This study of the Flandreau and Pipestone Indian Schools is important because it covers the two schools in great depth while also linking various historical contexts and periods. The book will appeal to both scholars in the field and to descendants of the schools students. I especially appreciate Landrums inclusion of the specter of race science regarding student evaluations at the schools. She also has further clarified and added greater nuance to the discussion of the Puritan praying towns and provided a valuable discussion of the self-pedagogy of the Five Civilized Tribes.

Hayes P. Mauro, associate professor of art and design at CUNY s Queensborough Community College and author of The Art of Americanization at the Carlisle Indian School

Landrums work provides thorough institutional histories of the Flandreau and Pipestone boarding schools and explains how changing federal Indian policies impacted those who taught, administered, and attended them. She also includes a collection of personal reflections, some heartbreaking and some uplifting, by those who passed through those schools.

Tim Garrison, professor of history at Portland State University and coeditor of The Native South: New Histories and Enduring Legacies

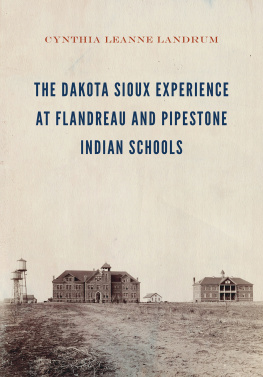

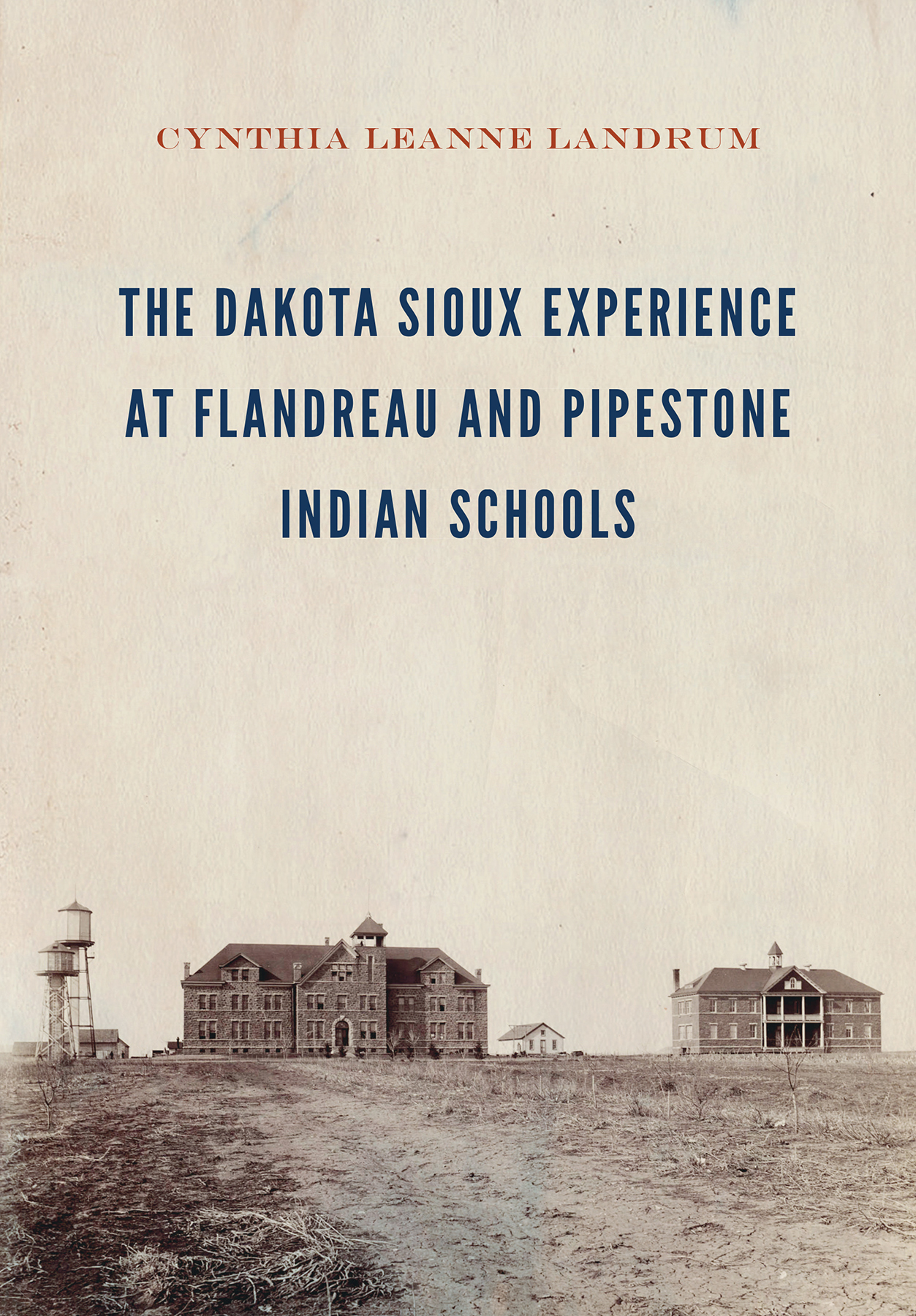

The Dakota Sioux Experience at Flandreau and Pipestone Indian Schools

Cynthia Leanne Landrum

University of Nebraska Press | Lincoln and London

2019 by the Board of Regents of the University of Nebraska.

