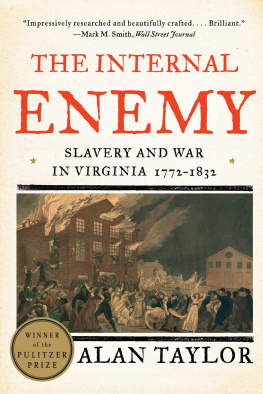

Alan Taylor - The Internal Enemy: Slavery and War in Virginia, 1772-1832

Here you can read online Alan Taylor - The Internal Enemy: Slavery and War in Virginia, 1772-1832 full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2013, publisher: Norton, W. W. & Company, Inc., genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Internal Enemy: Slavery and War in Virginia, 1772-1832

- Author:

- Publisher:Norton, W. W. & Company, Inc.

- Genre:

- Year:2013

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Internal Enemy: Slavery and War in Virginia, 1772-1832: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Internal Enemy: Slavery and War in Virginia, 1772-1832" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Internal Enemy: Slavery and War in Virginia, 1772-1832 — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Internal Enemy: Slavery and War in Virginia, 1772-1832" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

ALSO BY ALAN TAYLOR

The Civil War of 1812:

American Citizens, British Subjects, Irish Rebels, & Indian Allies

The Divided Ground:

Indians, Settlers, and the Northern Borderland of the American Revolution

Writing Early American History

American Colonies:

The Settling of North America

William Coopers Town:

Power and Persuasion on the Frontier of the Early American Republic

Liberty Men and Great Proprietors:

The Revolutionary Settlement on the Maine Frontier, 1760-1820

For Alessa, Chris and Gabriel

Andin memory ofEmory G. Evans

CONTENTS

I do not wish, sir, to leave my master, but I will follow my wife and children to death.

DICK CARTER, APRIL 22, 1814

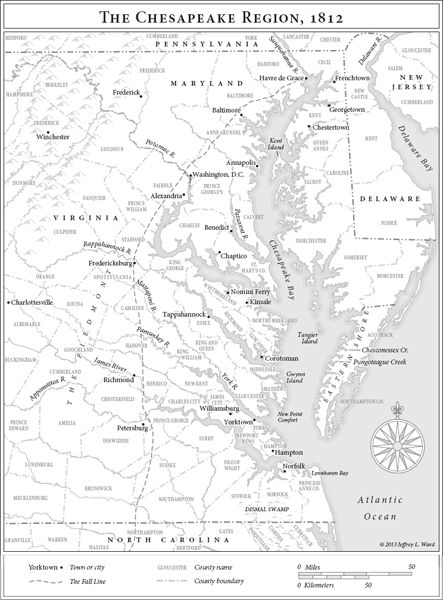

Maps

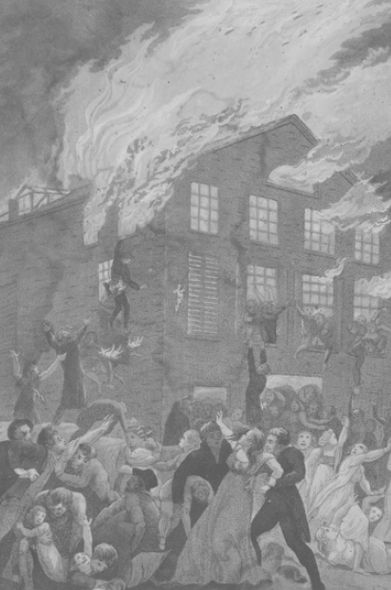

Illustrations

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Unfortunately, we have two enemies to contend withthe one open & declared; the other nurtured in our very Bosoms!

Sly, secret & insidious: in our families, at our Elbows, listening with eager attention; and sedulously marking all that is going forward.

ROBERT GREENHOW, MAYOR OF RICHMOND, 18131

O ne night in October 1814, on the Virginia shore of the Potomac River, several young enslaved men stole a canoe and paddled across the river to Laidloes Ferry on the Maryland shore. Abandoning the canoe, they took the larger ferry boat, for they needed a craft big enough to carry away seventeen people. Returning to the Virginia shore, the men retrieved wives and children for a dash down the river to seek a British warship as their portal to freedom. In the morning, their masters discovered that the slaves were gone and, in the words of one witness, had taken many articles out of Mr. [Abraham] Hooes dwelling house in the course of the Night [and] all their own articles & effects out of their houses. Armed white men rowed a swift boat in pursuit down the river, but in vain, for the slaves had reached the warship.2

During the War of 1812, Royal Navy warships pushed into Chesapeake Bay and up the Potomac River to punish the United States for declaring war against the British Empire. The Royal Navy attacked the region as the home of the national capital, a heartland of economic resources, and, in the case of Virginia, a hotbed of pro-war sentiment. The naval raids created an opportunity for the enslaved to escape and become free. Hundreds enlisted in the British service as sailors and marines or served as laundresses and nurses.

