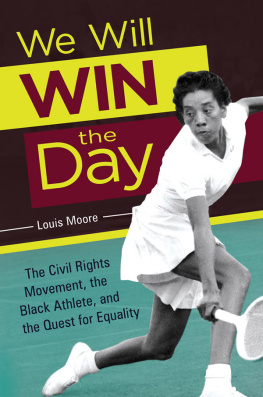

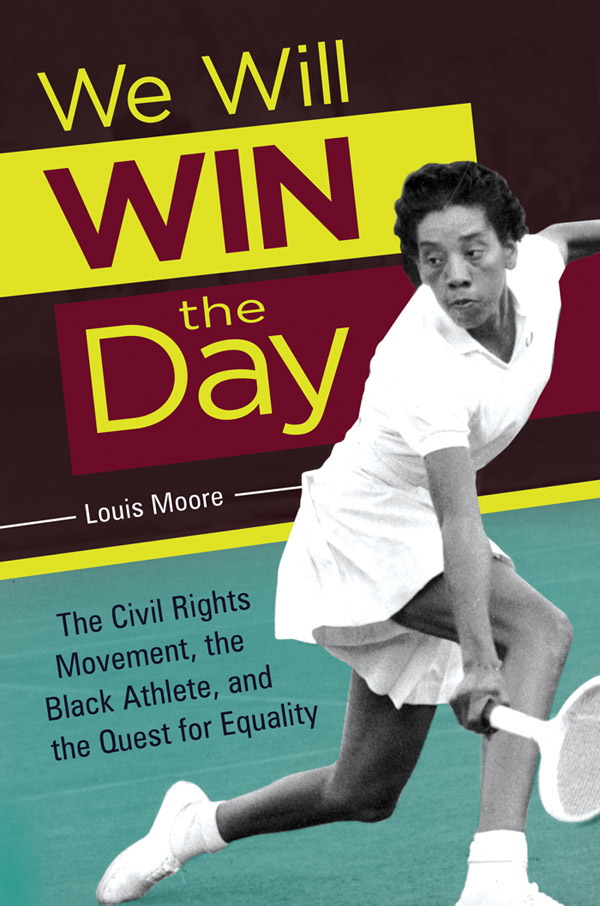

We Will Win the Day

We Will Win the Day

The Civil Rights Movement, the Black Athlete, and the Quest for Equality

Louis Moore

Copyright 2017 by Louis Moore

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Moore, Louis, 1978 author.

Title: We will win the day : the Civil Rights Movement, the Black athlete, and the quest for equality / Louis Moore.

Description: Santa Barbara, California : Praeger, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017019469 (print) | LCCN 2017023062 (ebook) | ISBN 9781440839535 (ebook) | ISBN 9781440839528 (print)

Subjects: LCSH: Racism in sportsUnited StatesHistory20th century. | Discrimination in sportsUnited StatesHistory20th century. | African American athletesHistory20th century. | African American athletes Biography. | Civil rights movementsUnited StatesHistory20th century.

Classification: LCC GV706.32 (ebook) | LCC GV706.32 .M66 2017 (print) | DDC 306.4/83dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017019469

ISBN: 978-1-4408-3952-8 (print)

978-1-4408-3953-5 (ebook)

21 20 19 18 171 2 3 4 5

This book is also available as an eBook.

Praeger

An Imprint of ABC-CLIO, LLC

ABC-CLIO, LLC

130 Cremona Drive, P.O. Box 1911

Santa Barbara, California 93116-1911

www.abc-clio.com

This book is printed on acid-free paper

Manufactured in the United States of America

Contents

This book was a pleasure to research and write. I would like to thank Steven Riess for recommending me to Praeger for this project. Thanks for believing in my work. A special thanks goes to the Twitter world, who put up with my tweets about sports and civil rights and gave me the confidence to write this book. I also appreciate all the scholars, including Adrian Burgos, Derrick White, Matthew Klugman, and Michael Ezra, who encouraged me throughout this process. Eric Paul has been a rock since grad school. My father-in-law, Willie Jones, has treated me like a son since day one. To my friends since grade school, Mark, Todd, Larry, and Damion, thanks for always being there. A special thanks to my brother, Lance, who taught me to love sports, and my sisters, Zenobia and Zoey, who brag about me to their friends. My mom, Mary, gave us everything when we had nothing. Most important, my wife, Ciciley, made this all possible with her endless support and love. And finally to Amaya, Grant, and Islayou are the greatest gifts and kids in the world. Thanks for your patience while Daddy got his work done. I love you.

