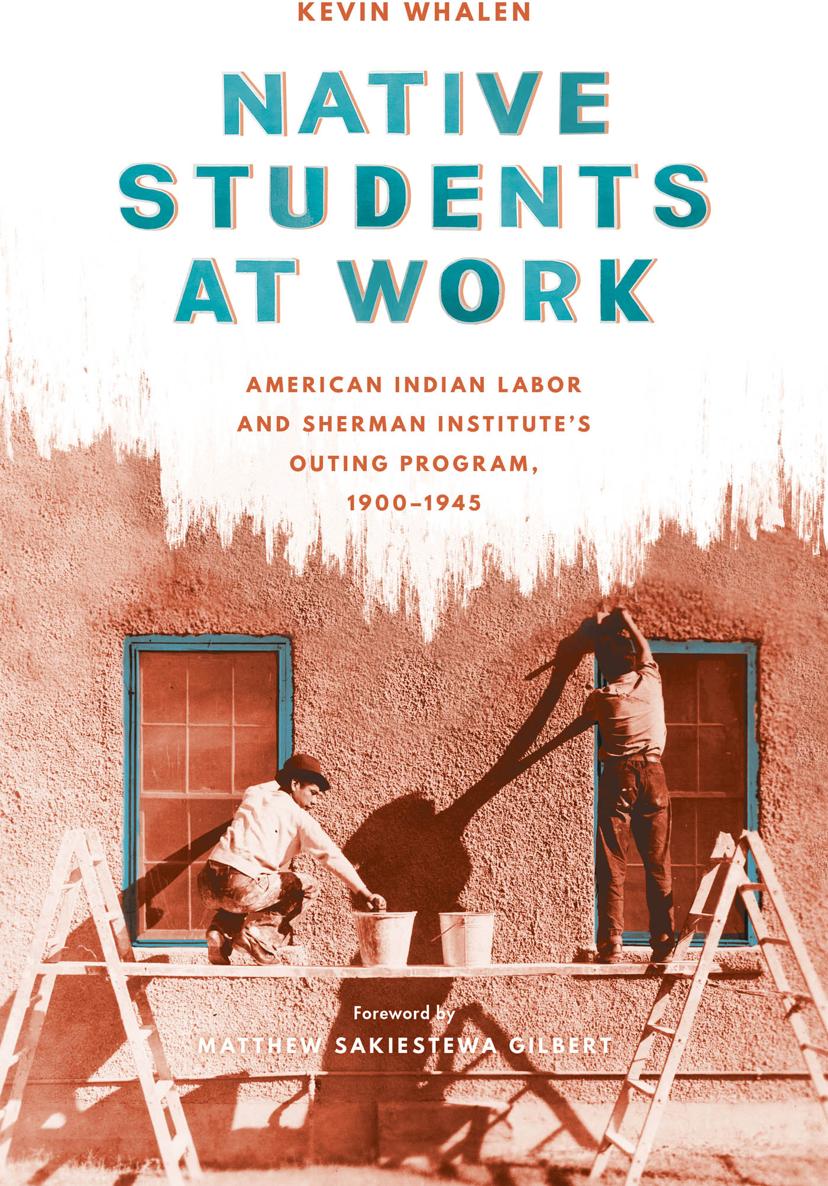

Charlotte Cot, Matthew Sakiestewa Gilbert, and Coll Thrush, Series Editors

NATIVE

STUDENTS

AT WORK

American Indian Labor and

Sherman Institutes

Outing Program, 19001945

KEVIN WHALEN

Foreword by Matthew Sakiestewa Gilbert

2016 by the University of Washington Press

Printed and bound in the United States of America

Composed in Charter, a typeface designed by Matthew Carter

20 19 18 17 16 5 4 3 2 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or

transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical,

including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval

system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON PRESS

www.washington.edu/uwpress

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Whalen, Kevin, author.

Title: Native students at work : American Indian labor and Sherman

Institutes Outing Program, 19001945 / Kevin Whalen ; foreword by Matthew Sakiestewa Gilbert.

Other titles: American Indian labor and Sherman Institutes Outing Program, 19001945

Description: Seattle : University of Washington Press, [2016] | Series: Indigenous confluences | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016002211 | ISBN 9780295998268 (hardcover : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Sherman Institute (Riverside, Calif.)History. | Off-reservation boarding schoolsCaliforniaRiversideHistory. | Indian studentsCaliforniaRiversideHistory20th century. | Indian studentsCaliforniaLos Angeles RegionEmployment. | Indian studentsCalifornia, SouthernSocial conditions20th century. | Indians of North AmericaEmploymentCaliforniaLos Angeles RegionHistory20th century. | Women household employeesCaliforniaLos Angeles RegionHistory20th century. | Agricultural laborersCalifornia, SouthernHistory20th century. | Indians of North AmericaCalifornia, SouthernSocial conditions20th century. | Riverside (Calif.)History.

