ONLY A FOOT WOULD BE VISIBLE TO THE ENEMY

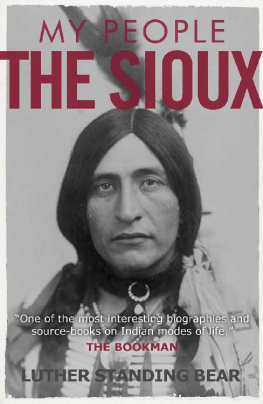

1931 by Luther Standing Bear

renewed 1959 by May M. Jones

Introduction 2006 by Delphine Red Shirt

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

First Bison Books printing: 1988

Reprinted by arrangement with Dolores Miller Nyerges and Anita

Miller Melbo

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Standing Bear, Luther, 1868?1939.

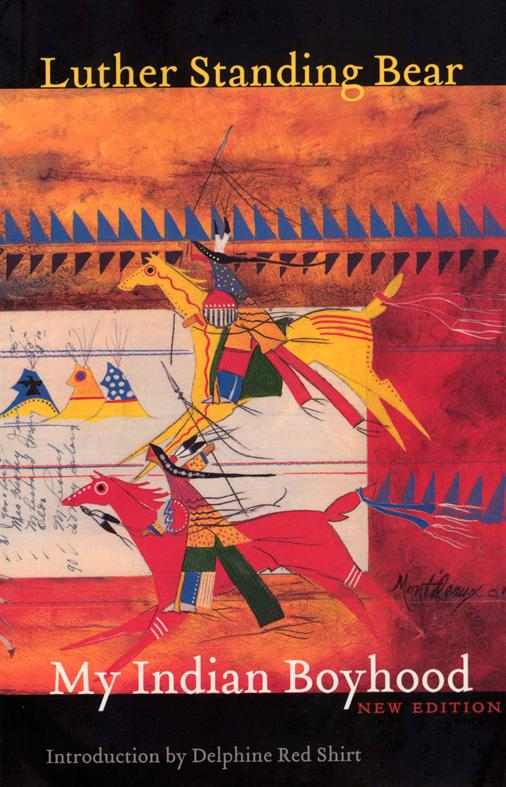

My Indian boyhood / Luther Standing Bear; with illustrations by

Rodney Thomson; introduction to the Bison Books edition by Delphine Red Shirt.New ed.

p. cm.

ISBN-13: 978-0-8032-9362-5 (pbk.: alk. paper)

1. Standing Bear, Luther, 1868?-1939. 2. Teton Indian]sKings and rulersBiography. 3. Indians of North AmericaGreat PlainsBiography. 4. Teton IndiansSocial life and customs. 5. Indians of North AmericaGreat PlainsSocial life and customs. I. Title.

E99.T34S72 2006

978.004'9752440092dc22 2006017817

[B]

E-book ISBN: 978-0-8032-9367-0

INTRODUCTION

DELPHINE RED SHIRT

Originally published in 1931, My Indian Boyhood was initially written for "the boys and girls of America." However, it is easily read and appreciated by anyone who wishes to learn about the Oglala Lakota way of life. Reader expectations are satisfied through text replete with ethnographic detail about the prereservation life of the Oglala Lakota people. With description that only one who grew up in the Lakota society and culture can impart, Luther Standing Bear tells his story.

Standing Bear grew up on the plains of North and South Dakota during a difficult transitional period for the Oglala Lakota. They were part of a major division of the Teton Sioux Nation residing in the Western Plains region of the United States. In a series of three treaties signed in 1824, 1851, and 1868 (the year Standing Bear was born), the U.S. government fully recognized the Oglala Lakota Nation as a domestic dependent sovereign residing within what was called Indian Country. Prior to these treaties, the boundaries of the Great Sioux Reservation enclosed all of South Dakota west of the Missouri River. By 1889 the U.S. government, through an act of Congress, had established five separate reservations for the Teton Sioux Nation, including the Pine Ridge Reservation that Standing Bear, by then a young adult, would call home.

