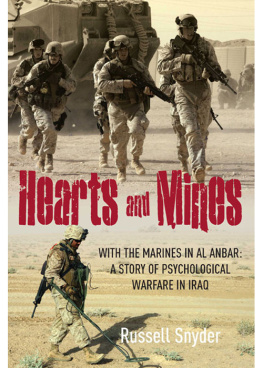

Published in the United States of America and Great Britain in 2011 by

CASEMATE PUBLISHERS

908 Darby Road, Havertown, PA 19083

and

17 Cheap Street, Newbury RG14 5DD

Copyright 2012 Russell Snyder

ISBN 978-1-61200-105-0

Digital Edition: ISBN 978-1-61200-117-3

Cataloging-in-publication data is available from the Library of Congress and the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Printed and bound in the United States of America.

For a complete list of Casemate titles please contact:

CASEMATE PUBLISHERS (US)

Telephone (610) 853-9131, Fax (610) 853-9146

E-mail:

CASEMATE PUBLISHERS (UK)

Telephone (01635) 231091, Fax (01635) 41619

E-mail:

CONTENTS

For Nichole, in fulfillment of a promise.

For the men of the United States Marine Corps.

For the people of Al Qa'im.

For peace.

In fallow fields the wheat still grows

Though no one comes to tend the rows

But tanks and soldiers as they sweep

Across the barren plain and seek

To sow a seed of hope

For evil still pervades this land

Grasping with a withered hand

The breath of men from far away

Who wait upon their Judgment Day

In hopes that each by God is blessed

As they confront their greatest test

Of courage and morality

Where everyone has lost a friend

Each man looks forward to the end

Searching for a reason why

So many people here must die

Before shafts of wheat may rise once more

And beauty to the land restore

AL QA'IM, IRAQ

2005

Authors Note

The names of individuals throughout this book have been changed to protect their identities. Dialogue, where it appears, has been constructed from memory. Though quotations embody the spirit of what was said, they should not be considered exact transcriptions of conversations. I have attempted to recreate as faithfully as possible the actual events upon which this book is based from my own notes and memories, as well as the memories and resources of other participants, but it is possible others may present them differently. I am also deeply indebted to Richard Kane, my editor. His excellent work and professional wisdom have helped me to realize a better book. Any errors that remain are my own.

Mankind must put an end to war, or war will put an end to mankind.

JOHN F. KENNEDY

PREFACE

F our years have passed since I first was introduced to war. Four years have dulled my memories, and the emotions connected with them have faded. Yet the urge to purge my mind of those unforgettable days that have since and forever influenced my attitude on life, to come to terms with the weight upon my conscience, still gnaws at the edge of my waking mind. Several times I have started and failed to complete this written record of my experience, having always dreaded the confrontation with painful remembrances and doubting whether my small part in the greater story constituted a portion much worth telling. In the twilight of my third deployment to Iraq, the personally held importance of doing so has not seemed to lessen. I know mine is not an uncommon story. I know that if I have suffered, I have not done so to any greater degree than many millions who have shared in the conflict since the war began in 2003, and certainly not more so than have the veterans of previous wars. There are many dead men whose stories deserve to be told more than mine. The triviality, the selfishness, of sharing my small role feels almost shameful. But I can no longer deny my compulsion to complete this task, to glean from the pages of my wartime journal a work worthy of preserving the memory of the lives destroyed around me. I hope as well that the peace I seek may come if I can at last give voice to my thoughts and account to myself, to whatever constitutes my feeling of the presence of God, and to the ghosts of war.

