Surviving Genocide

Surviving Genocide

NATIVE NATIONS AND THE UNITED STATES FROM THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION TO BLEEDING KANSAS

Jeffrey Ostler

Yale UNIVERSITY PRESS

New Haven & London

Published with assistance from the Annie Burr Lewis Fund.

Published with assistance from the Oregon Humanities Center and the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Oregon.

Copyright 2019 by Jeffrey Ostler.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail sales.press@yale.edu (U.S. office) or sales@yaleup.co.uk (U.K. office).

Set in Adobe Garamond type by Newgen North America.

Printed in the United States of America.

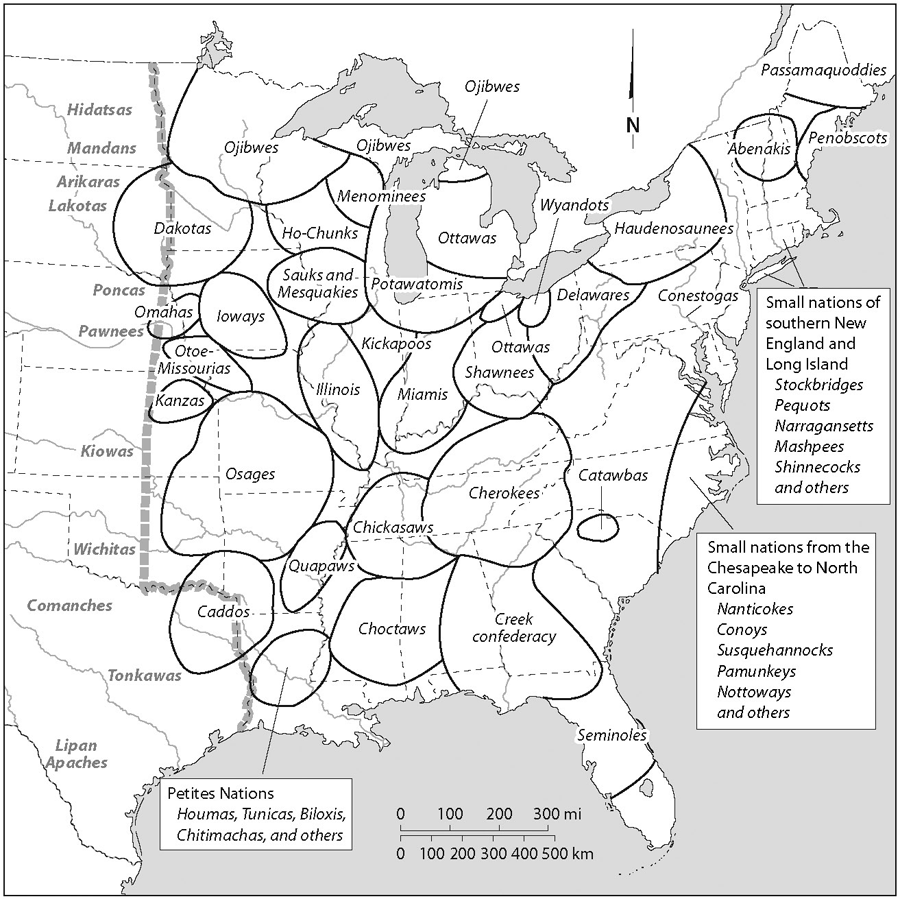

The maps are by Bill Nelson.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018958482

ISBN 978-0-300-21812-1 (hardcover : alk. paper)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To University of Oregon graduate students, past and present

Contents

Note on Terminology

Native America has always included hundreds of distinct communities, often tied to other communities through kinship relations and common cultural traditions and with changing identities over time. In this book, I often refer to particular sets of communities as nations and treat them as relatively discrete and stable entities. My reason for doing so is twofold: first, to recognize the sovereignty of Native peoples, and second, to facilitate narration. My decisions, however, involve some simplifications. The Creeks, for example, are a multilingual confederacy in which local identities were often paramount. Similarly, Ojibwes, Ottawas, and Potawatomis, which I generally treat as three separate nations, formed the Three Fires, which in turn was part of a larger group known as the Anishinaabe, which included Nippisings, Mississaugas, Algonkins, and others. With a few exceptions, I have used the most current name for each Native nation and have noted alternative or earlier names in parentheses.

