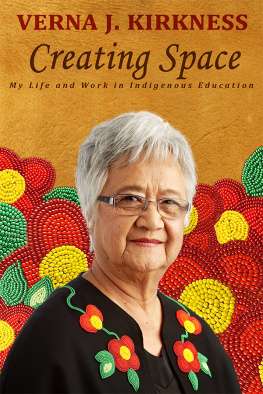

Marinella Lentis deftly lays out the terrain of Indian school art programs.... A significant contribution to the field, Colonized through Art clearly, succinctly, and broadly expands our knowledge of the ways government officials pushed assimilation through artnot to mention the resistance many Native students creatively expressed.

Linda M. Waggoner, author of Fire Light: The Life of Angel De Cora, Winnebago Artist

Colonized through Art

American Indian Schools and Art Education, 18891915

Marinella Lentis

University of Nebraska Press | Lincoln and London

2017 by the Board of Regents of the University of Nebraska

Cover designed by University of Nebraska Press; cover images are from the interior.

Author photo courtesy of the author.

Portions of chapter 2 previously appeared as Art for Assimilations Sake: Indian-School Drawings in the Estelle Reel Papers, American Indian Art Magazine 38, no. 5 (Winter 2013): 4451.

All rights reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Lentis, Marinella, author.

Title: Colonized through art: American Indian schools and art education, 18891915 / Marinella Lentis.

Other titles: American Indian schools and art education, 18891915

Description: Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016034818 (print)

LCCN 2016049456 (ebook)

ISBN 9780803255449 (cloth: alk. paper)

ISBN 9781496200686 (epub)

ISBN 9781496200693 (mobi)

ISBN 9781496200709 (pdf)

Subjects: LCSH : Indians of North AmericaEducationHistory. | ArtStudy and teachingUnited StatesHistory. | Indians of North AmericaVocational educationUnited StatesHistory. | Indians of North AmericaCultural assimilationUnited States. | Off-reservation boarding schoolsUnited States.

Classification: LCC E 97 . L 48 2017 (print) | LCC E 97 (ebook) | DDC 371.8297dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016034818

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

To Doug, Elizabeth, Christopher, and Rikardo

My people are a race of designers.

I look for the day when the Indian

shall make beautiful things for all the world.

Angel DeCora

Contents

The idea for this project started many years ago in a graduate class on the history of American Indian education at the University of Arizona. I am thankful to all who have helped me and supported me along the way since that spring semester and who have witnessed the transformation of that original paper into my doctoral dissertation and, finally, into this book. First among them is my husband, Doug. I would not be the person I am today if it werent for him, and this work would have certainly not seen the light of day without his constant love and encouragement. My infinite thanks to you.

I want to thank Tsianina Lomawaima, Nancy Parezo, and Robert Williams for their patient guidance and advice, and for showing me what it means to be a scholar. I appreciate all they have done for me throughout the years, in and out of the classroom, in times of confidence and in times of need. I also want to express my gratitude to Matthew Bokovoy and the manuscript reviewers, especially Linda Waggoner, for believing in this project and encouraging me throughout, and to everyone at the University of Nebraska Press who has made this book possible.

Research for this book could have not been completed without the invaluable knowledge and assistance of many archivists in private and public repositories across the country. I want to thank in particular Randy Thompson and Debra Schultz at the National Archives and Records Administration, Riverside, California; Lorene Sisquoc at the Sherman Indian Museum and Archives; the entire staff of the New Mexico State Records Center and Archives; the archivists at the Center for Southwest Research at the University of New Mexico; Diane Bird at the Laboratory of Anthropology; Dave Miller at the National Archives and Records Administration, Denver, Colorado; Ken House at the National Archives and Records Administration, Seattle, Washington; Jane Davey at the Northwest Museum of Arts and Culture; Leanda Gahegan at the National Anthropological Archives; Jim Gerencser at Dickinson College; and everyone at the Still Pictures Division at the National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, Maryland. I am particularly grateful to Leigh Kuwanwisiwma of the Hopi Cultural Preservation Office for allowing me to publish the kachina drawings included in this volume and to Anna Harbine (Northwest Museum of Arts and Culture), Daisy Njoku (National Anthropological Archives), and Claire-Lise Benaud (Center for Southwest Research) for promptly answering my requests and granting permissions.

I am indebted to those organizations that provided me with financial support so that I could travel to conduct the necessary archival research: the New Mexico Office of the State Historian, the Arizona Archaeological and Historical Society, the Historical Society of Southern California, the Association of Women Faculty at the University of Arizona, the Charles Redd Center for Western Studies, and the Graduate Interdisciplinary Programs at the University of Arizona. My appreciation also goes to Michael Spinella and the Text and Academic Authors Association for their assistance with publication costs.

Last, but not least, I want to thank my family and friends: those who are abroad in my homeland, those who are physically far from me but close to my heart, those who have made us feel at home in the South, and those who have always had confidence in me and my ideas.

