SARAH A. CORBET, SCD

PROF. RICHARD WEST, SCD, FRS, FGS

DAVID STREETER, MBE, FIBIOL

JIM FLEGG, OBE, FIHORT PROF. JONATHAN SILVERTOWN

The aim of this series is to interest the general

reader in the wildlife of Britain by recapturing

the enquiring spirit of the old naturalists.

The editors believe that the natural pride of

the British public in the native flora and fauna,

to which must be added concern for their

conservation, is best fostered by maintaining

a high standard of accuracy combined with

clarity of exposition in presenting the results

of modern scientific research.

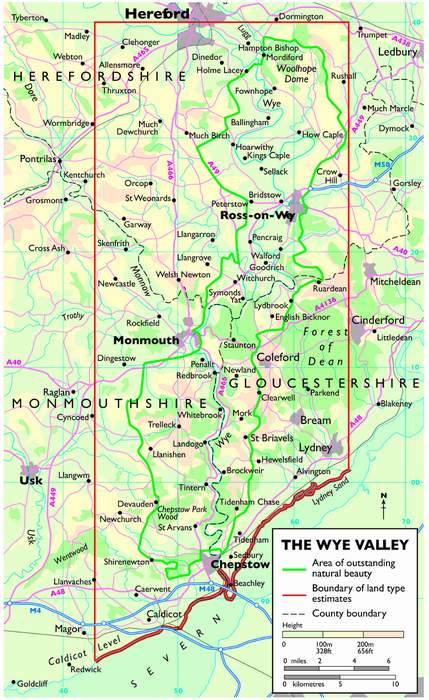

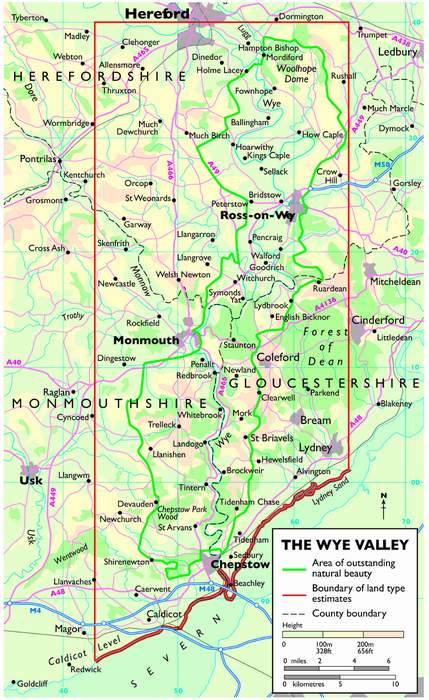

FRONTISPIECE. The Wye Valley. The boundary of the AONB defines the core of the Lower Wye. This has been boxed into a larger area within which landscape districts have been recognised and the extent of land types has been estimated (see Chapter 3).

I N 2006 WE INTRODUCED the first New Naturalist regional volume on an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty with Jonathan Mullards Gower. Last year we followed this with Rosemary Parslows The Isles of Scilly whilst Derek Radcliffes Galloway and the Borders encompasses no fewer than five National Scenic Areas, the Scottish equivalent to AONBs. We continue the AONB theme with the Wye Valley, one of the most famed landscapes in lowland Britain. Popularised by 18th and 19th century authors like William Gilpin and Thomas Roscoe, the dramatic limestone gorges, the spectacular views from Yat Rock and the beautiful medieval monastic remains of Tintern Abbey became major attractions for Victorian tourists.

This book is primarily about the Lower Wye Valley from Hereford to Chepstow, where the river joins the Severn, together with the neighbouring parts of Monmouthshire, Gloucestershire and Herefordshire. Not without reason does George Peterken claim that the Wye is arguably the finest and least spoiled of all the major rivers of Britain. It is also important geographically, as for much of its length it forms the boundary between England and Wales, and from a natural history point of view the woods that clothe the valley sides are among the finest in the country.

