to evolve from problem solving to regulatory enforcement of the tremendous number of new federal programs controlling the use of waterways and flood plains. The following are only some of the many examples of legislation that went into effect between 1960 and 1990. They illustrate just how massive a web of regulations the Corps must contend with and how challenging its task will be in years to come.

Housing Act of 1961

Land and Water Conservation Fund Act, 1964

National Flood Insurance Act, 1968

National Environmental Policy Act, 1969

Coastal Zone Management Act, 1972

Clean Water Act of 1972

National Dam Inspection Act of 1972

Endangered Species Act of 1973

Flood Disaster Protection Act of 1973

Disaster Relief Act of 1974

Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976

Housing and Community Development Act of 1977

Coastal Barrier Resources Act, 1982

Dam Safety Act, 1986

Emergency Wetlands Resources Act of 1986

Water Resources Development Act, 1986

Housing and Urban Development Act of 1987

Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Amendments of 1988

Executive Order 11990, Protection of Wetlands

Water Resources Development Act of 1990

Combined with new regulations concerning environmental issues of the 1990s, such as new clean water legislation, it is clear that there are big changes in the roll of the Corps of Engineers. Similar changes have also come about in the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, which is heavily involved with wetland identification on private agricultural lands. Yet despite the increased responsibility, these agencies are suffering from declining budgets and limited staff.

We must all understand that the new century will bring many changes and much frustration all around as we seek to balance the needs of individual citizens with those of the environment and our economy. Many debatable theories of emerging environmental science are today being accepted as law, which becomes dangerous when they are the basis for regulating property owners rights and land use. In our zealous effort to protect the ecology, it is easy to make mistakes that can have far-reaching consequences into the future. And in the long run, it is the survival of the family as a viable economic unit that determines whether we will continue to grow and prosper as a nation.

This book was written to give people the tools they need to deal with flooding and the potential for more frequent flooding in the future. It also attempts to show how Americas goals are changing and that few issues are as cut-and-dried as they used to be. Some issues of the environment are of true concern, but they can also become political tools rife with hidden agendas and power plays. Only in the midst of disasters such as the flooding of the Mississippi, the recent high water of the southeastern states, and the flooding in Houston, Texas, do the truths come to light. It is clear that above all, floods kill people, and there is nothing more important to Americans living in and among our wetlands and flood plains.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.