Table of Contents

A PLUME BOOK A WELL-PAID SLAVE

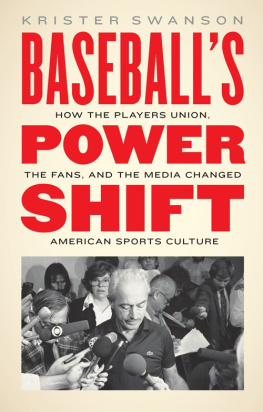

BRAD SNYDERs previous book, Beyond the Shadow of the Senators, won the Robert Peterson Recognition Award from the Society of American Baseball Research (SABR) and was named one of Booklists Top Ten African American Nonfiction Titles of 2003. Both Beyond the Shadow of the Senators and A Well-Paid Slave were finalists for SABRs Seymour Medal, Spitball magazines Casey Award, and Elysian Fields Quarterlys Dave Moore Award. A graduate of Duke University and Yale Law School, Snyder has written for numerous publications, including the Baltimore Sun, the Washington Post, the St. Petersburg Times, and the Yale Law Journal. He is a lawyer and a full-time writer living in Washington, D.C. Visit www.wellpaidslave.com.

Praise forA Well-Paid Slave The Washington Post Best Non-Fiction Books of 2006 Selection The New York Times Book Review Editors Choice

Much as Flood sacrificed money for principle, Snyder left a legal career to undertake this project without a publisher. Anyone with a sociological interest in American sport should be glad he did. Writing with dispatch and grace, he places Floods challenge to baseball squarely where it belongs, as the final radical act of the 1960s civil rights movement. The Washington Post

In A Well-Paid Slave, Brad Snyder weaves together a sympathetic biography of Flood and a lucid, meticulously detailed analysis of his lawsuit.

The Baltimore Sun

A Well-Paid Slave is... a deeply researched and revealing portrait of Flood the man.... Further studies of Flood and his legacy may come along, but this one will very likely stand as definitive, the standard against which others must be measured. Snyder has wrought something worthy of the daunting convolution of his subject matter. Vastly more substantial than ordinary jock fare, this book should appeal to the serious reader of legal and/or general American history who has little knowledge or interest in baseball per se. Its that good.

The Hardball Times

An extraordinarily rich tale of a conflicted man who made a difference in the world. Flood is the man who took on the baseball structure and shook it to its core. He did for ballplayers economic rights what Jackie Robinson did for their human rights. Ventura County Star

Why would a man give away a career that is the dream of millions of men? To change the game that he loved. Brad Snyder shows how and why Curt Flood had a greater impact on baseball than any other player of our time. Its a wonderful tale. Richard Ben Cramer, author of Joe DiMaggio

ALSO BY BRAD SNYDER

Beyond the Shadow of the Senators: The Untold Story of the Homestead Grays and the Integration of Baseball

To John Thompson and Ray Gavins

CHAPTER ONE

The phone in Curt Floods 19th-floor apartment rang at 4 a.m. on October 8, 1969. A sportswriter broke the news to him. A few hours later, another phone call made it official. The second conversation lasted no more than two minutes. The voice on the other end of the phone was so emotionless that it sounded almost like a prerecorded message.

Hello, Curt?

Yes.

Jim Toomey, Curt. Curt, youve been traded to Philadelphia. You, McCarver, Hoerner, and Byron Browne. For Richie Allen, Cookie Rojas, and Jerry Johnson. Good luck, Curt.

Thanks. Thanks a lot.

Flood was polite but thought he deserved better. After 12 seasons of playing center field for the St. Louis Cardinals, he did not find out about the trade from the teams owner or general manager. He heard about it from a sportswriter and then from Toomey, a man Flood later described as a middle-echelon coffee drinker from the front office. This was no way to treat Floodthe teams co-captain, a three-time All-Star, a seven-time Gold Glove winner, and a major cog in the Cardinals World Series teams of 1964, 1967, and 1968.

It struck Flood as unfair that, like every professional baseball player at that time, he had no right to sign with another team or to test his value on the open market. In 1969, free agency was a foreign concept. The Cardinals could ship him off to Philadelphia because players belonged to their teams for life.

For 90 years, baseball players had been bought, sold, and traded like property. In 1879, the eight National League teams agreed to allow each team to reserve five players. This agreement forbade other National League teams from signing the reserved players and therefore prevented those players from changing teams based on their own free will. By the time the National League made peace with the upstart American League in 1903, reserving players was standard practice. Under the major league rules in 1969, each team reserved 40 players (25 on the major league roster plus 15 minor leaguers), all of whom were unable to sign with other teams.

The owners foisted the reserve system on the players by including in the standard player contract a provision referred to as the reserve clause. Paragraph 10(a) of the Uniform Player Contract said, [T]he Club shall have the right... to renew this contract for a period of one year. Under this clause, a team could automatically renew a players contract for another season at as little as 80 percent of the previous seasons salary. Read literally, the Uniform Player Contract was a one-year agreement plus a one-year option on a players services. But the players knew that they were not free to negotiate with other teams and their salaries could automatically be reduced by 20 percent for the following year. Before each season, therefore, they had no choice but to accept their teams final salary offers and to sign new contracts containing the same one-year option provision. A contract for one year became, in effect, a contract for life.

Floods trade from St. Louis to Philadelphia reawakened latent feelings of unfairness about the reserve system. His eventual decision to act on those feelings led to the first in a series of fights for free agency that altered the landscape of professional sports. Like his hero, Jackie Robinson, Flood had the courage to take on the baseball establishment. In 1947, Robinson started a racial revolution in sports by joining the Brooklyn Dodgers as the 20th centurys first African-American major leaguer. Nearly 25 years later, Flood started an economic revolution by refusing to join the Philadelphia Phillies. The 31-year-old Flood sacrificed his own career to change the system and to benefit future generations of professional athletes. Todays athletes have some control over where they play in part because in 1969 Flood refused to continue being treated like hired help. But while Robinsons jersey has been retired in every major league ballpark, few current players today know the name Curt Flood, and even fewer know about the sacrifices he made for them.

The morning of Toomeys phone call, Flood woke up his two roommateshis oldest brother, Herman, and his friend and business manager, Marian Jorgensenand swore to them that he was not going to Philadelphia. Like most proud ballplayers traded at the height of their careers, he threatened to retire.

Flood, however, was not like most ballplayers. He would joke around with his teammates one minute and stick his head in a book the next. He spoke in a soft, soothing voice and sounded like a college professor. He liked to draw, played classical piano by ear, and taught his best friend and road roommate, pitcher Bob Gibson, how to play the ukulele. Both Gibson and former Cardinals first baseman Bill White, Floods closest friends in baseball, had attended college. Flood, however, had missed out on the college experience and engaged in constant self-education. When Bob and I were reading the