Classification: LCC E97.6.S54 W53 2016 | DDC 371.829/7079497dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2016002211

The paper used in this publication is acid-free and meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481984.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER 1 Labored Learning:

The Outing System at Sherman Institute

CHAPTER 2 Indian School, Company Town: Students from

Sherman Institute at the Fonatana Farms Company

CHAPTER 3 Into the City: Quechan and Mojave

Domestic Workers in Los Angeles

CHAPTER 4 Indians Should Not Go There:

The Great Depression and the End of Outing

CONCLUSION: Unthinkable Histories?

Native People, Bureaucracies, and Work

FOREWORD

Matthew Sakiestewa Gilbert

UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN

When I was working with Clifford Trafzer on an edited collection on Sherman Institute entitled The Indian School on Magnolia Avenue, he kept raving about a student named Kevin Whalen who was conducting research on the schools outing program. Cliff wanted me to consider including Kevins essay in our book, a chapter he had written entitled Labored Learning. Cliffs undying enthusiasm caused me to take special notice of Kevin and his work.

In the academy it is common for established scholars to guard turf and to be critical of others who do work in their area of research. All junior scholars experience this to some degree, and even I allowed this mentality to influence my initial thoughts about Kevin. Who was this star, as Cliff described him, and what more could he possibly add to what Iand othershave already done? While these were my initial reactions, my opinion quickly changed once I began reading Kevins essay. It took only a few pages into his chapter for me to realize that his work was too good, and his writing too polished, for me to deny that there was something special about him and his work. Needless to say, we added the young scholars chapter to our book.

In this book Kevin takes things even further, explaining how, at the beginning of the 1900s, officials at Sherman sent Native students off-campus to work as domestic servants, ranch hands, and many other occupations. He notes that school officials and local ranchers used the agricultural industry of Southern California to further U.S. government assimilation goals and to fill the regions labor needs, respectively. And he explores the reasons why Indian students agreedand often requestedto work beyond the school walls at places such as the Fontana Ranch and at the many citrus orchards in the greater Riverside area. Although I previously had written about Hopi students who participated in the schools outing program in my own book, Education beyond the Mesas, Kevin takes the conversation to a different level as he has now established himself as an authority on Sherman and Indian labor at off-reservation Indian boarding schools.

At the University of California, Riverside, under the mentorship of Cliff and Ojibwe historian Rebecca Monte Kugel, Kevin learned the importance of working with Native communities, and not just writing about them. Our professors taught us the value of contributing something useful to Indian tribes, and they urged us to consider how our research can benefit Native communities. The education that we received in Native history there was a combination of the theoretical and the practical. Familiarity with archives and the process of honing skills needed to analyze documents was only part of our training. Cliff and Monte also encouraged us to leave the comforts of campus and interact with and work alongside Native people. Kevin certainly experienced this; he regularly accompanied Cliff to community gatherings on and off Indian reservations in Southern California, including the Colorado River Indian Tribes. And he interviewed numerous individuals for his book, including the director of the Sherman Indian Museum, Lorene Sisquoc, and a former Sherman student, Galen Townsend, to name a few.

After Kevin finished at UC Riverside, he became my colleague at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and continued working on his book as a Chancellors Postdoctoral Fellow of American Indian Studies, where he gained additional valuable insights from our director, Robert Warrior, and other colleagues and students. Unfortunately, Kevin arrived right as a crisis was unfolding over the universitys improper de-hiring of an AIS faculty member. Although new to campus, Kevin proved he was a true ally by standing in solidarity with me and my colleagues as we protested the universitys decision and demonstrated our commitment to shared governance and academic freedom. Nobody expected Kevin to join the fight, but he eagerly engaged in the protests, and soon it became clear to all that our struggle had also become his struggle.

This book, then, has emerged from numerous spaces, and each of these spaces has influenced Native Students at Work in unique ways. They have all done their part to transform what started as a chapter of an edited collection into the present volume. Kevin will no doubt write other books. He may even one day write a second book on Sherman or some other aspect of Indian boarding schools. But for me, this book will always remain special. Not many scholars get an opportunity to help shepherd a project from its infancy to publication. I did just that, and throughout all of these challenges, I remain grateful to Kevin for allowing me to accompany him on this journey.