George Peterken is one of our leading authorities on woodland ecology and forest management and the author of a number of major works, including Woodland Conservation and Management (1981) and Natural Woodland (1996). His familiarity with the area stretches back almost forty years to when he first joined the then Nature Conservancy as a woodland ecologist. The Wye Valley became an interest and in particular he became closely involved, with the late Eustace Jones, in the research into the ecology of the Lady Park Wood National Nature Reserve that had been initiated in the 1940s by the Forestry Commission and Oxford University. After retirement George moved to the Wye Valley, becoming closely involved with local conservation initiatives, including the establishment of a Parish Grasslands Project. He worked as a forestry consultant for both the Forestry Commission and Forest Enterprise and is now a member of the National Trusts Conservation Panel. He is President of the Gwent Wildlife Trust as well as an associate professor of Nottingham University. In 1994 he was awarded the OBE for services to forestry.

Despite its fame, George describes the Wye as the unknown river. We are confident that with Wye Valley he has now rendered his own description redundant and that his masterly synthesis of the areas history and natural history will enthuse all those that read it with his own affection and enthusiasm for this special part of Britain.

I FIRST SAW THE Lower Wye Valley in 1960 when, like Chesterton going to Brighton by way of Timbuktu, I was driving from London to a field course at Malham Tarn. We merely crossed the valley at Monmouth on our way to pick up a friend in Oakwood, but I saw enough to know I had to return. Later, in 1965, we drove from Aberystwyth to Cornwall and crossed the Severn on the Aust ferry, but it was not until 1969 that I got to know the area well. Newly appointed as a woodland ecologist by the Nature Conservancy, one of my earliest jobs was to survey the woods of the proposed Wye Valley Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty official work, certainly, but a great pleasure. Internal politics brought me a directive not to do this work, but, shielded by my line manager, I came anyway, and thereafter I accepted every opportunity to work in the district. In 1980 I was drawn into a debate about the future of Lady Park Wood, the reserve above the Biblins bridge where, in 1944, Oxford University had started a long-term research project, and I have been involved there ever since. Then, in 1993, having become an independent ecologist, we cast around for somewhere attractive to live, and settled on St Briavels Common, overlooking the valley just above Tintern.

At the time of our arrival as residents, I knew a good deal about the woods, but little about other aspects of the Lower Wyes natural history. However, our house was part of a smallholding comprising nine acres of flower-rich meadow, as well as four acres of the locally characteristic beech-oak-lime-hazel woodland, so perforce we learned about grasslands and their management. In fact, I went further. First, I helped to draft the AONBs Nature Conservation Strategy, launched in 1999. Then, realising how vulnerable the landscape of semi-natural grassland in tiny fields into which we had moved had become, I joined with neighbours to start a parish grassland project that aims to help residents look after their local environment.

The feature that stamps its character on the region is the Wye gorge from Goodrich south to the Severn. With its great limestone cliffs, extensive ancient woods, numerous remnants of semi-natural grassland, the estuary below Chepstow and a river that at least appears to be natural, it has long attracted tourists and natural historians. Its context, too, is attractive. Upstream, the Wye passes through southern Herefordshire in great meanders that separate the Woolhope Dome and the northern extremities of the Forest of Dean from the rolling sandstone farmland along the Welsh border. To the east and west, limestone and sandstone uplands descend to the Levels, a fringe of former marshland beside the Severn that has great ecological and archaeological value. This book is therefore not just about the immediate valley, which actually occupies a rather small area, but also the district through which it passes, a region that for convenience I will label the Lower Wye. The title, however, is Wye Valley for, as explained by A. G. Bradley (1910), If peradventure the traveller has come to Ross from Hereford by way of the high country upon the east bank of the Wye he will understand, before he begins the long downward slope to the town, why its people call it the gate of Wye. For the Wye, as the world in general knows, begins here.

The book tells two, contrasting stories. One describes and celebrates the ecology, natural history, landscape and history of a district that is officially regarded as unspoiled enough to become an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. The other recognises that 70% of the region is intensively farmed and that the protection afforded to the outstanding natural beauty has not protected natural habitats and wild species from substantial losses. Throughout, I have tried to see the Lower Wye as half full, not half empty, for, despite the losses, we still have much to enjoy, and there are signs that some of the wildlife can hold its own. Moreover, interesting initiatives are afoot that offer some hope of partial recovery of what has been lost.