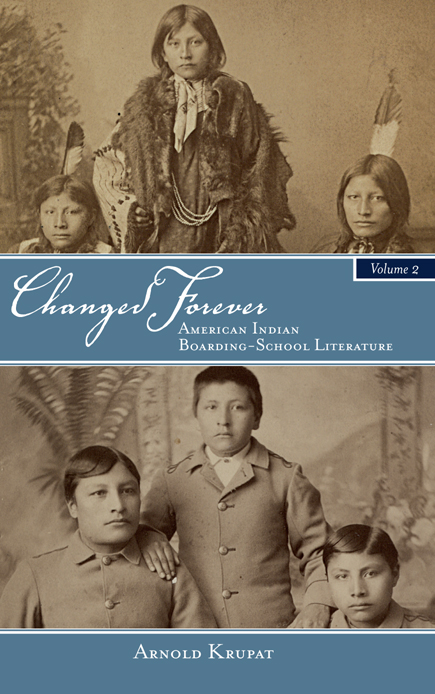

On the cover: Chauncey Yellow Robe (Timber), Henry Standing Bear, and Richard Yellow Robe (Wounded) at the time they entered Carlisle Indian School in 1883 and three years later, in 1886, both photographs taken by John N. Choate. Courtesy of Dickinson College Carlisle Indian School Project.

Published by State University of New York Press, Albany

2020 State University of New York

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

For information, contact State University of New York Press, Albany, NY

www.sunypress.edu

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Krupat, Arnold, author.

Title: Changed forever: American Indian boarding-school literature. Volume II / Arnold Krupat. Other titles: American Indian boarding school literature

Description: Albany, NY : State University of New York Press, [2020] | Series: SUNY series, Native traces | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017022009 (print) | LCCN 2018005523 (ebook) | ISBN 9781438480084 (e-book) | ISBN 9781438480077 (hardcover : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Off-reservation boarding schoolsUnited StatesBiography. | Boarding school studentsUnited StatesBiography. | Indian studentsUnited StatesBiography. | Hopi IndiansBiography. | Navajo IndiansBiography. | Apache IndiansBiography. | AutobiographiesIndian authors.

Classification: LCC E97.5 (ebook) | LCC E97.5.K78 2018 (print) | DDC 371.829/97dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017022009

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Gerald VizenorWhat has become of the thousands of Indian voices who spoke the breath of boarding-school life?

K. Tsianina Lomawaima

We still know relatively little about how Indian school children themselves saw things.

Michael Coleman

Boarding-school narratives have a significant place in the American Indian literary tradition.

Amelia Katanski

INTRODUCTION

FROM THE MOMENT THEY SET FOOT UPON THESE SHORES, THE EUROPEAN invader-settlers of America confronted an Indian problem. This consisted of the simple fact that Indians occupied lands the newcomers wanted for themselves. To be sure, this was not the case for the earliest Spanish invaders of the Southeast and Southwest in the mid-sixteenth century, whose intent was to find treasure and to convert and missionize the tribal peoples they encountered. But in the Northeast, the English, from the early seventeenth century, and then the Americans, as they made their way across the continent, came to understand that broadly speaking, Americas Indian problem permitted only two solutions: extermination or education. Extermination was costly and dangerous, and in time it came to be thought wrong.

It then began to appear wiser, as the title of Robert Trennerts introduction to a study of the Phoenix Indian School put the matter, for policymakers to proceed according to the assumption that The Sword Will Give Way to the Spelling Book (1988 3), thus offeringagain to cite Trennertan alternative to extinction (1975). Educating Native peoplesteaching them to speak, read, and write English; to convert to one or another version of Christianity; and to accept an individualism destructive of communal tribalism, ethnocide rather than genocide, was a strategy that might more efficiently and with fewer pangs to the national conscience free up Native landholdings and transform the American Indian into an Indian-American, uneasily inhabiting if not quite melted into the broad pot of the American mainstream.

In a fine 1969 study, Brewton Berry remarked that so far as the choice between coercion and persuasion was concerned (23), Formal education has been regarded as the most effective means of bringing about assimilation (22). In these respects, Trennert writes, when the Phoenix Indian School was founded in 1891, it was for the specific purpose of preparing Native American children for assimilation to remove Indian youngsters from their traditional environment, obliterate their cultural heritage, and replace that with the values of white middle-class America. Complicating the Further complicating it well in to the 1960s and beyond was the fact that white middle-class America was not generally willing to accommodate persons of color regardless of whether they shared its values or not.

In the Annual Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs for 1890, the Rules for Indian Schools stated clearly that the government, in organizing this system of schools, intended them to be preparatory and temporary; that eventually they will become unnecessary, and a full and free entrance be obtained for Indians into the public school system of the country. It is to this end, the Rules continued, that all officers and employees of the Indian school service should work (in Bremner 1971, 2: 1354). Although Native Americans could obtain a full and free entrance to all public schools in the United Statesas African Americans could noton those occasions when they availed themselves of that right, they were not always welcomed or well served. Indeed, as Wilbert Ahern has written, The local public schools to which 53% of Indian children went in 1925, were even less responsive to Indian communities than the BIA schools (1996 88). And some of the Indian Offices Catholic schools, from about the 1880s through the 1960s, as we will see, provided their own particular forms of disservice to their Native students.

In her study of the St. Josephs Indian boarding school in Kashena, Wisconsin, Sarah Shillinger affirms that Assimilation was an important, if not a more important goal than education to the supporters of the boarding-school movement (2008 95). Her conclusion, however, is that the boarding schools results were closer to an integration of both cultural systems [Indian and white] than to assimilation into Euro-American society (115, my emphasis). This seems to me accurate, and I will quote other writers on the subject who state roughly similar conclusions in different ways. But the degree to which any single individual could successfully integrate both cultural systems, and what it meant to her to do so, varied a good deal. As we will see, some boarding school students had little trouble living in two worlds, as the metaphor is often givena metaphor that is usually unexamined. Others found the two cultural systems, Native and settler, to be substantially in conflict, so that bridging the gapanother largely unquestioned metaphorwas painful and difficult. Further complicating the matter is the fact that one of the cultural systems was backed by the overwhelming power of the colonial state.

By the turn of the twentieth century, as David Adams has written, Those responsible for the formulation of Indian policy were sure of one thing: the Indian could not continue to exist as an Indian. Indian people, therefore, had to choose between civilization or extinction (1995 28), and in order to become civilized, Indians needed to be educated. By the early 1890s, according to Ahern, Thomas Jefferson Morgan, commissioner of Indian affairs, had designed the means to extinguish American Indian cultures by going after the children, pulling them from their homes, and indoctrinating them with American civilization (1996 88). To cite Adams once more, The boarding school, whether on or off the reservation, was the institutional manifestation of the governments determination to completely restructure the Indians minds and personalities (1995 97). As Superintendent Cora Dunn of the Rainy Mountain School said in 1899, Our purpose is to change them forever (in Ellis 1996b xiii). I have adapted her words for the title of this book.