Futures of Black Radicalism

Edited by Gaye Theresa Johnson

and Alex Lubin

First published by Verso 2017

Contributions The Contributors 2017

Collection Verso 2017

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-78478-758-5

ISBN-13: 978-1-78478-757-8 (US EBK)

ISBN-13: 978-1-78478-756-1 (UK EBK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Johnson, Gaye Theresa, editor of compilation. | Lubin, Alex, editor of compilation.

Title: Futures of Black radicalism / edited by Gaye Theresa Johnson and Alex Lubin.

Description: London ; Brooklyn, NY : Verso, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references. |

Identifiers: LCCN 2017009449 (print) | LCCN 2017013686 (ebook) | ISBN 9781784787578 () | ISBN 9781784787561 () | ISBN 9781784787585 (paperback) | ISBN 9781784787578 (ebook : US) | ISBN 9781784787561 (ebook : UK)

Subjects: LCSH: African AmericansPolitics and government. | BlacksPolitics and government. | RadicalismUnited States. | Radicalism. | RadicalsUnited StatesBiography. | RadicalsBiography. | United StatesRace relationsPolitical aspects. | Race relationsPolitical aspects. | InternationalismPolitical aspects. | Anti-globalization movement. | BISAC: SOCIAL SCIENCE / Ethnic Studies / African American Studies. | SOCIAL SCIENCE / Black Studies (Global). | POLITICAL SCIENCE / History & Theory.

Classification: LCC E185.615 (ebook) | LCC E185.615 .F88 2017 (print) | DDC 323.1196/073dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017009449

Typeset in Minion Pro by Hewer Text UK Ltd, Edinburgh

Printed in the UK by CPI Mackays

Contents

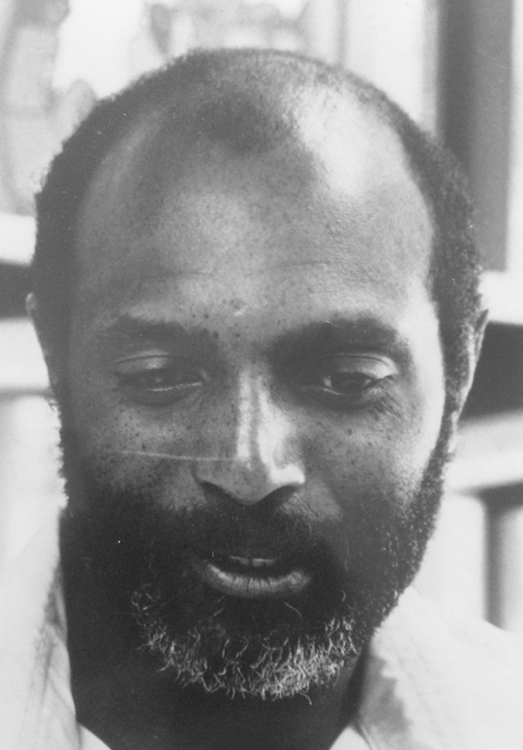

When Cedric committed to preparing this preface, he did so on the condition that we do it together, perhaps already aware that his health was failing, but at a rate neither of us anticipated. Alas, his death has left the task in my hands and though we had talked about some possibilities, we wrote not a word together. I would never presume to speak for him despite our fifty years together. Our styles have always been too different, mine more journalistic, sometimes more polemical. His analytic, elegant, meticulously documented. And always going to places I could never anticipate. So I have sat for months trying to figure out how to procede and have finally been delivered thanks to the transcription of a series lectures he gave at UC Irvine in 2012. Thank you, Tiffany Willoughby Herard for organizing the seminar, Kyung Kim for videoing it, and Mohsin Mirza, Yoel Haile, and Marisela Marquez for providing me with the transcription. Much of what you read is literally in Cedrics voice with only minor corrections from me. His contributions, in italics, were unwritten, so they lack his usual copious footnotes and careful construction. And it is impossible to convey the humor, emphasis, et cetera, of the seminar. But I hope that it gives you a sense of Cedric as teacher.