James Mudcat Grant would not sing the right words. He knew they were a lie. Home of the Brave. Land of the Free. For who? Not black Americans. Not in 1960. Grant remembered vividly growing up in poverty in Lacooche, Florida, in a shack that had no hot water, electric lights, or an indoor toilet, while his widowed mother supported her family on her menial wages working as a domestic in white peoples home and then trying to supplement her meager wages at the local citrus plant. He remembered the white kids who would bully the black kids and call them racist names, the white cop who pointed a gun at him while his partner kicked him in the rear, and the unequal school system where black kids received old school supplies deemed unfit for white kids, where he studied in a school that was really a house with blankets dividing the classrooms. There were the segregated spring training games in Florida, his Cleveland Indians teammates who yelled racist remarks at black fans, and his pitching coach, Ted Wilks, who in 1947 as a member of the St. Louis Cardinals tried to organize a boycott to avoid playing Jackie Robinson and the Brooklyn Dodgers, and as a pitcher regularly threw at the heads of black batters.

And that was just Grants individual reality. He knew his people were starving, were segregated, and had to live under the daily indignities of Jim Crow. And he knew they were fighting for their equality. He would not sing the words of the national anthem that day. He was fed up. When he got to the end of the song, he changed the lyrics to reflect his reality, what black Americans had to live with. He added, This Land Aint so Free. I Cant Even go to Mississippi. That remix set his freedom-loving racist pitching coach off. The Texan, Wilks, told Grant, If you dont like it here, why dont you get [out of here] Nigger. To which Grant replied, Texas was no better than Russia. With that, Wilks threatened his pitcher and told the black man that hed better not catch his black ass in Texas. Grant, a fiercely proud black man, refused to deal with these insults, so he packed his bags and left the stadium. For leaving, the Indians suspended him for two weeks, the rest of the season. The racist pitching coach, Wilks? Nothing happened to him. Wilks represented another hypocritical white man, just like the white players who sang the national anthem, or as one black player put it, when they sing about the land of the free all of em gotta have their tongues in their cheeks when they do it.

While the incident barely made a ripple in the white daily press, black writers were all over the ordeal. They were waiting for another black athlete like a Jackie Robinson, Elgin Baylor, or a Bill Russell, who publicly fought back against American racism, who battled against the narrative that black athletes should just shut up and play. It was time for the black athlete to give back to the movement. Black writers praised Grant for his stance and suggested he was a member of the new school of Americans, who refuses to bend his principles for a price, and many denounced his teammate, pitcher Don Newcombea favorite among the black community since he broke in with the Dodgers in 1948who witnessed the incident but did not challenge his racist coach. Newcombe represented the old black athlete who whites expected to keep quiet and remain in their place. As L. I. Brockenbury of the Los Angeles Sentinel put it, Don, like Roy Campanella, and unlike Jackie Robinson, feels that a Negro should feel so honored to be with a white team that he should take just about anything. In one defiant moment, James Mudcat Grant, the star pitcher raised in Jim Crow poverty, articulated the plight black Americans faced in sports and society.

Although Grants defiance was just one incident, and Grant apologized profusely for leaving the stadium, Grants protest and the support he received from the black press encapsulated the relationship between the black athlete and the black community during the civil rights movement. The moment and support indicate that during the civil rights movement, African American activists and athletes fought together to break down the barriers of Jim Crow in sports and society. Though sports might seem trivial during a time when black protesters were being arrested, beaten, and even killed for fighting for equal rights, as black sportswriter Claude Harrison Jr. of the Philadelphia Tribune acknowledged in 1964 when discussing the lack of black quarterbacks in professional football, While this is no secret and no burning issue with the Negro fans, now, that there are more important issues such as the Freedom fight, riots and the drive to defeat Barry Goldwater, it does bother me. Hall believed that the success of black athletes helped defeat negative stereotypes of black people and thus proved blacks were individuals worthy of equal rights.