The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

CONTENTS

For Bobs, Liza, and Tom

PREFACE

The American Revolution, the extraordinary act that gave birth to a nation and changed the history of the world, was not something that was plotted long in advance. No plans for revolt or independence from Great Britain occupied the minds of colonial Americans prior to 1760, and even then, only a handful of malcontents may have imagined a separation from what was thought of as the mother country.

The distant stirrings of what became a revolution dated back to the early 1700s, to the days when Robert Walpole was the first real prime minister in British history. Walpoles view of the American colonies was that they should be let alone, largely unhindered by restrictions from the home government, let alone to do what colonies were expected to dowhich was to produce enough food to sustain themselves, to export raw materials needed in Great Britain, such as timber, tobacco, rice, and indigo, and to buy from England all the manufactured goods they required.

Walpoles policy, which became known as salutary neglect, not only gave the colonies free rein, but unintentionally pushed them in the direction of self-government and an independent attitude. Over the years, without even realizing it, they became capable of managing their own affairs, and the habit was seductive, productive, and satisfying.

The struggle between England and France for possession of North America began in 1754 in what is now western Pennsylvania with an exchange of gunfire between some 150 Virginians led by the twenty-one-year-old George Washington and a party of French and their Indian allies. Known in America as the French and Indian War (the fourth conflict of that name in the eighteenth century) and in Europe as the Seven Years War, it became the first world war fought on three continents.

When the conflict at last ended in 1760 a sea change took place in America. That year the lucrative business of supplying the British army ceased, causing extreme financial pain for Americans in general and New Yorks merchants in particular. At the same time, old King George II died and was succeeded by his twenty-year-old, untried, inexperienced grandson, who was crowned George III. Stubbornly determined to reduce the huge national debt caused by the war, and equally resolved to make the colonists pay their share of it, George III and his ministers set in motion the chain of events that climaxed in the war of the Revolution.

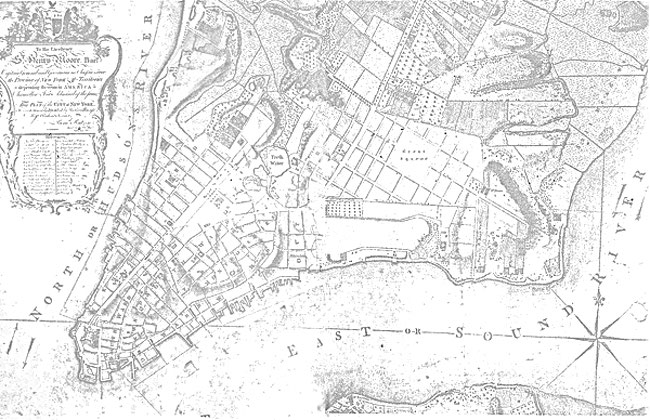

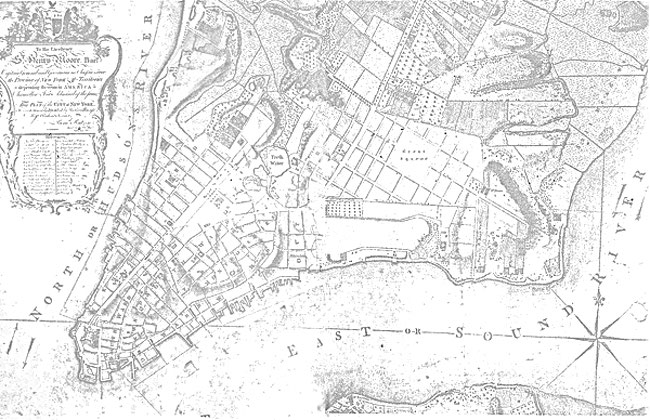

New York was said to be the kings favorite of the thirteen colonies. It was centrally located between the fractious New Englanders and the middle and southern colonies. At a time when the easiest way to travel or to ship goods was by water, New York not only had one of the worlds great ports, it had in the Hudson River unparalleled access to the vast interior of North America. That made it, for the British, a hugely important factor in the empires economy.

During the early 1760s, when the colonists were increasingly frustrated and angered by Britains efforts to impose taxes on them where none had existed before, officials in London had the impression that New York had a larger loyal contingent than other colonies. For as long as anyone knew, men and women had been subjects of a king and paid him homage. For a good many years after George III ascended the throne, most Americans instinctively revered him as a good king, a man to whom they owed loyalty and devotion. But in a few years time things began to come apart, and that is the story of this book. It is, however, more than an account of the widening rift and the eventual rupture in the relationship between England and America. It is also about loyalties.

It took a long timefifteen years or morefor people to realize that they had to take sides. Which is not to say that everyone did. As John Adams recalled it, about one-third of the colonists remained loyal to the king, another one-third did not, and the remaining one-third were uncommitted, or neutral.

It is with those first two-thirds that this book is principally concerned, for in the event of an upheaval as profound as a revolution, the people who take sides are those who care deeply enough to risk their lives, their families, and their fortunes in support of a cause in which they believe. More than two centuries later, if we think about this at all we are inclined to think that our side won the Revolution. After all, we are their inheritors, their beneficiaries, and what we have today we owe to those heroic men and women who struggled against all odds to obtain the freedom that meant more to them than anything else in life.

But because our side won, we forget that there was another side just as committed, just as dedicated, equally certain of the rectitude of their beliefs. Yet most of us have never given them a second thought because they were the losers. In the French Revolution the losers lost their heads, along with everything else. In America the treatment of Tories may have been less barbaric, but punishments were cruel, and it is worth asking whether a quick death may not have been preferable for some of those individuals who were forced to endure what amounted to a slow death in poverty and exile, deprived of what they regarded as their country, the land they loved, perhaps having lost a brother, a son, or a close friend who had chosen the other side.

We tend to think of the loyalists as rich, arrogant, unbending, concerned only for the privileges to which the wealthy are accustomed. And indeed many of them were arrogant upper-class snobs. But many were nothing of the kindmerely good people who chose to remain loyal to their king, as we todaymost of usare loyal to our government, despite its many faults, despite its flaws and blemishes, its frequent wrongheadedness and shortsightedness.

This is an account of how the Revolution came to one American town, New York, and the role people played as the forces of resistance and reform gradually gathered momentum and turned into something far more devastating and destructiverevolution. All this against a background described by Patricia Bonomi: New York was almost continuously riven by one form or another of internal strife.

Insofar as possible I have tried to tell the colonists story as they saw it and wrote it, drawing on their letters, journals, and diaries, as well as on contemporary newspapers. Often this has led to quoting a phrase that is unfamiliar to us, but that suggests their turn of speech. And of course the way certain individuals spelled a word can indicate how they pronounced ita lively example is Marinus Willetts use of Congersenal for Congressional. In the mid-eighteenth century, jail was usually spelled gaol or goal. Lenity was lenience; jealousy meant suspicion, not envy; where they said least, as used in the phrase least it might divide us, we say lest; writing to a friend in England, a New Yorker would say on your side the water, not on your side of the water; describing where an open-air meeting was held, he might say it took place without doors, rather than out of doors.

Next page