Cover designed by University of Nebraska Press; cover image of Pipestone Indian Training School campus, courtesy of the Pipestone County Historical Society.

All rights reserved.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Landrum, Cynthia, 1967 author.

Title: The Dakota Sioux experience at Flandreau and Pipestone Indian schools / Cynthia Leanne Landrum.

Description: Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018017432

ISBN 9781496212078 (cloth: alk. paper)

ISBN 9781496213532 (epub)

ISBN 9781496213549 (mobi)

ISBN 9781496213556 (pdf)

Subjects: LCSH : Dakota IndiansEducation. | Flandreau Indian School (S.D.)History. | Pipestone Indian Industrial Training SchoolHistory.

Classification: LCC E 99. D 1 L 255 2019 | DDC 371.829/975243dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018017432.

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

This book is dedicated to the memory of Dr. Leonard Bruguier (Yankton Dakota Sioux) and to the people who live quietly and keep the ceremonies in the Upper Midwest.

Contents

On an early morning in March 1994 Ce Ce Big Crow (Oglala Lakota Sioux and older sister of SuAnne Big Crow) appeared at my door. She was dressed for the day and already had her roommate Wannette Wells (Dakota Sioux and a direct descendant of Chief Struck by the Ree) in the car as her first passenger. I was to be her second. I tried to protest because of too much work with my MA program in American Indian history at the University of South Dakota, where I was studying under Dr. Leonard Bruguier (Dakota Sioux and a direct descendant of Chief Struck by the Ree and Chief War Eagle) and Dr. Herbert T. Hoover (Ioway descent), but she would not listen. Within the space of an hour I was showered, dressed, and sitting in the back seat of her red Dodge Shadow. After we picked up our friend Albert Wright (Dakota Sioux), we quickly left Vermillion and headed north on the interstate.

At one point I asked her where we were going, and she said, A powwow. We are going to a powwow at Flandreau Indian School. We were all students at the University of South Dakota, but I was the only one in the car who was not a Lakota, Nakota, or Dakota Sioux Indian from Pine Ridge, Crow Creek, or Lower Brule Indian reservations. I was their token twenty-something ostensibly white friend from the East, whom they took to parties, powwows, dance clubs, punk/hardcore shows, and home to their respective reservations at the drop of a hat. As we drove in the sub-zero temperatures, the horizon was cleanly divided between the all pervasive snow and the blue mid-morning sky that unfolded like an amphitheater of sunshine and grain silos.

With the Red Hot Chili Peppers playing on the radio, the conversation drifted from classes and professors to the night before and back again, when Wannette suddenly said, I wonder what it looked like when there were no roads, just tipis, buffalo, and snow. This comment was followed by silence. Within the space of a few hours we arrived at Flandreau Indian School just in time for the afternoon Grand Entry.

As I sat in the bleachers with our coats, purses, and backpacks, my friends milled about and occasionally stopped back by to visit in order to introduce me to a friend of a friend or a cousin, within the space of a few hours. Visually it was a sea of feathers, jingle dresses, cedar, sage, and a lot of stop and go as the drumming continued and the prayers circumnavigated the room. And as the voices raced higher and louder, it seemed as though the ceiling opened up to reveal the night sky with its full illumination of planets and stars at the onset of their evening rotations.

It was at this moment that I realized I was surrounded by the descendants of the people whose names I had first encountered on the labels of storage units, catalogue cards, and objects two years earlier at the National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, when I was employed as a museum technician under the Anthropology Department. At the close of the nineteenth century individuals such as James Mooney and John Wesley Powell had traveled to the West, under the auspices of the Bureau of Ethnology, Geological Survey, or Smithsonian Institution and collected the material objects of the ancestors of the people in this arena. The objects obtained over time included Ghost Dance shirts (taken from the Wounded Knee Massacre site), medicine bundles, cradle boards, beaded bags, headdressesas I processed the objects that had been collected and shipped east, I wondered what had happened to the Dakota Sioux people after they had been scattered or placed on reservations, beginning with the treaties of Prairie du Chien (182530) and Mendota and Traverse de Sioux (1851).

As I looked around the auditorium and watched the descendants of the Yankton, Mdewakanton, Wahpeton, Wahpekute, and Sisseton (among others) fill the space, I realized that the lives of the Dakota people had been altered but not changed to the point where they had simply vanished into the ether of the dominant society or been removed south to Indian Territory. Further, I realized that federal institutions such as Flandreau and Pipestone Indian Schools were constructed in the 1890s as points of contact, which simultaneously provided a tribal identity and a form of autonomy in their homeland at two locations that were within close proximity to one of their most sacred sites, Pipestone.

All this slowly passed through my mind, as I watched the multicolored feathers flicker about with the beating of the drum and the singing of the songs that emanated from the Upper Midwest. As I sat in the bleachers I sensed that in this arena, for this moment in time, this was sacred ground, and time and space operated differently here than elsewhere. And within the space of a few hours, the people and the collective spiritual pulse would vanish into their cars, vans, and pickups as if this powwow had never happened, only to meet again at a later date for a similar ceremony at a location as potentially ironic as an off-reservation federal boarding school in Dakota Sioux Country.

Next page