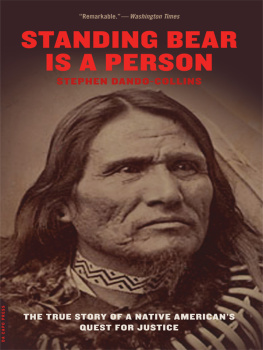

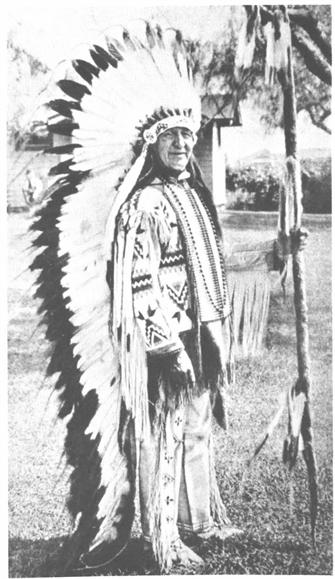

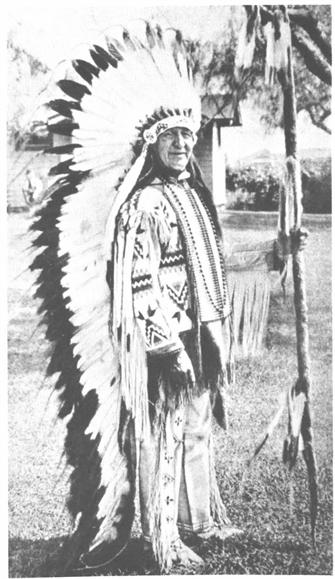

CHIEF STANDING BEAR IN FULL REGALIA

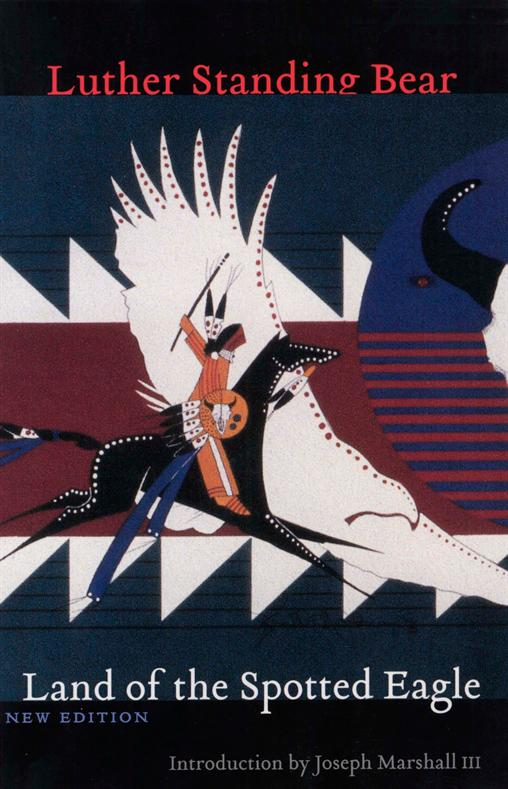

1933 by Luther Standing Bear

Renewal copyright, 1960, by May Jones

Foreword 1978 by the University of Nebraska Press

Introduction to the new Bison Books edition 2006 by the Board of Regents of the University of Nebraska

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

First Bison Books printing: 1978

Bison Books edition published by arrangement with Albert L. Cole

"The Tragedy of the Sioux" was originally published in The

American Mercury 24, no. 95 (November 1931): 27378.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Standing Bear, Luther, 1868?1939.

Land of the spotted eagle / Luther Standing Bear; foreword by Richard N. Ellis; introduction to the new Bison Books edition by Joseph Marshall III.New ed.

p. cm.

ISBN-13: 978-0-8032-9360-1 (pbk.: alk. paper)

1. Teton IndiansSocial life and customs. 2. Teton IndiansGovernment relations. I. Title.

E99.T34S7 2006

978.004' 975244dc22 2006018872

E-book ISBN: 978-0-8032-9365-6

INTRODUCTION TO THE NEW BISON BOOKS EDITION

JOSEPH MARSHALL III

Luther Standing Bear was, in a sense, part of the Lakota Nation's greatest generation. He lived during the darkest and most traumatic cultural and geographic upheaval experienced by the Lakotas. His generation knew, firsthand, what they were losing when they gave up their free-roaming nomadic lifestyle for the static boundaries and physical limitations of the reservation. No other Lakota generation can claim that they have faced that particular challenge. They quickly realized that, though clashes with the military were mostly over, the Lakotas were in a different kind of war, one that would be fought on new and different battlefields. And the fact that there is still a Lakota culture is testament to their successes on those battlefields.

