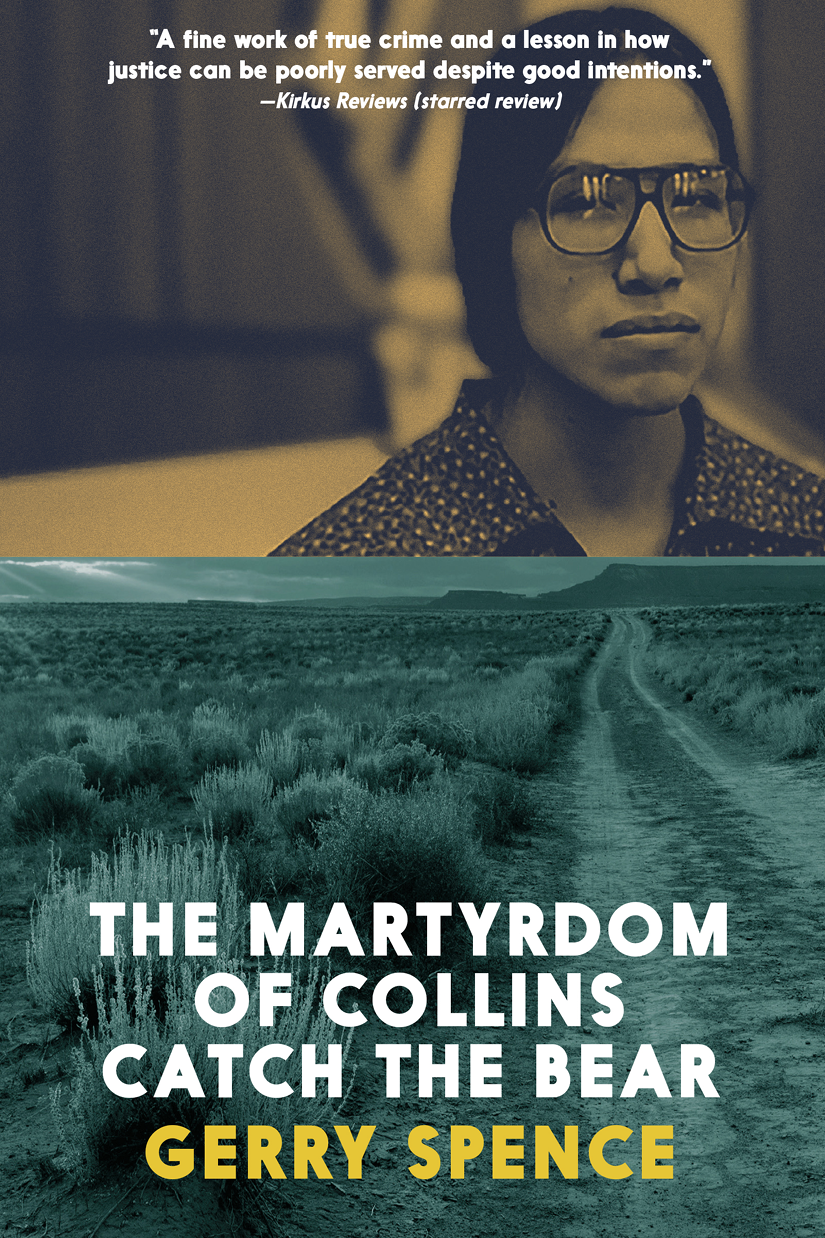

The Martyrdom of

Collins

Catch the Bear

GERRY SPENCE

Seven Stories Press

New York Oakland London

Copyright 2019 by Gerry Spence

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any

form or by any means, including mechanical, electronic,

photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the

prior written permission of the publisher

Seven Stories Press

140 Watts Street

New York, NY 10013

www.sevenstories.com

College professors and high school and middle school teachers may

order free examination copies of Seven Stories Press titles.

To order, visit www.sevenstories.com

or send a fax on school letterhead to (212) 226-1411.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Spence, Gerry, author.

Title: The martyrdom of Collins Catch the Bear / Gerry Spence.

Description: A Seven Stories Press first edition. | New York : Seven

Stories Press, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references. |

Identifiers: LCCN 2019056551 (print) | LCCN 2019056552 (ebook) | ISBN

9781609809669 (trade paperback) | ISBN 9781609809676 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Collins Catch the Bear--Trials, litigation, etc. | Lakota

Indians--Legal status, laws, etc.--South Dakota--History--20th century.

| Indians, Treatment of--North America--History--20th century. | Indians

of North America--Government relations--1934- | Trials (Murder)--South

Dakota--History--20th century. | Discrimination in criminal justice

administration--South Dakota--History--20th century.

Classification: LCC E99.T34 S64 2019 (print) | LCC E99.T34 (ebook) | DDC

978.004/9752440092 [B]--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019056551

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019056552

Book design by Jon Gilbert

I dedicate this book to Jim Leach, a lawyer who truly represents devotion. Jim counseled and fought for Collins Catch the Bear both in and out of court for most of Collinss adult life. He did so without pay or reward of fame and in the face of hopeless legal and personal obstacles. He never gave up. In his dedication to his client, he is a role model for all of us.

Prologue

Time has a way of amusing itself. But it soon grows bored with our heroic struggles, flips them into a pile of mortal foolishness, and forgets them. I thought this story was about an Indian who was assaulted by Times cruel, blinding decoy of hope, an Indian who fought back. History decrees our heroes. But history is often as foolish and as fickle as we.