Introduction

AN ICY RIVER AND A RAGING SEA

In December 1831, while on the east bank of the Mississippi River at Memphis, Alexis de Tocqueville witnessed a band of Choctaws being forced west from their homelands by the United States government. In a little-known section of his otherwise famous Democracy in America, Tocqueville recalled that the cold was exceptionally severe; the snow was hard on the ground, and huge masses of ice drifted on the river. The Choctaws brought their families with them; there were among them the wounded, the sick, newborn babies, and the old men on the point of death. As the Choctaws embarked on a steamboat to cross the river, neither sob nor complaint rose from that silent assembly. Soon, however, Tocqueville heard a terrible howl. Left on the riverbank, the Choctaws dogs had realized that they were being left behind forever. Still howling, the dogs plunged into the icy waters of the Mississippi to swim after their masters. The implicit fate of their animals forecast a similarly grim future for the Choctaws. Tocqueville predicted that they would soon cease to exist.

In using Choctaw removal as an example of the destruction of Indians under American democracy, Tocqueville posed one of his characteristic paradoxes. The Spaniards, he observed, committed unparalleled atrocities which brand them with indelible shame, but even so they did not succeed in exterminating the Indian race and were even forced to give Indians their rights.

Tocquevilles contrast between an American bloodlessness that was ultimately more destructive than Spanish cruelty exposed the hypocrisy of Anglo Protestantism by standing the Black Legend of Spanish atrocities on its head. Nonetheless, Tocqueville seriously understated Americans violence toward Indigenous people. Tocqueville was also mistaken in predicting that the Choctaws would disappear. Despite unfathomable suffering and terrible loss of life, the Choctaw Nation survived removal. (In fact, Tocquevilles account of the dying dogs as an omen of Choctaw disappearance was inaccuratein a letter to his mother written at the time, Tocqueville related that the dogs actually boarded the steamship.) Despite these flaws, however, Tocqueville put his finger on the undeniable fact that U.S. expansion unleashed destructive forces on American Indian nations. He also identified what may be a particular genius of the American people: their ability to inflict catastrophic destruction all the while claiming to be benevolent.