The ferry-boat escape aptly represented slave flight to the British during the War of 1812. First, this escape exposed the links of kin and friendship that constructed African American communities across several farms in a broad neighborhood, for the seventeen runaways had belonged to four different men, led by Abraham B. Hooe, who lost eleven slaves that night. Second, the runaways were especially valuable slaves: able, young, and skilled as artisans or house servants. Assessed at nearly $8,000 in total, the seventeen included two blacksmiths, two carpenters, a weaver, and two cooks. Third, most of these fugitives were young men, aged eighteen to thirty-five, with only one over that age, but the group also included two young women and three children. Indeed, the war enabled many enslaved families in the Tidewater to flee together. Fourth, this escape demonstrated careful planning and coordination as young men assembled kin and property and procured a craft big enough for all. They were far savvier than their masters had imagined.3

Five and a half years later, the leader of the escape wrote a letter to his former master, Hooe. In October 1814, Bartlet Shanklyn had been a prized blacksmith, thirty-five years old and worth $800: the most valuable of the runaways. In May 1820 he was thriving as a free man in Preston, a black township near Halifax in Nova Scotia, and he wanted Hooe to know it:

Sir, I take this opportunity of writing these lines to inform you how I am situated hear. I have [a] Shop & Set of Tools of my own and am doing very well when I was with you [you] treated me very ill and for that reason i take the liberty of informing you that i am doing as well as you if not beter. When i was with you I worked very hard and you neither g[ave] me money nor any satisfaction but sin[ce] I have been hear I am able to make Gold and Silver as well as you. The night that Cokely Stoped me he was very Strong but I showed him that subtilty Was far preferable to strength and brought away others with me who thank God are all doing well. So I Remain, Bartlet Shanklyn

P.S. My love to all my friends. I hope they are doing well

As a free man, Shanklyn could, at last, make his own money. Virginia slaves were third- and fourth-generation Americans who knew the social value of a dollar as the measure of a mans merit. Indeed, the runaway had become a better man than the master who had treated him so very ill by keeping him down, for Shanklyns prosperity did not rely on enslaving others. Cokely was apparently a powerful man, perhaps an overseer, who tried to restrain Shanklyn on the eve of the escape, but the clever blacksmith had outwitted the foe to lead family and friends to freedom. Slavery had taught the value and the ways of subtilty to the enslaved, who had to mask their knowledge and resistance. Rather than destroy the rebuking letter, Hooe showed more greed than pride by submitting it as evidence in a bid for postwar compensation from the federal government. Hooes choice preserved Shanklyns words for future readers.4

About 3,400 slaves fled from Maryland and Virginia to British ships during the War of 1812. After the War of 1812, most of the refugees resettled in Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Trinidad, while a few scattered throughout the global British Empire. In their new communities, the refugees confronted discrimination, but they achieved far more autonomy and material success than they had known as slaves in the Chesapeake. In contrast to the earlier runaways of the revolution, the War of 1812 fugitives have received little attention from historians. Consequently, distortions persist, including the popular canard that the British resold the runaways into a worse slavery in the West Indies.5

Fortunately, the experiences of the runaways are richly documented, especially in the postwar files submitted by their former masters seeking compensation. The files include depositions describing dramatic escapes, affidavits reconstituting slave families, and even a few postwar letters from runaways to relatives and former masters. By drawing on those largely untapped sources, this book examines the causes, course, and consequences of the flight by slaves to join and help the British. While focusing on the war years of 18121815, The Internal Enemy situates that conflict in a longer history of slavery and freedom in Virginia, the early republics largest and most powerful state. Rather than offer a conventional military history of the Chesapeake campaigns, which other historians have already done, this book taps the unusually rich documents generated by war to reveal the social complexities of slavery in Virginia from the American Revolution through Nat Turners revolt in 1831.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Internal Enemy: Slavery and War in Virginia, 1772-1832»

Look at similar books to The Internal Enemy: Slavery and War in Virginia, 1772-1832. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Internal Enemy: Slavery and War in Virginia, 1772-1832 and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.