If there is one characteristic that identifies the Lakotas, it is adaptability. About two centuries before Standing Bear was born (in either 1863 or 1868), his ancestors were forced to leave the semisedentary woodlands lifestyle they had been living in the lake country of what is now Minnesota. They moved west and tried their luck on the northern plains, and they adapted to a new physical environment and embraced a new lifestyle. They became nomadic hunters, but they did not stop being Lakota.

Standing Bear's generation reacted to the demise of that nomadic hunting lifestyle in the only way they could: they adapted, but as their ancestors had done decades before, they retained the essence of being Lakota. Standing Bear's life was a microcosm of his generation's experience. He did not forget what he was or where he came from. Furthermore, and just as important, he gave a voice to his people.

Some of the tools that helped Standing Bear adapt to the new lifestyle he gained at Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania. Though he was initially resistant to the requirements and regimentation of Euro-American educationsuch as short hair and waiting in lineStanding Bear was regarded as one of Carlisle's success stories. But although Carlisle can claim to have educated him within the mandates of assimilation, they could not "kill the Indian" in Luther Standing Bear. If they had, his writings would have reflected a white viewpoint and not a Lakota stubbornly clinging to his individual and cultural identity.

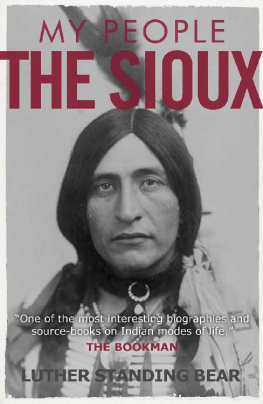

In 1928, fifty-two years after the Battle of the Little Bighorn, Standing Bear published his first book, My People the Sioux. By that time, many of the first reservation generation of Lakotas had passed on, but their trials and tribulations had not been forgotten. No matter how difficult or bitter those experiences might have been, they were much too important as life lessons to ignore. The stories were told to children and grandchildren, who were living their own experiences as the second and third reservation generations. Although Standing Bear wrote My People the Sioux (and other books) so that the Lakotas themselves would never forget an especially crucial time in their history, his primary reason for publishing his writings was the message they contained. He was telling white America that, for the most part, assimilation had failed as far as the Lakotas were concerned.

I can recall going to a spring carnival at St. Francis Indian School, on the Rosebud Reservation, in the mid-1950s. Several of my paternal cousins were going to school there. One of them greeted her parents, my father's brother and his wife, with the words "Long time, no see," in English. It was a popular phrase at the time, but it was somewhat of a shock to me because I knew my cousin could speak Lakota. That vignette is prominent in my memory, and over the years it has become, for me, the epitome of the axiom "When in Rome, do as the Romans do." My cousin was very much a Lakota in her values, which she lived by all her life.

Likewise, Luther Standing Bear was born a Lakota, and he died a Lakota. As a youngster he was known as Ota Kte, meaning "Kills Plenty" or "Plenty Kill." At Carlisle his name became Standing Bear, and he was taught to be a tinsmith, a vocation that he found no use for once he returned to the Rosebud Reservation. Later, however, he worked at a government school, a post office, and a mercantile. In 1902 he became part of Buffalo Bill's Wild West show, a job that took him to England for nearly a year. After moving to California in 1912, he found work as a screen actor.

Standing Bear is a role model for two reasons. First, he lived and moved in mainstream society as a Lakota. Second, he left behind a legacy as a writer. Judging from his writing, Standing Bear never had an identity problem; he always knew who he was. He was able to function and survive, and even thrive, in mainstream society because of that. He did not, it would appear, try to live his life as an imitation of white people to please them. Instead, he relied on the values that his Lakota family and community taught him. In that sense, he was an object lesson for anyone of any color or creed to be true to themselves. He also showed that what one appears to be on the outside is not necessarily the same as what drives one from the inside.

Standing Bear, or Ota Kte, would certainly have been remembered by his family and community even if he had not published any books. But because he did, his story is known to a wider audience. Just as important as his personal story is the cultural viewpoint from which he wrote. Early in the twentieth century, he expressed a reality that seems eerily applicable to the present:

The white man does not understand the Indian for the reason that he does not understand America. He is too far removed from its formative processes. The roots of the tree of his life have not yet grasped the rock and soil. The white man is still troubled with primitive fears; he still has in his consciousness the perils of this frontier continent, some of its fastnesses not yet having yielded to his questing footsteps and inquiring eyes. He shudders still with the memory of the loss of his forefathers upon its scorching deserts and forbidding mountain-tops. The man from Europe is still a foreigner and an alien. And he still hates the man who questioned his path across the continent.