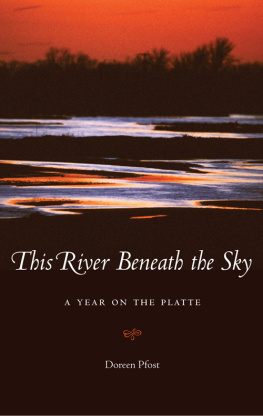

Doreen Pfosts personal homage to Nebraskas Platte River is a powerful collection of twelve essays encompassing a year, bounded by its spring crane migration. They reveal a Willa Catherlike affection for the place and its people and an Aldo Leopoldlike capacity to describe its wildlife, especially the iconic sandhill cranes.

Paul A. Johnsgard, author of Seasons of the Tallgrass Prairie: A Nebraska Year

Articulate and compelling.... Doreen Pfost elegantly weaves together the story of these magnificent ambassadors for things wild and free in a part of our planet that humans have transformed in recent centuries, but where ancient wildlife spectacles still happen.

This River Beneath the Sky

A Year on the Platte

Doreen Pfost

University of Nebraska Press | Lincoln and London

2016 by the Board of Regents of the University of Nebraska

Cover image Joel Sartore / joelsartore.com

Author photo courtesy of Erv Nichols

An earlier version of chapter 1 was previously published in Platte Valley Review, Fall 2009.

All rights reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Pfost, Doreen.

Title: This river beneath the sky: a year on the Platte / Doreen Pfost.

Description: Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015021583

ISBN 9780803276796 (paperback: alkaline paper)

ISBN 9780803285347 (epub)

ISBN 9780803285354 (mobi)

ISBN 9780803285361 (pdf)

Subjects: LCSH : Natural historyNebraskaPlatte River Valley. | LandscapesNebraskaPlatte River Valley. | Pfost, DoreenTravelNebraskaPlatte River Valley. | Nature observationNebraskaPlatte River Valley. | Nature writersNebraskaPlatte River ValleyBiography. | Platte River Valley (Neb.)Description and travel. | Platte River Valley (Neb.)Environmental conditions. | NatureEffect of human beings onNebraskaPlatte River Valley. | Nature conservationNebraskaPlatte River Valley. | BISAC : NATURE / Ecosystems & Habitats / Rivers. | NATURE / Animals / Birds. | HISTORY / United States / State & Local / Midwest ( IA , IL , IN , KS , MI , MN , MO , ND , NE , OH , SD , WI ).

Classification: LCC QH 105. N 2 P 43 2016 | DDC 508.782dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015021583

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

For Mark and Andrew

Contents

The story of the Platte River would be incomplete without the stories of people: those who live and work on the river and those who have felt the river do its work on them. I am grateful to the many people who shared their time and stories with me; some of their names appear in the text: Alan Bartels, Kenny Dinan, the late Charles Frith, Karine Gil, Deb Hann, the late Jack and Pat Hann, Carol Hines, Rita Johnson, Steve and Cyndi King, Ron Klataske, Gary Lingle, John Murphy, Ed and Sil Pembleton, and Kirk Schroeder. The recollections of several other people improved my understanding of Platte River conservation efforts. I am indebted to Bessie Frith, Gene Hunt, Marge and Bruce Kennedy, Glennis Nagel, Grant Newbold, Bill Taddicken, and the late Margaret Triplett. Thanks also to Joe Methe, who introduced me to Rita Johnson.

Earlier versions of chapters 1, 3, and 11, plus portions of chapters 2 and 9, were part of my 2008 masters thesis at University of NebraskaKearney, where I earned an MA in English with a creative-writing emphasis. I appreciate the guidance I received from my thesis committee: Barbara Emrys, Susanne Bloomfield, and Robert Murphy. In addition, Susanne introduced me to the Western Literature Association, which recognized Trailing Consequences a slightly abridged version of chapter 3 with the 2011 Frederick Manfred Award.

