CONTENTS

Guide

List of Illustrations

- Chapter 1

- Chapter 2

- Chapter 3

- Chapter 4

- Chapter 5

- Conclusion

Pages

Black Lives series

Elvira Basevich, W. E. B. Du Bois

Utz McKnight, Frances E. W. Harper

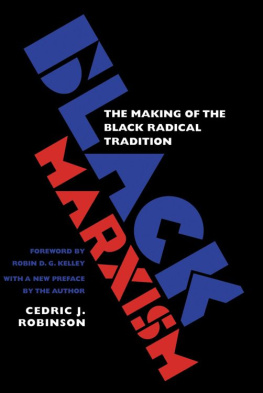

Joshua Myers, Cedric Robinson

Cedric Robinson

The Time of the Black Radical Tradition

Joshua Myers

polity

Copyright Joshua Myers 2021

The right of Joshua Myers to be identified as Author of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

First published in 2021 by Polity Press

Polity Press

65 Bridge Street

Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press

101 Station Landing

Suite 300

Medford, MA 02155, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-3793-8

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Names: Myers, Joshua (Joshua C.), author.

Title: Cedric Robinson : the time of the Black radical tradition / Joshua Myers.

Description: Cambridge, UK ; Medford, MA : Polity Press, 2021. | Series: Black lives | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Summary: The first account of the radical thought and life of the great Marxist critic of racial capitalism-- Provided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021002734 (print) | LCCN 2021002735 (ebook) | ISBN 9781509537914 (hardback) | ISBN 9781509537921 (paperback) | ISBN 9781509537938 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Robinson, Cedric J. | Communists--Biography. | African American communists--Biography.

Classification: LCC HX84.R576 M94 2021 (print) | LCC HX84.R576 (ebook) | DDC 335.4092 [B]--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021002734

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021002735

The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website: politybooks.com

Acknowledgments

The journey toward this book began with Robin D. G. Kelley, who has been instrumental both behind the scenes and in direct ways, in realizing its completion. Robins initial work on many of the biographical details of Cedric J. Robinsons life was both inspiration and guide. His faith was also a steadying force. And his clearing of the way to Elizabeth Peters Robinson was indispensable. Without Elizabeth, this work would have never happened. She opened her home and heart to me in ways that I am still fully understanding. She provided not only access to an archive, she provided access to a way of feeling this life. I offer my unstinting gratitude to her and to the many people she placed before me as necessary witnesses to Cedrics life: Gerard Pigeon, Joanne Madison, Marisela Marquez, Avery Gordon, Gerardo Gary Colmenar, and Matthew Harris, among others. Gerard, Joanne, Marisela, and Avery stopped what they were doing and agreed to talk about their experiences with him. Gerard was Cedrics best friend and one of the most significant commenters on Cedrics character. My conversations with Avery proved to be very necessary in shaping aspects of the book. Gary was a remarkable help in securing necessary archives from the University of California, Santa Barbara campus during the coronavirus pandemic. I am grateful to him and Matt Stahl of the library for making a very large cache of materials available to me. I am extremely indebted to Matthews work in organizing and processing the Robinson papers, which are still held in private. Without that work, my task of engaging that bounty would have been next to impossible.

Cedric J. Robinsons students were a source of grace. I do not take their generosity for granted. I thank H. L. T. Quan for not only agreeing to an interview, but for graciously reading the manuscript and taking time to participate alongside Elizabeth, Robin, and me in a 2020 panel on Cedric that greatly impacted the book. My conversations with Tiffany Willoughby-Herard were deeply insightful. Not only did I find out that she was my South Carolina homegirl, but the care in which she outlined her memories of Cedric and what they mean for now, for the present, and the future of Black Studies will stay with me. Darryl C. Thomas gave me a clear picture of the earlier years and the important time the Robinsons spent in Michigan. I was also able to speak with Bruce Cosby, who took classes with Cedric at Binghamton. And Fred Moten who, though never a formal student of Cedrics, considered himself in this number as a younger colleague. All of these students and/or mentees are now scholars in their own right, a testament to Cedrics impact. There are many more whom I must thank, though we did not get a chance to speak about this project formally: Damien Sojoyner, Jordan Camp, Christina Heatherton, Greg Burris, Jonathan D. Gomez, Rovan Locke, Erica Edwards, and Ruth Wilson Gilmore.

Tracking down Cedrics comrades from his early years proved to be daunting. But I was thankful to find Ken Cloke, one of the organizers of the Berkeley Free Speech movement, who put me into contact with Mike Miller, an organizer of SLATE and eventually the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. Miller remembered Cedric for, among other things, donating blood to him when he returned to the Bay Area after being injured in a car accident while organizing in Mississippi. He then connected me to Margot Dashiell, who was able to share with me her impressions of Cedric as a young activist who was connected to the UC chapter of the NAACP and to the emerging Afro-American Association. It was Dashiell who clarified so much about Berkeley history, Bay Area Black nationalism and radicalism, and other tidbits during those days, and I hope she is able to tell her story soon. She also graciously showed me letters that Cedric wrote her from Mexico, southern Africa, and Fort Sill, Oklahoma that she held onto for over fifty years. Others from that period in Cedrics life that I interviewed included Nell Irvin Painter and J. Herman Blake, two scholars whom I consider to be giants in their own right. Their recollections helped me properly paint a picture of his life during those formative moments. The oldest friend that I was able to speak to was Douglas Wachter, whose testimony before the House Un-American Activities Committee led to the events of May 1960. I am grateful to Douglas for his memories of Cedrics junior high years.

Though there were many collections held in private, I did have an opportunity to track Cedric and the larger movement to several formal holdings at the Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, The Oakland Public Library, The African American Library Museum at Oakland, the Bentley Historical Library, Binghamton Universitys Special Collections, and the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. I thank the many librarians and archivists who smoothed the way. I want to offer a brief note of thanks to Pendarvis Hardshaw, a true brother of the Town, who offered his help in connecting to Oakland sources. As far as libraries are concerned, I want to thank my cousin Dr Kayla Lee, who used her library access to help me secure some of Cedrics earliest articles when I first began to work on this text. Thankfully, some of those articles are now more widely available. Richard E. Lee, Resat Kasaba, and Beverly Silver directed me to several places to help me unpack Cedrics relationship to Terence Hopkins. Yousouf Al-Bulushi graciously sent over audio files digitized from Cedrics collection that proved necessary.