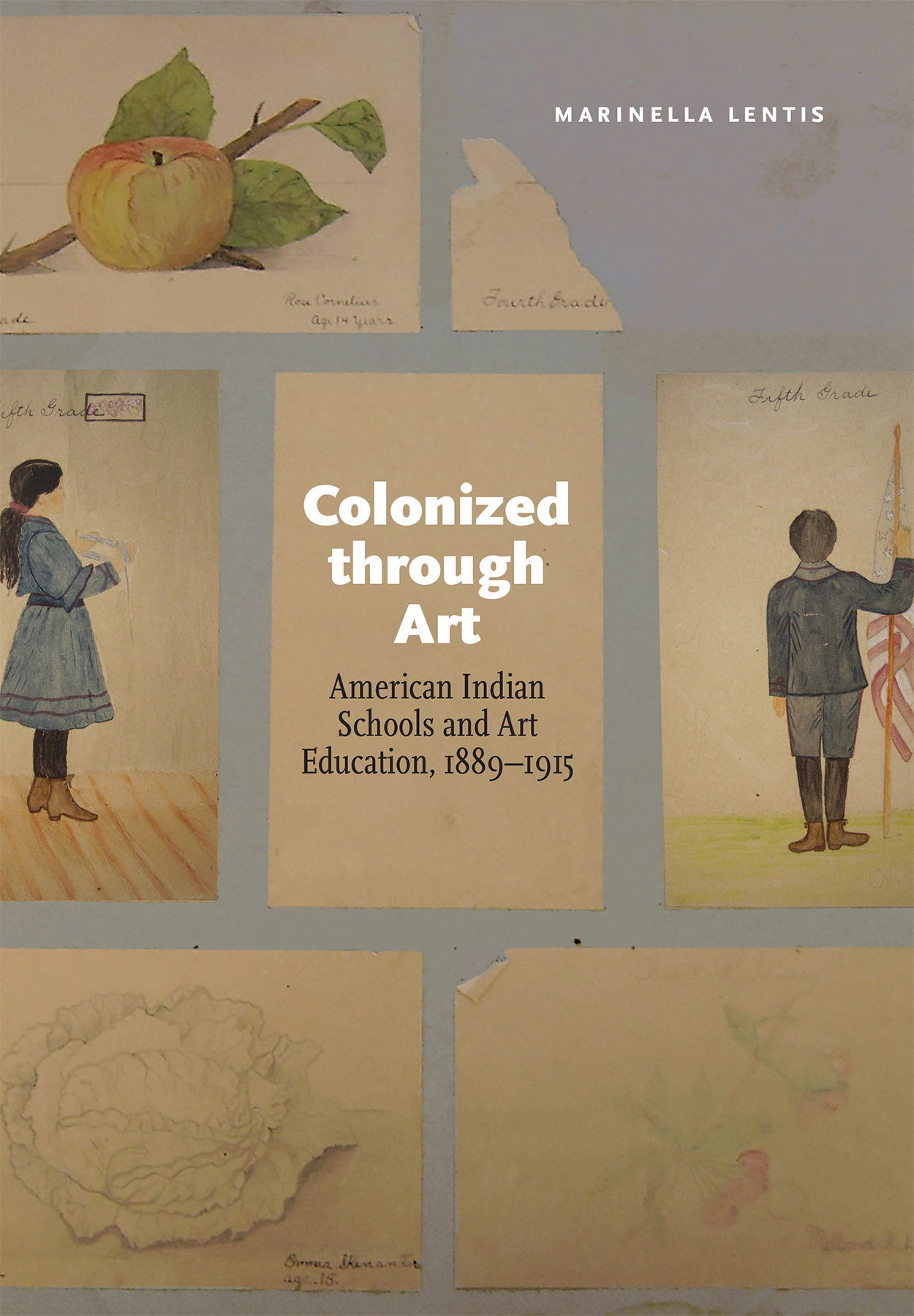

Every child enjoys drawing with colored pencils, crayons, and markers and putting on paper his ideas about the world around him. Similarly, children love to touch and feel things with their own hands, give shape to something out of nothing, to build, to invent. Her mind directs her hand into spontaneous compositions that sooner or later are going to reflect the environment in which she grows and through which she learns about reality. But when such natural and imaginative instincts are forcibly rectified and redirected toward what someone outside of the childs circle deems more correctthe right imageries, the right shapes, the more appropriate color and usagesomething is inevitably lost. In the childs mind, a door that was once open to uncountable possibilities of exploration, experience, and knowledge is now all of a sudden closed, although not permanently locked. This unnatural imposition no longer allows the young person to grow and develop to his or her full potential, because the pleasurable creative act has now become an oppressive instrument for reshaping the world according to a different set of foreign and unfamiliar standards that do not value the individuals own imagination, background, and heritage. This is the art training American Indian children received in government schools at the turn of the twentieth century. The purpose and content of that kind of training are the subjects of this book.

The establishment of boarding schools for American Indian children at the end of the nineteenth century marked the beginning of a systematized, government-sanctioned process of assimilation of the Indigenous With the proper kind of education, Indian boys and girls could learn to live and work like Anglo-Americans and thus advance from their primitive state to a civilized one.