THE STORY-TELLER

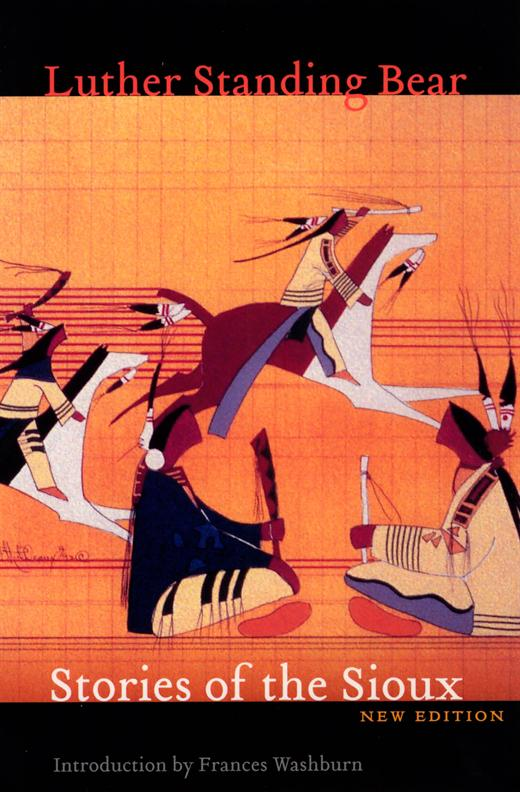

1934 by Luther Standing Bear

renewed 1961 by May M. Jones

Introduction 2006 by Frances Washburn

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

First Bison Books printing: 1988

Reprinted by arrangement with Dolores Miller Nyerges and Anita Miller Melbo

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Standing Bear, Luther, 1868?1939.

Stories of the Sioux / Luther Standing Bear; with illustrations by Herbert

Morton Stoops; introduction to the Bison Books edition by Frances Washburn.New ed.

p. cm.

ISBN-978-0-8032-9363-2 (pbk.: alk. paper)

1. Teton IndiansFolklore. 2. Dakota IndiansFolklore. 3. Indians of North AmericaGreat PlainsFolklore. I. Title.

E99.T34S73 2006

398.2089'97524dc22 2006016445

E-book ISBN: 978-0-8032-9368-7

INTRODUCTION

FRANCES WASHBURN

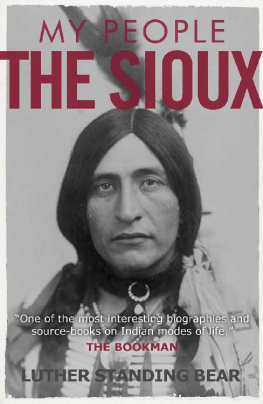

Everyone tells stories every day. Even the question "How was school today?" is an invitation from a parent to a child to tell a tale. Most of our stories are about mundane, everyday events and are meant to convey information or serve a social function by demonstrating interest in another person's life. But some stories, those told by master storytellers, also delight, entertain, and enlighten. Luther Standing Bear could tell such stories.

Born into the Brul, or Sicangu, Sioux tribe, Luther Standing Bear's arrival in life coincided with the Treaty of Ft. Laramie, which would eventually result in the confinement of Sioux people to reservations. He lived his childhood in that transitional time between the freedom of the Sicangu nomadic lifestyle and the curtailment of the Sicangu as wards of the federal government. There was no time for years of slow and gradually increasing contact, no time for Standing Bear and his people to absorb what was useful from the white, alien culture and to reject what was not. Change came over a period of only a few years with the pointing of guns and waving of Bibles. In 1879, at the age of eleven, Standing Bear found himself enrolled in Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania.

His experience was similar to that of other American Indian children, who were suddenly ripped from their homes and placed in a foreign environment that expected them to immediately begin speaking another language and living another culture. Standing Bear recalls dismay, anger, and sadness over a forced haircut but surprise and joy over new shoes. He came back to the Rosebud Reservation in South Dakota in 1884, vowing never to return to Carlisle.

Back home, Standing Bear was employed as an assistant in the local government school, and later he went on to supervise another government school on the Pine Ridge Reservation. He went to Europe with Buffalo Bill's Wild West show in 1902. Even though he traveled and made his living in this new world, Standing Bear maintained his traditional cultural ties. In 1905 he was chosen to replace his father as chief of his tiospaye, his clan or band. However, according to federal law, he was still a ward of the government with no control over his own property, so he traveled to Washington DC to petition the government for citizenship and the right to control his land allotment and trust money. That petition was granted, and along with citizenship came the right to travel on and off the reservation as he pleased, a right that Standing Bear exercised. For most of the rest of his life he lived and worked off-reservation, clerking in a store in Iowa, working on a ranch in Oklahoma, and, finally, performing as an extra in Hollywood movies such as The Santa Fe Trail (1930), Texas Pioneers (1932), and Fighting Pioneers (1935). Standing Bear was also an activist for American Indian causes. He participated in the League for Justice to the American Indian and lectured as an advocate for Indian rights. He died in Huntington, California, in 1939. Still, he is not remembered for his movie career or activism but rather for his storytelling.

Between 1928 and 1935 Standing Bear wrote and published essays, articles, and four books with the help of his niece Waste Win; Stories of the Sioux was first published in 1934. The people of the United States were in search of a national character, some way to root themselves to the land that they had claimed from the Indians, and many non-Indian citizens were fascinated with the culture and stories of American Indians. Standing Bear gave these to the world but with a different agenda. He intended to show that American Indians have values that transcend cultural difference, thereby demonstrating that Indians are, first and foremost, human beings.

Some of the stories in this collection describe human difficulties the problems of finding food, of sheltering from storms, of evading an unwanted marriageand the ways in which the Sioux solved those problems. Other stories honor wise and learned people within the tribe such as elders and medicine men, and still others, such as "Crow Butte," are explanations for place names.

The stories follow a form that contains the hallmarks of good storytelling. Each begins with a sentence designed to hook the reader's interest Then, in a paragraph or two, Standing Bear sets the scene and begins to unfold the story until a satisfactory conclusion is reached. The stories are spare, with every word carrying meaning, much like the stories from Sioux oral tradition, but they are understandable not just for Sioux people but for any culture, in any time and place.

We all tell stories, every day. Some of our stories are boring tales about what we did at work or school, but some are about family events, people we admire, or places we have been. These stories carry deep meanings and connect us to each other, to our individual spiritual beliefs, and to our place in the world. May you find something of value, some connection, in these stories of Luther Standing Bear.

PREFACE

T HE Sioux people have many stories which are told by the older ones in the tribe to the younger. Many main events and historical happenings of the tribe are told as stories and in this way the history of the people is recorded. These stories were not told, however, with the idea of forcing the children to learn, but for pleasure, and they were enjoyed by young and old alike. Some of these stories I have heard repeated many times. Others I have heard only once, but these I remember just as well. Perhaps it is because an Indian child is trained to use his ears carefully that his memory is so reliable.

These stories were not always told by the camp-fire during the long winter evenings, but at any time and at any place whenever and where-ever the teller and the audience were in the mood. Sometimes it was Grandmother who sat on the ground, perhaps with a small stick or drawing-pencil in her hand, drawing designs on the earth as she told a story that she had known ever since she was a child herself. The children would cluster around her, either lying or squatting on the ground listening.

Sometimes Grandfather or Great-Grandfather was the story-teller as he sat and smoked at noonday. Even when on the march, if all were enjoying an afternoon rest and someone felt in the humor, a story would be related and enjoyed. So story-telling was in order with the Sioux at any and all times.