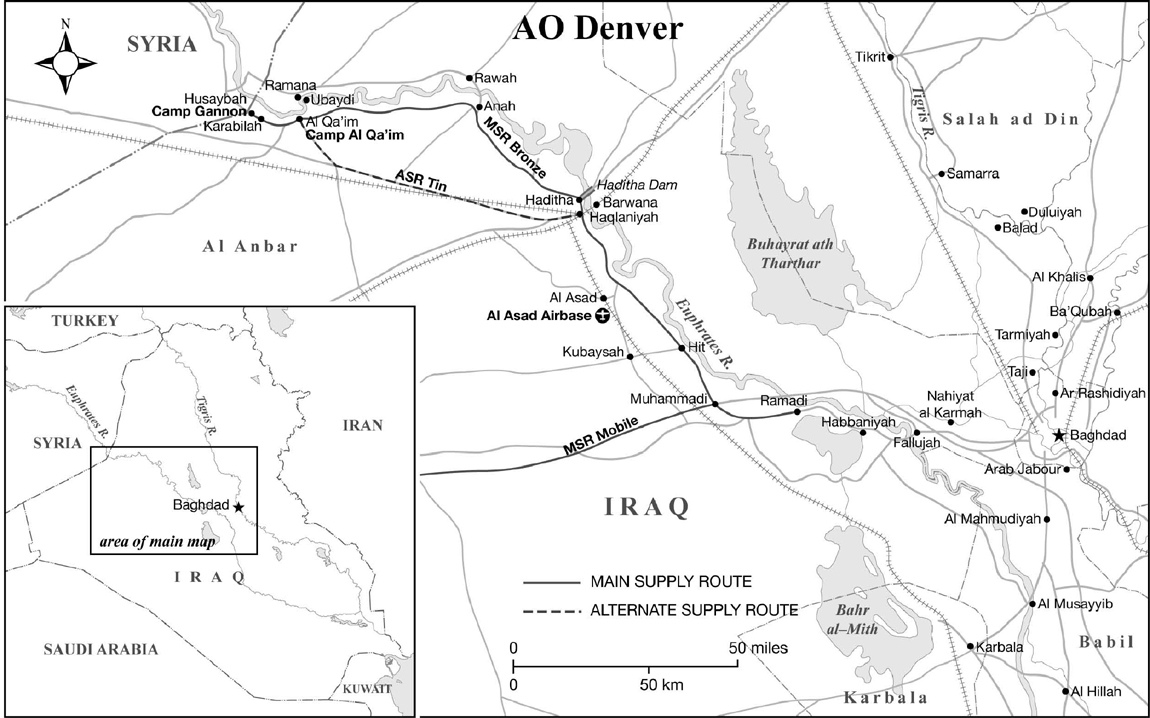

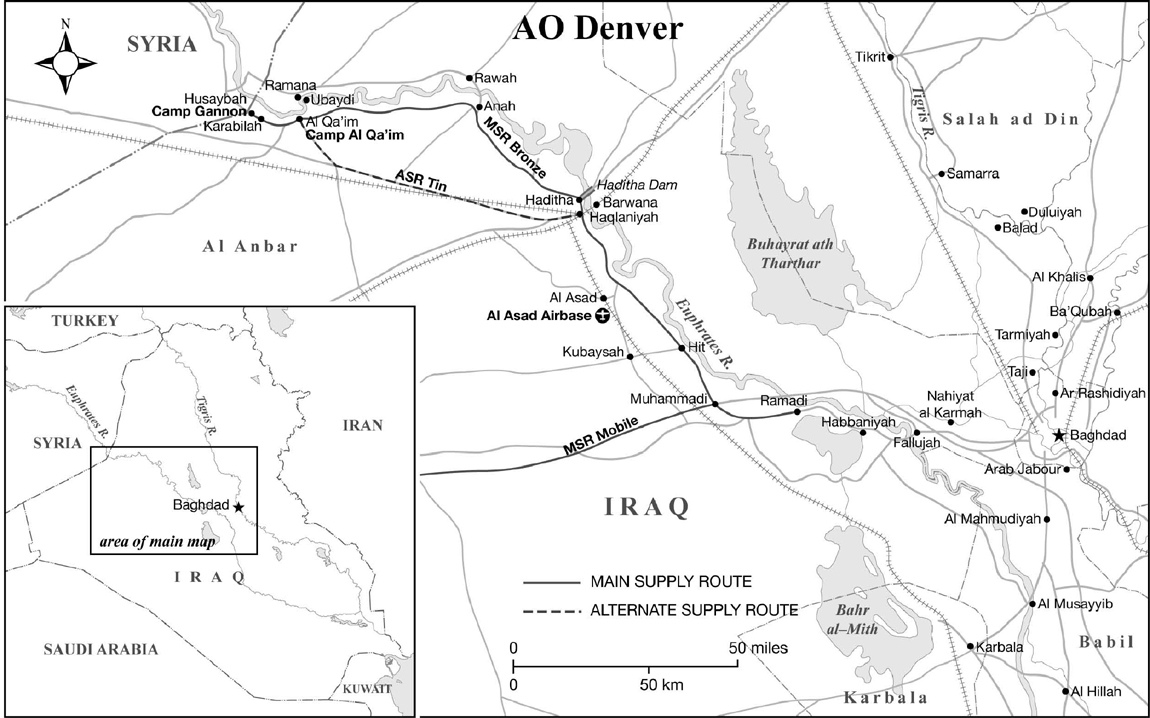

This is the story of my preliminary wartime experience. These are my memories of life as a member of one of the U.S. Armys three-man tactical psychological operations teams (TPTs). While attached in support of the United States Marine Corps 3rd Battalion, 2nd Marines, and 3rd Battalion, 25th Marines, operating along the Euphrates river valley in western Iraqs Anbar desert during the spring and summer of 2005, I witnessed what was at that time some of the most vicious counterinsurgency fighting of Operation Iraqi Freedom since Fallujah.

I do not claim to be a historian, or even to have been privy to the big picture of the war reserved for the generals and their staff. Nothing I did was heroic or changed the course of history or any battle. Mine was the perspective of a low-ranking sergeant, isolated from the medias reports and influenced by the stresses of fatigue, fear, and moral uncertainty. Doubtless there are details in the collective record of the wars participants I am unaware of or have forgotten. Others may remember the same events differently. Some things, as well, should frankly not be said. But as for the memories of one soldier who was there, what follows is what really happened.

INTRODUCTION

I have stopped dreaming so often of the war. I cant remember when exactly, but one night, to my relief, the nightmares didnt come again. It was the first night in months, ever since my return from Iraq to the United States, that I hadnt revisited the dusty streets of Anbar in my sleep. The faces of dead friends and strangers remain clear in my minds eye as I write, but I am no longer haunted by them. They live on with the feeling of a smooth, warm stone in the pit of my stomach: not uncomfortable, but never quite forgotten. Neither are the events of my first eight months in Iraq, for I decided early in the deployment I would make a journal entry each day to preserve the experience for myself and perhaps to communicate my daily thoughts to my family in the event of my death.