Throughout My Indian Boyhood, Standing Bear keeps the name given to him by his family, Ota K'te. Lakota children are named at birth by their parents or by close relatives. Standing Bear's brothers' names, Sorrel Horse and Never Defeated, signified brave deeds that their father had been known for: he once had a sorrel horse shot out from under him, and he displayed heroic characteristics in battle, causing the people to remember him as never having been defeated. As Standing Bear later recalled, "In the names of his sons, the history of [my father] is kept fresh." Standing Bear's father was a leader who killed many to protect his people. Thus, like his brothers, Ota K'te (Plenty Kill) was also given a name that held significance.

Ota K'te kept his boyhood name until it changed to Mato Najin, or "Standing Bear," later in his life, according to Lakota custom. In the old tradition, he would have earned a new name through a heroic or brave deed, but by the time he reached an age when he could prove himself worthy, the Lakota people had been confined to the Pine Ridge Reservation. He took his father's name, Standing Bear, and at Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, he took the name Luther.

Standing Bear also had three sisters, Feather Weaver, Two Staffs, and Yellow Bird. Feather Weaver's name signified the many feather decorations her father owned. He also owned two staffs adorned with feathers, which had been given to him by the two lodges he was a member of, so he named Two Staffs after this honor. Yellow Bird's name was given to her by an aunt close to the family, and the girl would keep it always, just as her sisters would keep their names that honored their father. Unlike the boys in the family, the girls, once named at birth, kept their names throughout their lives.

Ota K'te establishes his identity as a Lakota boy of the Oglala Sioux early in his autobiography. "I was born a Lakota," he states in the beginning of the story of his childhood. Indeed, he was born into a strong, traditional familyhis father was a leader, described as "brave and dignified"; his mother, like many Lakota women, he describes as "quiet and gentle." Ota K'te was welcomed into this family and cherished, as most Lakota children are in a traditional home. He notes how Lakota parents "did not believe in whipping and beating children," a comment that is poignant in light of his later experiences at Carlisle Indian Industrial School.

In My Indian Boyhood Standing Bear mentions nothing of what lies ahead for the Lakota wakanja. Wakan refers to what is sacred, so children (wakanja) are seen as "sacred small beings" and treated thus, a belief that is firmly rooted in cause and effect. The people believed strongly in the fair treatment of children, who, like the elders completing the circle and physically returning to youth, needed protection, and that life would treat one according to how one treated a child. As the first son of a chief, Ota K'te knew his extra special status early on and enjoyed his father's attention.

The first lessons taught to a Lakota boy were trapping and catching game, not for sport, but for survival. For a young boy, this meant being able to throw a stone swiftly and with correct aim so that he could kill small game for food. When a young Lakota boy finally learned to make his first bow and set of arrows, Standing Bear acknowledges, is when "serious training began for the boy." Ota K'te's education began when his father tied Ota K'te's pony to his horse and taught the boy to ride properly. All the things a Lakota boy learned to survive in a harsh worldhorsemanship, hunting, fishinghe learned through play and games and observing the adults and natural world around him.

Standing Bear wrote My Indian Boyhood when he was sixtythree. The fullness of the story of his early life comes from Standing Bear's mature perspective as a Lakota elder telling childhood stories about Ota K'te in the oral tradition to a receptive audience. This rich tradition requires the speaker to not only entertain but also very often to teach practical life skills as well as Lakota epistemology. Standing Bear does this exceptionally well; even though he uses English, he accomplishes what he sets out to do as a Lakota elder giving voice to a living culture and teaching in the process.

In My Indian Boyhood Standing Bear focuses primarily on a childhood far from the change that was rapidly approaching the Oglala Lakota. In many ways, it represents a paradise lost. The Oglala Lakota leader Crazy Horse fought Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer and the Seventh Cavalry at the Battle of the Little Bighorn in 1876 when Standing Bear was eight years old, but his childhood was spent seemingly far from the war with the encroaching wasitu (whites). Victory at the Little Bighorn did not mean a better life for the Lakota. Instead, drastic changes occurred as events culminated in 1890, when the same Seventh Cavalry opened fire on a band of the Teton Nation at Wounded Knee, where approximately three hundred unarmed Lakota men, women, and children died on a bitterly cold winter morning in December of 1890.