Table of Contents

OTHER TITLES IN OTHER TITLES IN THE PENGUIN LIBRARY OF AMERICAN INDIAN HISTORY

The Cherokee Nation and the Trail of Tears

Theda Purdue and Michael D. Green

The Shawnees and the War for America

Colin G. Calloway

American Indians and the Law

N. Bruce Duthu

Iroquois Diplomacy on the Early American Frontier

Timothy J. Shannon

Cahokia: Ancient Americas Great City on the Mississippi

Timothy R. Pauketat

Ojibwe Women and the Survival of Indian Community

Brenda J. Child

GENERAL EDITOR: Colin G. Calloway

ADVISORY BOARD:

Brenda J. Child, Philip J. Deloria, Frederick E. Hoxie

For the next generation

INTRODUCTION

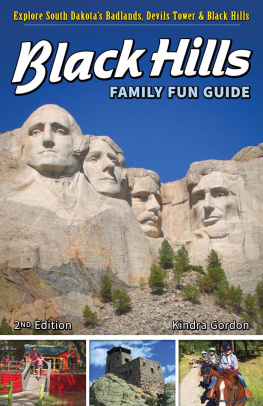

MOUNT RUSHMORE

EACH YEAR OVER three million tourists visit the Black Hills. Almost all stop at Mount Rushmore, where they gaze upward at four white faces carved into a granite wall. At the nearby museum, a display explains that the sculptor, Gutzon Borglum, chose the four American presidentsWashington, Jefferson, Lincoln, and Teddy Rooseveltto symbolize the principles of liberty and freedom on which the nation was founded.

The Mount Rushmore National Memorial, parking lot included, covers only two square miles of the six thousand that comprise the Black Hills. But the colossal scale of the four presidents (each sixty feet high) and their placement atop a huge wall of rock make Rushmore a powerful symbol of Americas ownershipnot only of the Black Hills but of a continental empire. The overwhelming permanence of Mount Rushmore conveys the impression that this empire might last forever.

Few visitors to the site likely give much thought to the previous owners of the Black Hills, a tribe of Native Americans called the Lakotas, who counted among their number some of the most well-known Indians in American history, including Crazy Horse and Sitting Bull. The displays at the memorial offer very little information about them. Visitors leave without learning about the treaties made between the Lakotas and the U.S. government in 1851 and 1868, which secured Lakota title to the Black Hills, or the 1877 act of congress through which the United States confiscated the Hills from the Lakotas. Recently, under the direction of Gerard Baker, Mount Rushmores first Native American superintendent, tour guides have begun including information about the United States taking of the Black Hills. But not all visitors enjoy hearing traditional stories of liberty and freedom complicated by lectures on injustice. Some complain, and the guides are asked to exercise restraint.

Lakota people do not like Mount Rushmore and have often seen the monument as an expression of the dominant cultures arrogance toward them. John Lame Deer, a Lakota medicine man, put it this way: whites, he said, could just as well have carved this mountain into a huge cavalry boot standing on a dead Indian. But despite the apparent permanence of Mount Rushmore, Lakotas do not see the United States ownership of the Black Hills as a settled fact. Indeed, most Lakotas hope to someday regain at least some of the land they have lost.

This idea probably strikes most Americans as far-fetched. President Franklin D. Roosevelt certainly would have thought so in 1936, speaking at Mount Rushmore, when he predicted that Americans ten thousand years from now would come to meditate on their memorial. Yet, perhaps surprisingly, the foundation for U.S. ownership of the Black Hills is not as secure as it once was. In 1980, the Supreme Court ruled that the governments seizure of the Black Hills violated the Fifth Amendments prohibition against the taking of property without just compensation. The Court affirmed a lower courts decision to award the Lakotas and other Sioux tribes $17 million for the value of the land in 1877 plus interest, for a total of $102 million. To the surprise of many outsiders, the Lakotas overwhelmingly rejected a monetary settlement. The Black Hills are not for sale, they said, and demanded that the land be returned. In 1985 New Jersey senator Bill Bradley, who had run a basketball clinic for Lakota youth a decade earlier, introduced legislation to recognize Lakota and other Sioux tribes title to most federal lands in the Black Hills. The remainder would stay in private hands. Although this was a fairly moderate proposal (only 18 percent of the total land in the Black Hills would have been affected), regional and local politicians scoffed at the legislation and suggested that Bradley mind the business of New Jersey. The Bradley bill eventually died.

Although it may seem unlikely that the Lakotas will regain Black Hills land, the future is more open than might be imagined. When the United States took the Black Hills in the 1870s, few would have predicted that the U.S. Supreme Court would condemn those actions a century later. Nor would most Americans have foreseen the survival of the Lakota people and the cultural and political revival they have experienced in recent years.

This book begins by explaining how the Lakotas lived in the Black Hills in the late 1700s and early 1800s and explores the cultural and religious meanings they gave to the land. It then tells the story of how Americans began to encroach on Lakota territory and how, despite efforts by Lakotas to defend the area, the United States wrested the Black Hills from them. Finally, the book narrates the Lakotas efforts to survive the loss of the Black Hills and to obtain redress for that loss.

The contest between the United States and the Lakotas for the Black Hills has given rise to different versions of the history told in this book. To justify their taking of the Black Hills in the 1870s, Americans argued that the Lakotas had never lived in the Black Hills at all. When in the early 1900s Lakotas began to seek monetary compensation for the taking of the Hills, many Americans vigorously defended the righteousness of their governments actions in the 1870s. In recent decades, as Lakotas began to demand that the land be returned, some contended that Lakotas had invented the idea of the Black Hills as sacred ground to justify their cause. Against these views, Lakotas insist that they have lived in the Black Hills for centuries, if not millennia, that the Black Hills have always been sacred ground, and that the United States theft of their land was an injustice that must be set right.

Because historical arguments have played (and will likely continue to play) a crucial role in the struggle for the Black Hills, any history of that struggle is of more than academic interest. Although no single version of that history dictates what ought to be done, which version is accepted will undoubtedly have an impact on ongoing debates about the future of the land. In writing this history of the Lakotas and the Black Hills, I have tried to be as accurate as possible, while at the same time realizing that it is impossible to be certain about all of the issues. Few readers, I imagine, will agree with all of my interpretations, but I hope that this book will be useful to those seeking a better understanding of the contested history of the Black Hills and the Lakota people who continue to hope for the return of their land.