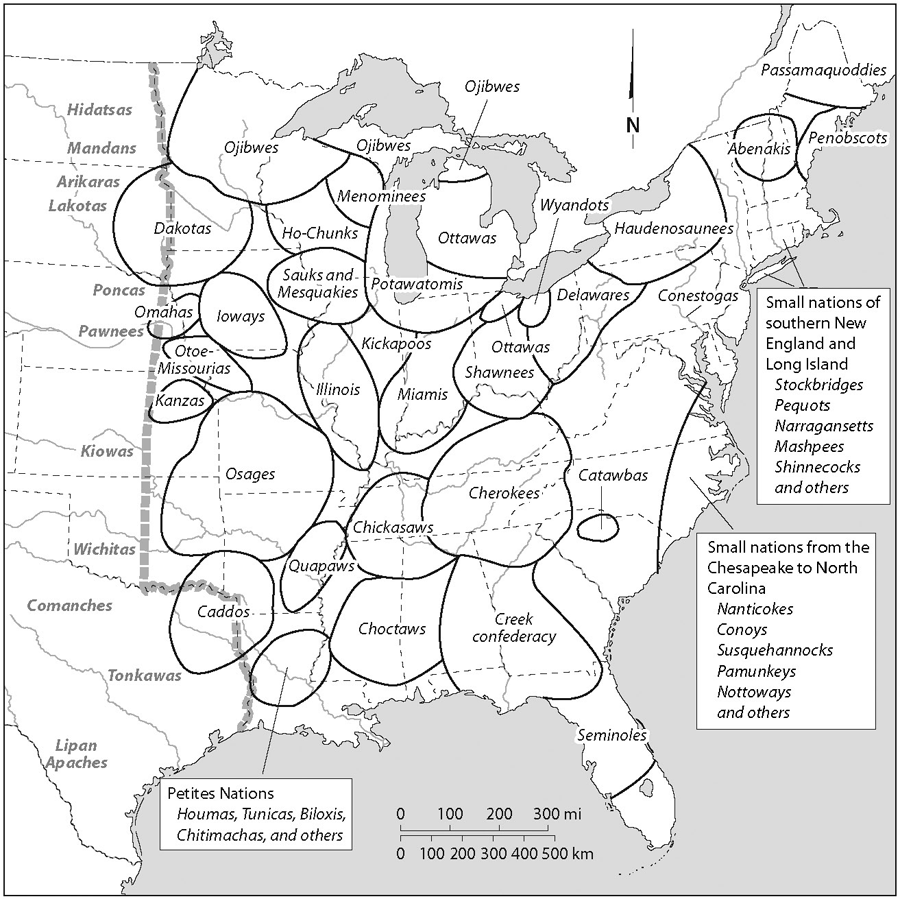

Since Tocqueville wrote about the United States destruction of American Indians, thousands of books have been produced about Native people, U.S. Indian policy, and U.S. warfare against Native communities. Despite this, we lack a general overview of the impact of U.S. expansion on American Indian nations. This book is the first of two volumes intended to provide a comprehensive overview. This volume covers roughly the eastern half of the United States from the 1750s to 1860. As shown in events, and phases of U.S. policy. I have also drawn on an array of published primary sources produced by missionaries, traders, travelers, correspondents, ethnographers, and government officials. Many of these sources contain the voices of Native people, and I have tried to bring these voices into the narrative. I have also incorporated the writings of Native people themselves.

Fig. 1. Geography of the book, showing territories of Native nations around 1760 (dashed lines indicate modern state boundaries)

What exactly was the impact of U.S. expansion on American Indian nations? How destructive was it? How did Indians respond to destructive forces? To what extent and how did they survive? To begin to answer these questionsthe central questions of this bookwe need to first recognize that one of the basic purposes of the United States was to take the lands of Native people and to make them available to speculators and settlers, including

The United States imagined several ways that Native people might be dispossessed. One possibility American leaders envisioned was that Indians would conveniently disappear as a result of seemingly natural and supposedly inevitable historical trends. This self-serving fantasy, however, did not happen. American leaders also talked a great deal about another possibility, that the United States might civilize Indians and assimilate them into American society. Historians have generally accepted American leaders professions of a desire to civilize Indians at face value. In my view, however, U.S. officials were never seriously committed to a policy of civilization. As early as Thomas Jeffersons presidency (18011809), U.S. actions made it clear that despite talk of civilization and assimilation, the United States would ultimately pursue a third option for the elimination of Indians east of the Mississippi River: they would be moved west of the Mississippi. For practical reasons, it was not possible to implement a full-scale policy of removal until 1830 with the passage of the Indian Removal Act. In the meantime, the United States took a piecemeal approach to eliminating Indian lands and opening them to settlement by demanding that Native nations agree to treaties that ceded a portion of their lands. The preference of U.S. officials was for Native nations to willingly accept demands for their lands, but many Native leaders refused to agree to land cession treaties. These leaders regarded treaties that other leaders signed (almost always under coercive pressure) as illegitimate and often turned to militant resistance to defend their lands. When this happened, U.S. officials pursued another policy option: genocidal warfare. For several reasons, including cost, lack of capacity, and the necessity to appear to be acting according to Tocquevilles laws of humanity, the United States did not make outright genocide its first option for elimination. But, as this book will show, U.S. officials developed a policy that wars of extermination against resisting Indians were not only necessary but ethical and legal.

Next page