Table of Contents

For Carole and Marty

Acclaim for Alan Taylors

The Divided Ground

A comprehensive account of [the Indians] from the Revolutionary period to the first years of the nineteenth century in what is now western New York, Pennsylvania and Ontario. The Nation

Powerful and poignant, The Divided Ground treats Indians as vital players and not just as victimized pawns in the post-Revolutionary struggles to establish borders and grab property. Stephen Aron, author of American Confluence

Readable and erudite.... Taylor captures the essence of this transient frontier. Here we have native Indians seeking to preserve their own autonomy, while accepting the incoming whites as a reality. The Decatur Daily

The story is a poignant one.... Taylor is a prodigious researcher and he has investigated, it seems, nearly all of the documentary record as it relates to the late-eighteenth-century Iroquois. The New York Review of Books

Illuminating and even-handed.... A grand tale of mutual need and mutual suspicion. Kirkus Reviews

Alan Taylors magisterial The Divided Ground offers exciting new perspectives on the history and legacies of the American Revolution.... A magnificent achievement. Peter S. Onuf, author of Jeffersons Empire

A rich, sprawling history... told by a master of the trade. Publishers Weekly

INTRODUCTION

Wheelocks School

JOSEPH BRANT first met Samuel Kirkland in the summer of 1761. Although raised in radically different cultures, they were both students at a colonial boarding school run by Rev. Eleazar Wheelock in Lebanon, Connecticut. Brant was an eighteen-year-old Mohawk Indian from Canajoharie, a village in the Mohawk Valley, on the northwestern frontier of New York. Originally named Thayendenegea, he became Joseph Brant after his Christian baptisma double identity common for Mohawks who lived among growing numbers of settlers. A year older, Kirkland felt far more at home at the school because he came from the nearby town of Norwich and was the son of a minister.1

Wheelocks controversial school trained colonial and Indian boys to become schoolteachers and missionaries for posting in Indian country. Pious and immensely ambitious, Wheelock pursued a Grand Design: the conversion of all Indians to Protestant Christianity and to the economic culture of colonial America. The Mohawks were critical to the plan, for they were widely considered the most important and influential natives on the frontier of British colonial America. Success with the Mohawks would, Wheelock anticipated, unlock the minds and souls of all the other Indians deep within the continent. But swaying the Mohawks hinged upon converting and training Brant, Wheelocks first student from that people. In 1761, Wheelock paired Brant with Kirkland for training as an elite missionary team. Brant taught Mohawk to Kirkland, who helped Brant to master English.2

SIX NATIONS

Brant enjoyed the patronage of Sir William Johnson, the most famous and powerful colonist on the American frontier of the British Empire. An Irish immigrant of immense charm, cunning, and ambition, Johnson had settled in the Mohawk Valley during the late 1730s. He became wealthy and influential by cultivating the support of Mohawk chiefs and the patronage of royal governors. In 1756, that combination secured his appointment as the kings superintendent for Indian affairs in the northern colonies. Given the importance of the Indians to frontier peace, Johnson held the most difficult and the most powerful position in British America.3

By assisting the British conquest of Canada, Johnson enhanced the security and the value of his personal domain of 50,000 acres located on the north side of the Mohawk River. To clear and cultivate that land, Johnson recruited settlers who paid rent as tenants. To honor his royal patron, Johnson named his estate Kingsborough. To flatter himself, Johnson founded a new town called Johnstown, and he built a grand mansion known as Johnson Hall. Befriending the Mohawks had enriched Sir William.4

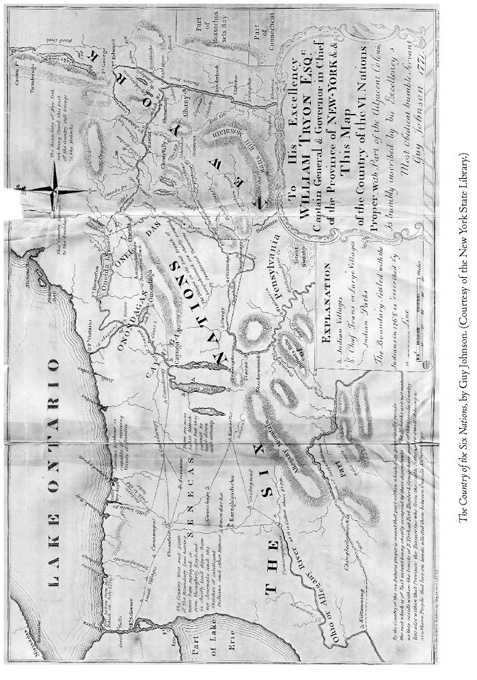

Although only about 400 people, the Mohawks derived extra clout from belonging to a broader Iroquois confederacy known as the Six Nations, which also included (from east to west) Oneidas, Tuscaroras, Onondagas, Cayugas, and Senecas. Especially numerous, the Senecas composed about half of the Iroquois total of 10,000 people. Culturally similar, the Six Nations spoke kindred languages of the Iroquoian family, with the greatest affinities between the Mohawk and Oneida tongues. Their aggregate homelandIroquoiaextended westward from the Hudson Valley to Lake Erie, and from Lake Ontario and the Adirondack Mountains on the north, into Pennsylvania to the south.5

The Mohawks occupied two villagesCanajoharie and Tiononderoge (Fort Hunter)in the Mohawk Valley, while the Oneidas and Tuscaroras shared the country around Oneida Lake and in the upper Susquehanna Valley. Farther west, the Cayugas and Onondagas held the confederations heartland around the Finger Lakes. At the western edge of Iroquoia, the Senecas dwelled beside Seneca and Canandaigua lakes and in the valleys of the Genesee and Allegheny rivers.

The Iroquois nations occupied different points on a spectrum of colonial influence, with the eastern villages facing the greatest pressure from settlers. By 1761, the Mohawks were a shrinking minority surrounded by thriving settlements. The Oneidas and Tuscaroras were not yet enveloped, but they lived on the western margins of colonial settlement. To the west, the Cayugas, Onondagas, and Senecas enjoyed greater independence and security because they retained large homelands beyond the colonistsfor the time being.6

The colonists coveted the Iroquois as allies because they occupied the most strategic position in northeastern North America: along the waterways through the Appalachian Mountains between New York and French Canada, to the north, and between New York and the Great Lakes, to the west. Given the impossibility of moving armies with cannon through dense woods and across mountains, British officers needed to control the waterwaysat least to defend New York and at best to attack Canada. As raiding enemies, the Iroquois might devastate the colonial frontier, but as allies they could provide an invaluable screen against attacks by more distant Indians allied with the French. The Iroquois location next to our portages & Frontier Settlements, Sir William Johnson explained, qualifies them for acting the part of our best friends, or most dangerous enemies. 7

The Iroquois compounded the power of their position by their formidable reputation as warriors and scouts, as the masters of a forest warfare of sudden raids and deadly ambushes. Indian warriors terrified both by their silent mobility in advanceand by their sudden sound and fury in attack. Their distinctive, piercing screams chilled all but the most hardened foes. An Iroquois warrior also cultivated a formidable appearance by stripping naked except for a loincloth and moccasins; by shaving his head but for a central ridge of hair known as a scalp lock; by tattooing his body with pins and gunpowder to symbolize his kills and captures in combat; by painting his face in some personalized medley of red, black, and blue; and by mutilating his ear-lobes, weighted with ornaments to drape onto both shoulders. 8

Next page