Specializing in the study of race and Southern history as well as social and cultural history in post-World War II America, Schutz is currently completing a study of the 1972 Charlotte Three case (which targeted Black Power activists in North Carolina). He is professor of history at Tennessee Wesleyan College.

Afterword

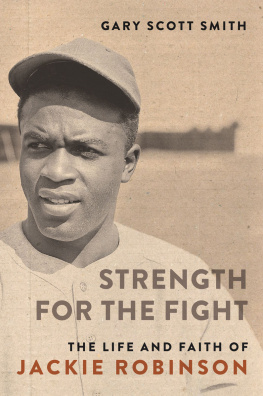

Jackie Robinsons legacy runs far beyond his funeral cortege. Perhaps most immediately, he left an indelible mark on athletics and the African Americans who would seek to enter them for generations to come. Just before his death, Sport magazine feted Robinson as the most significant athlete of the past quarter century. Delivering an appreciation, black basketball legend Bill Russell acknowledged that he rarely attended such banquets but made a notable exception for Robinson. I never saw him play ball, Russell conceded. But I would go halfway around the world to honor him because he was and is a man. Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, whom two Hall of Fame peers named the greatest basketball player who ever lived, wrote this poignant diary entry on his birthday during his final season in 1989:

My thoughts are on Jackie Robinson today, my birthday. I was born in Harlem the day after Jackies first major league game across the river in Brooklyns Ebbets Field. It was forty-two years ago that I was born and that Jackie Robinson, in 1947, at age twenty-eight, crossed baseballs color line. I have always considered it a gift that I slipped into the world just at that moment. All the courage and competitiveness of Jackie Robinson affects me to this day. If I patterned my life after anyone, it was him.

Hank Aaron (who followed Robinson into the Majors from the Negro Leagues by twenty years) would have to brave racist abuse on his way to conquering the revered Babe Ruths long-standing home run record in 1974. He maintained that he never dreamed of the big leagues until Jackie broke in with the Dodgers in 1947. Robinson, he contended, was the Dr. King of baseball.

But the greater meaning of Robinsons life, of course, is how he used a bat and glove to battle the racial fears and barriers of his day. Rachel Robinson recalls that when her husband first took a Major League field, the meaning of the moment for me seemed to transcend the winning of a ballgame. The possibility of social change seemed more concrete, and the need for it seemed more imperative. I believe that the single most important impact of Jacks presence was that it enabled white baseball fans to root for a black man, thus encouraging more whites to realize that all our destinies were inextricably linked. Sportswriter Leonard Koppett claims that Robinsons arrival compelled millions of decent white people to confront the fact of race prejudicea fact they had been able to ignore for generations before. The consequences of the waves his appearance made [in baseball games across the country] spread far beyond baseball to the very substance of a culture.

Author Roger Kahn recalls how Robinsons teammates

marched unevenly against the sin of bigotry. That spirit leaped from the field into the surrounding two-tiered grandstand. A man felt it; it became part of him, quite painlessly. Below, Robinson lines a double into the left-field corner. He steals third. That colored guys got balls, I tell you that. By applauding Robinson, a man did not feel that he was taking a stand on school integration, or on open housing. But for an instant he had accepted Robinson simply as a hometown ball player. To disregard color, even for an instant, is to step away from the old prejudices, the old hatred. That is not a path on which many double back. Everywhere, in New England drawing rooms and on porches in the South, in California, which had no major league baseball teams and in New York City, which had three, men and women talked about the Jackie Robinson Dodgers, and as they talked they confronted themselves and American racism. That confrontation was, I believe, as important as Brown vs. Board of Education of Topeka, in creating the racially troubled hopeful present.

That story played itself out in very personal ways, such as Dodgers radio announcer Red Barber. Born and raised in the South, Rickeys advance warning to Barber that a black player was coming to the Dodgers left him shaken to my heels. He returned home telling his wife that he must quit his job, as he could not stomach the thought of announcing an integrated team. It tortured me, Barber recounted. But after some agonizing reflection, he arrived at the conclusion that [a]ll I had to do was treat him as a man, a fellow man, treat him as a ballplayer, broadcast the ball. That alonethe very act of seeking simple neutrality on Robinsons racewas life altering. And without Robinsons arrival forcing the issue, Barber might have gone many years longer not confronting the racial skeletons rattling in his closet. But arrive Robinson did, carrying the weight of a race with him, and compelling Barber to do a deep self-examination. I attempted to find out who I was. I know that if I have achieved any understanding and tolerance in my life it all stems from this. Those reformed convictions were passed on to his daughter, who was to volunteer as a teacher of young black children in Harlem.

The very fact of Robinsons presence itself became an early harbinger of the racial change that lay ahead. As Branch Rickey put it, Integration in baseball started public integration on trains, in Pullmans, in dining cars, in restaurants in the South, long before the issue of public accommodations became daily news. Even Roy Campanellanot known as a civil rights crusadercame to claim, All I know is that the ball clubs going down [to the South] and playing together, and traveling together, and then eating together and all, we were the first every time; we were like the teachers of it. Teammate Don Newcombe went further: We were paying our dues long before the civil rights marches. Martin Luther King told me, in my home one night, Youll never know what you and Jackie and Roy did to make it possible to do my job. King once confided to close aide Wyatt Tee Walker that without Robinson, I would never have been able to do what I did.

One notable difference between Robinson and his famous athletic forerunners, Joe Louis and Jesse Owens, was that Robinsons arrival came in the midst of a team (rather than the individually oriented achievements of boxing and track). While entering a team sport forced Robinson into the uncomfortable terrain of the repeated encounters with reluctant whites and their locker room, it also came to symbolize more powerfully the broader societal integration of the 1950s and 1960s. Robinsons daily interactions on the diamond stood metaphorically for American society in a quite visible and public way. The collective nature of baseball thus allowed some whites to imagine white players as stand-ins for the more receptive whites in American society, who heroically made possible the project of integration.

In 2005, the Class A Brooklyn Cyclones baseball club unveiled a statue of two men, side by side, one black and one white. They stand simply enough, in Brooklyn Dodgers uniforms, the white player draping his arm around the black. It is meant to depict a now famous, decidedly human, moment in the story of Jackie Robinson. Amid white fans racist taunts during Jackies first year in the Major Leagues, Dodgers shortstop Pee Wee Reese sauntered over to his African American teammate and put his arm around him, silencing the crowd. The gesture, remembered so fondly to this day, spoke volumes. It said Robinson and his fellow blacks are here to stay. It said I, a white man, stand with this black man. It said, of course, we are all on the same team after all. In his later years, Reese could only say of the moment, Something in my gut reacted at the moment. Something about what? The unfairness of it? The injustice of it? I dont know.