It is not that I had any particular fear of dying, because I did not understand death. Rather, a strange fascination with mortality had begun to haunt my thoughts over the past months. Previously, Id not known more than a handful of people whod died, but as that reality changed, so too did my youthful perception of myself as invulnerable. My friend Jon had been a member of the company my unit replaced, and just a few months before our arrival lost his life when a suicide car bomber attacked his team in the same area my team would later be assigned to patrol. After arriving at the dead mens former base, I walked into their office in the abandoned train station at Al Qaim and discovered a small but poignant collection of reminders that they had never returned.

Most of the three mens personal effects had of course been packed up and shipped to their next of kin, but left behind were a few items like the heavy black power converter upon which someone had written the numbers Nine-Five-One with a white paint marker.

Nine-Five-One signified belonging to the first team, of the fifth detachment, of the armys Ninth Psychological Operations Battalion. To the Marines or soldiers who packed up Jons things and forgot the converter, they meant nothing more, but to me, the numbers meant my friend had touched the object, used it to charge his laptop or his music player, and never been back to take it home with him. They reminded me of his face, a memory that would never age. Years after his death I still remember Jon as I last saw him, alive and smiling in the glow of a backyard campfire, surrounded by the friends who loved him. I think of the young family he left behind, and the arguments we never resolved. The legacy of his life, a speck among the millions death has claimed through war, one I took for granted, deserved to be counted as more than just a number. It was a life worth remembering, and the loss of it forced me to confront the keen possibility that I, too, might die.

Next page