This book begins and ends at the National Audubon Societys Lillian Annette Rowe Sanctuary. I could not have written it without the help and encouragement I received from the staff and my fellow volunteers at Rowe. In particular, Keanna Leonard, Kent Skaggs, and Bill Taddicken have been there since I became a volunteer in 2005, and they have made me feel as if I have a home on the river.

Thanks most of all to my husband, Mark, and to my son Andrew for their understanding and support. This book is for them, with love.

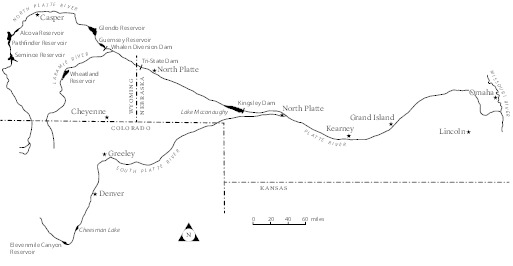

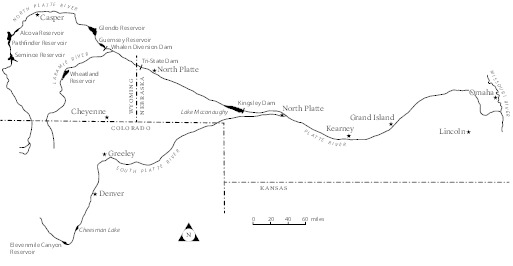

1. The North Platte and South Platte Rivers originate in the Rocky Mountains and meet in Nebraska to form the Platte River. U.S. Department of the Interior/U.S. Geological Survey.

Swept Up in a Wind-Borne River

March and Early April

Their voices arrive first. A distant, soft-edged trill rolls toward the quiet, gray river. Soon, a flock of birds, flying in a lazy V formation, materializes in the southern sky. As it flies closer, as the voices grow louder and sharper, each gray bird becomes distinct, its neck outstretched, legs trailing behind. I raise my binoculars and watch the slow sweep of wings, the upward flick of wingtips. After ten months absence and a daylong flight, two hundred sandhill cranes are announcing their return to the Platte River. Their voices rise in pitch and intensity as they approach, as if they were elated to be here at last. Or perhaps it is only I who am elated. The flock skims across the channel, toward the north-bank meadow. The V collapses as the birds cup their wings in six-foot arcs that tip, glide, and tip again, while cranes fall like pattering rain.

This is how spring arrives at the Platte not with the flip of a calendar page, but from little clouds blown in on a southerly wind. The first sprinkles began weeks ago, but by early March every day ends in a steady shower of cranes.

A second bugling flock glides into view, then a third. Then more. And more. Flocks coming in from the south are new arrivals. Others approach from north and west, from cornfields where they have been feeding since morning. They drift down to the meadow, smooth as smoke; just before they drop out of sight behind the streamside brush, the pale undersides of their wings flash golden in the late-afternoon light.

The sun sinks lower in the sky; all around, black tendrils appear to be rising from the horizon, interweaving, drifting nearer, converging on the river. Flocks of Canada geese and white-fronted geese trade back and forth above me, in search of an evening roost. Meanwhile, cranes continue pouring by the hundreds into the north meadow. Now come the snow geese three hundred, four hundred, a thousand in a glittering web that unravels across the sky. Bugles, honks, and squeaks blend in a steady, low-level din that washes across the river. Each passing flock sounds like a wind gust that swells to a roar as it approaches and then fades away.

Twisting clouds of cranes begin to rise from the meadow. They swirl for several seconds and fill the air with piercing bugles. The cranes spill down in waves, landing first on sandbars and then wading into the water to make way for those who follow.

A great roar rises downstream, and within moments the sky is churning with dark and white geese, up above, all around, swarming toward the sunset. Above the wading cranes, a fluttering gray and white blizzard of ten thousand geese piles up, hundreds of feet in the air. An invisible floor slides out from under them, and they drop down, filling the river, obscuring the water.