Id written something like a hundred pages on an old electric typewritermy writers weapon in those daysabout my defense of Collins Catch the Bear, a Lakota Sioux whod been charged with the murder of a white man. Then Catch the Bear, without offering reason or explanation, which was his way, ordered that I stop writing. So, I tossed my work onto the top shelf of a closet, and the pages yellowed and curled in protest for nearly thirty years.

In the decades that hurtled by, I lost contact with Catch the Bear. I remembered him as a bright, articulate young man whod become dedicated to the cause of Indian rights, trying his lawyers patience with a host of problems, which I recount in the pages that follow. Then: silence. I supposed he was either in prison or rotting away on the reservation in South Dakota. Then, a short time ago, fate intervened, and I found myself freed to tell his story.

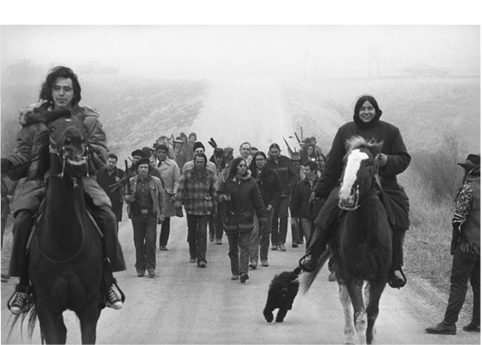

Americas attention to Indian rights, as capricious as it has been, was recently revived when representatives of 280 tribes from across the nation joined to peaceably protest the Dakota Access Pipelines invasion of sacred Indian lands in North Dakota. Indian demonstrations, both peaceful and deadly, were nothing new in the Dakotas. In 1973 the American Indian Movement (AIM), championed by Russell Means, the infamous Indian renegade, occupied the Indian village of Wounded Knee, in South Dakota, in a hostile seventy-one-day siege in which two Indians lost their lives and a federal officer was shot and paralyzed.

In 1982, the Lakota Sioux established the Yellow Thunder Camp, just outside Rapid City, South Dakota. This unauthorized encroachment on the National Forest was the progeny of the same Russell Means of the 1973 Wounded Knee occupation. Both whites and Indians had their say regarding the camp, and the killing continued: on July 21, Clarence Tollefson, a forty-nine-year-old white man from Rapid City was fatally shot at the camp. Such deadly confrontations seemed sealed in the genes of history.

Indian occupiers of Wounded Knee, March 13, 1972. This Associated Press photo appeared in the October 23, 2012, issue of Harpers Magazine .

According to the verbiage of Rodney Lefholz, then the states prosecutor, whod recently announced his candidacy for South Dakota attorney general, it was one Collins Catch the Bear who had shot and killed Tollefson, and justice demanded that he be forthwith charged, tried, convicted, and thereafter permanently eliminated from the population. In those days (and perhaps today in some quarters of the state), Indians were viewed with approximately the same affection as coyotes, rats, and other vermin.

Id been coaxed into the case by Jim Leach, of Rapid City, a kid whod been out of law school a few years but not long enough to shed his romantic notions, like Don Quixote in his chivalric search for justice. Leach was irrevocably wedded to the case. Why, I didnt know. But one thing Id learned (the hard way) was that embracing virtue often leads to unforeseen misadventures. Catch the Bears trial was imminent, and Leach said he needed my help defending him.

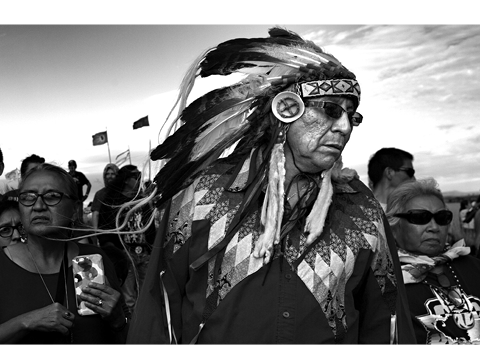

An elder of the Sacred Stone Camp appearing in support of the Standing Rock uprising of 2016. (Nima Taradji/Getty Images)

Before I take on any case, I try to discover who the client is. I want to know something about the seed and roots as well as the blossom. Collins Catch the Bear offered no remarkable history except multiple convictions for various crimes, and when I asked him about his life, he was often unresponsive or his answers vague. Moreover, he was unable to pay the first penny for his defense, covering not even the barest of expenses.

Ive long contended that lawyers ought not commit to a case unless theyve been able to discover, after a charitable search, something in the client they can care about at the heart level. Ive represented alleged killers and thieves and crooks of many stripes, and Ive found that if one cuts through the hard, often hostile survival armor of even the most depraved, one will often find a tortured soul: a child wounded by parents hopelessly lost to drugs and alcohol or, too often, stifled by utter povertybut under it all, a human being worth caring about.

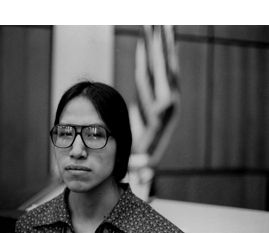

Collins Catch the Bear, March 1993

For Catch the Bears part, he often came off like a cipher in glasses. Perhaps, I thought, the tribal records would furnish more insights than the man seemed capable of providing. So, it was there that Leach and I started our archeological dig in search of Collins Catch the Bear. And, indeed, what we found was a young, lost Sioux in search of the same elusive person: himself.