THE SOUL

OF AN

INDIAN

N EW W ORLD L IBRARY

N OVATO, C ALIFORNIA

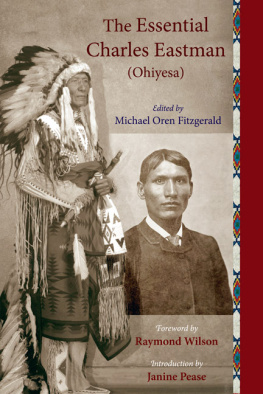

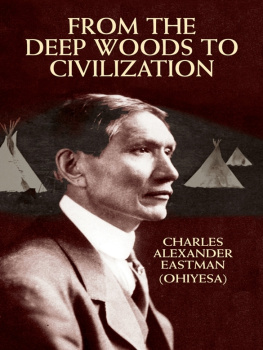

Based primarily on The Soul of the Indian 1911 Charles Alexander Eastman, with additional material, all Charles Alexander Eastman; Indian Boyhood 1922; From the Deep Woods to Civilization 1916; Old Indian Days 1907; Indian Scout Talks: A Guide for Boy Scouts and Camp Fire Girls 1914; The Indian To-day; The Past and Future of the First Americans 1915.

This edited version copyright 1993, 2001 by Kent Nerburn Cover design by Alexandra Honig

All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, or transmitted in any form, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review; nor may any part of this book be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or other, without written permission of the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Eastman, Charles Alexander, 18581939

The soul of an Indian and other writings from Ohiyesa

(Charles Alexander Eastman) / edited and arranged by Kent Nerburn

p. cm.

A reconfiguration of his [i.e., Eastmans] writings, chosen from a variety of sources, woven together in a way that gives voice to the spiritual vision that animated all his writing and speaking.

ISBN 1-57731-200-7 (alk. paper)

1. Indians of North America Religion and mythology. 2. Santee Indians Religion and mythology. 3. Indians of North America Social life and customs. 4. Santee Indians Social life and customs. 5. Eastman,

Charles Alexander, 18581939.

I. Nerburn, Kent, 1946 II. Series

E98.R3E148 1993

299.7 dc20

9324678

CIP

First printing, October 2001

ISBN 1-57731-200-7

Printed in Canada on acid-free, recycled paper Distributed to the trade by Publishers Group West

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

When you see a new trail, or a footprint you do not know, follow it to the point of knowing.

Uncheedah, the grandmother of Ohiyesa

CONTENTS

I t is my goal in this book to bring before you the thoughts of one of the most fascinating and overlooked individuals in American history: Ohiyesa, also known by the Anglicized name of Charles Alexander Eastman.

Ohiyesa was, at heart, a poet of the spirit and the bearer of a spiritual vision. To the extent that he dared, and with increasing fervor as he aged, he was a preacher for the native vision of life. It is my considered belief it is his spiritual vision, above all else, that we of our generation need to hear. We hunger for the words and insights of the Native American, and no man spoke with more clarity than Ohiyesa.

Ohiyesa was born in southern Minnesota in the area now called Redwood Falls in the winter of 1858. He was a member of the Santee tribe of the Dakota, or Sioux, nation. When he was four, his people rose up in desperation against the U.S. government, which was systematically starving them by withholding provisions and payment they were owed from the sale of their land.

When their uprising was crushed, more than a thousand men, women, and children were captured and taken away. On the day after Christmas in 1862, thirty-eight of the men were hanged at Mankato, Minnesota, in the greatest mass execution ever performed by the U.S. government. Those who were not killed were taken to stockades and holding camps, where they faced starvation and death during the icy days of the northern winter.

Ohiyesas father, Many Lightnings, was among those captured.

Ohiyesa, who was among those left behind, was handed over to his uncle to be raised in the traditional Sioux manner. He was taught the ways of the forest and the lessons of his people. He strove to become a hunter and a warrior. Then, one day while he was hunting, he saw an Indian walking toward him in white mans clothes. It was his father, who had survived the internment camps and had returned to claim his son.

During his incarceration, Many Lightnings had seen the power of the European culture and had become convinced that the Indian way of life could not survive within it. He despised what he called reservation Indians who gave up their independence and tradition in order to accept a handout from the European conquerors.

He took Ohiyesa to a small plot of farming land in eastern South Dakota and began teaching him to be a new type of warrior. He sent him off to white schools with the admonition that it is the same as if I sent you on your first warpath. I shall expect you to conquer.

Thus was born Charles Alexander Eastman, the Santee Sioux child of the woodlands and prairies who would go on to become the adviser to presidents and an honored member of New England society.

Ohiyesa, or Eastman, went to Beloit College where he learned English and immersed himself in the culture and ways of the white world. Upon graduation he went east. He attended Dartmouth College, then was accepted into medical school at Boston University, which he completed in 1890. He returned to his native Midwest to work among his own people as a physician on the Pine Ridge reservation, but became disenchanted with the corruption of the U.S. government and its Indian agents. After a short-lived effort to establish a private medical practice in St. Paul, Minnesota, he turned his focus back to the issue of Indian-white relations.

For the next twenty-five years, he was involved in various efforts to build bridges of understanding between the Indians and non-Indian people of America. He worked first for the YMCA, then served as an attorney for his people in Washington, then returned to South Dakota to spend three years as physician for the Sioux at Crow Creek.

In 1903 he went back to Massachusetts and devoted himself to bringing the voice of the Indian into the American intellectual arena. He became deeply involved in the Boy Scout program, believing it was the best way to give non-Indian American youth a sense of the wonder and values that he had learned growing up in the wild.

Eventually, with the help of his wife, he established a camp of his own in New Hampshire in which he tried to re-create the experience of Sioux education and values for non-Indian children.

But financial troubles and the fundamentally irreconcilable differences between Indian culture and white civilization ultimately took their toll. In 1918 he and his white wife separated, and in 1921 he left New England for good. He continued to believe that the way of civilization was the way of the future, but he had lost much of his faith in its capacity to speak to the higher moral and spiritual vision of humanity. He returned again to his native forests of the Midwest, devoting more time to his traditional ways, often going into the woods alone for months at a time.

OF AN

OF AN