Elizabeth P. Robinson

Joshua Fit De Battle

This story in some places might exaggerate possible actual events, but if the truth is here, it can be found. The theme is segregation.

Joshua Cole, a negro of sixty or more years, was sitting on the old broken steps of his shack on his side of town, thinking of the sun and how hot it was, when his musing was interrupted by someone calling his name, Joshua, Josh Cole, the excited voice cried, Josh yo Freddy is dead!

Suddenly realizing what was being said, Joshua rose quickly then fell back onto the wall of the building, more weight on his shoulders than even his age could account for.

The facts were made known to him, one by one. One of his neighbors, Zeke, had found the body of ten-year-old Freddy near the old tracks in the bushes. His neck was broken, not from a rope but a mighty blow

Going inside his shack, Joshua confronted Zeke who rapidly told Joshua in his eighty-year-plus-voice what he had seen. Zeke had done more than find the body, he had been sleeping in the nearby brush when Tom Caspine had chased Freddy after the boy had called Tom white trash. Caspine had turned red with rage and had struck the boy with a vicious sweep of his fist. Caspine had left the boy lying in a peculiar position, not noticing the sightless eyes of the peculiarly positioned head

His last words before his blood flowed like wine, were Lord, aint you nevah goin to give the world to the meek?

Cedric Robinson

Jan. 8, 1957, English V

The last line in the essay quoted above was penned in the pall of the lynching of Emmett Till, as well as the promise of the mid-twentieth-century Civil Rights movement. The story was about a brutal murder of a Black child and the denial of justice in the aftermath. In looking for the antecedents of Black radicalism, we should consider our individual moments of awakening. Was this one? Or maybe listening to an old mans stories of courage and valor as his grandson helped him mop floors in government buildings. We might consider the little girl in Detroit who found something like the life of Sojourner Truth to read every day over breakfast. Maybe a young Arab womans discovery that the movie Exodus told a particular and peculiar history of Palestine and that race and racism were entirely mutable. Or maybe being scolded for addressing a Black man as Sir. Surely the affronts that are experienced because weve had the audacity to be somewhere we dont belong, the racial taunts and aggressions experienced repeatedly must be factored in to the formation of our racial identities. But the critical moment comes when we realize the political, historical, and social connectedness of those experiences and move from the personal, however important it might be, to the necessity of engagement, to the Black radical tradition. Also, to remember that this is not only about pain, but also about shared knowledge, joy, and humor that are integral to those experiences.

In compiling this collection of essays, the editors and authors invite or insist that we project a tradition, Black Radicalism, into the future. It is certainly our intention to celebrate that and suggest some ways in which we can find inspiration in our histories for our present moment. In the latter, we are confronted daily with police lethality and other abuse, mass incarceration, and a politics of greed. It is difficult to keep feelings of depression and defeat at bay, but our histories, perceived in all their dynamism, their resistance and resilience, can give us heart and direction. Our pasts are not dead; why else are there repeated attempts to bury them, to erase or forget them? Why does generation after generation have to rediscover W. E. B. Du Bois, Pauline Hopkins, Oliver Cox, and so many others? How is it that the indigenous people at Standing Rock, North Dakota, are telling us about massacres weve never heard of? Why dont we know about Black and white workers who made common cause for mutual benefit? Beyond US borders, why is it not common parlance that peoples movements from Vietnam, Algeria, Iran, Lebanon, South Africa, Zimbabwe, Chile, Guatemala, to name but a few, were undermined or simply destroyed by Western capitalist greed and militarism? Perhaps it is simply too painful to remember these assaults; but burying them also buries the rich histories of resistance. While slavery and emancipation are part of our official histories, maroons and marronage, Palmares, quilombos, and the Great Dismal Swamp are unknown or little known when they should be the bedrock of contemporary struggles.