Preface

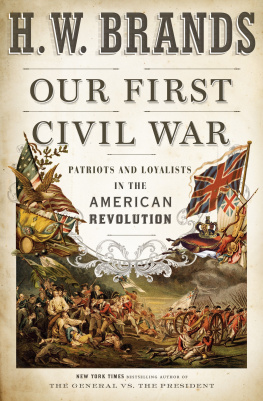

LITTLE LESS THAN SAVAGE FURY

O ne of my earliest childhood memories takes me to Putnam Park, near Danbury, Connecticut. The park was named after Maj. Gen. Israel Putnam. I still remember the cannons and a cave. My mother told me that soldiers who fought in the Revolutionary War spent a cold, hungry winter there. That was my first lesson about the war.

My mother did not tell me about Gallows Hill. On a February day in 1779, while his Continental Army division was in winter camp, General Putnam, infuriated by the number of spies and army deserters who had been brought before him, decided to execute one of each make a double job of it, he said. The spy was Edward Jones of Ridgefield, who, as an American supporter of the British was a Loyalist, or Tory. The deserter was seventeen-year-old John Smith, who was accused of planning to join the British Army as a Tory convert. Smith and Jones, ordinary men of ordinary names.

Smith spent a few minutes with a chaplain. Then, within a hollow square formed by the soldiers he wished to fight, Smiths death warrant was read. He was taken off and killed by a firing squad, a few yards from a gallows that soldiers had built on the highest hill in theencampment. Jones was brought to it, and his death warrant was read. A noose around his neck was attached to the beam of the gallows. He climbed a ladder leaning on the beam, looked around at people he seemed to recognize, and swore to God that he was innocent. When he refused to step off the ladder, as one account puts it, he had to be hurried into eternity, presumably by a soldier, although one report says young boys pushed the ladder.

As that day on Gallows Hill so lethally demonstrated, some Americans wanted to kill other Americans in the Revolutionary War. What had begun as political conflict between politicians called Whigs and their opponents, called Tories, had evolved into a brutal war. Our histories prefer to call the conflict the Revolutionary War, but many people who lived through it called it civil war. Americans who called themselves Patriots taunted, then tarred and feathered, and, finally, when war came, killed American Tories. Americans who called themselves Tories gave themselves a proud new name: Loyalists, a label that had not been needed when all Americans were subjects of the king.

When Brig. Gen. Nathanael Greene took command of the Continental Army of the South in 1781, he wrote to Col. Alexander Hamilton: The division among the people is much greater than I imagined and the Whigs and Tories persecute each other, with little less than savage fury. There is nothing but murders and devastation in every quarter.

There was also collaboration. When we remember the heroic suffering of George Washingtons army at Valley Forge, we forget that only twenty miles away the British soldiers occupying Philadelphia were well housed and well fed because Tories and Tory sympathizers were sustaining them. I am amazed, wrote Washington to a staff officer, at the report you make of the quantity of provisions that goes daily into Philadelphia from the County of Bucks.

Like most Americans, as a schoolboy and as an adult I had heard about the Tories, but I had not paid them much attention, believing that, as a small minority, they had not played a major role in the war. As a native of Connecticut, I had always thought of my state as a place where all the people fought the British. But soon after I started working on this book, I came across a reference to a Connecticut man named Stephen Jarvis, who had become a Tory soldier and killed other Americans. He was one of many Connecticut people who chose the kings side, and his story is far from unusual. Such Connecticut towns as Stamford, Norwalk, Fairfield, Stratford, and Newtown had such large Loyalist populations that Patriots called them Tory Towns.

Stephen Maples Jarvis, born in Danbury in 1756, was working on the family farm in April 1775 when he heard the news that British Redcoats and Rebels had clashed at Lexington and Concord in Massachusetts. My father was one of those persons called Torries, Stephen later wrote, quickly veering in his journal to his own clash with his father. Stephen, going on nineteen, was courting a young woman, Amelia Glover, who was disapproved of by my father and I was under the necessity of visiting the Lady only by stealth.

To defy his fatherand perhaps to impress his girlfriendStephen declared that he would join the Rebels Connecticut militia. When Stephen told his father this, the elder Jarvis took me by the arm and thrust me out of the door.

At that moment in those turbulent times, when general discontent over British rule had flared into rebellion, the divided Jarvis family mirrored the splitting of families and friends throughout the colonies. Amelia Glovers sister was married to a Rebel. Royal colonial militias overnight became Rebel militias. The militia that Stephen joined, originally formed to serve the king, was commanded by his mothers brother, a Rebel.

In Stamford, thirty miles southwest of Danbury, Stephens uncle on his fathers side, Samuel Jarvis, was the town clerk. Soon after the Battles of Lexington and Concord, the Rebels Tory-hunting Committee of Inspection summoned Samuel, interrogated him abouthis Tory beliefs, and condemned him as inimical to the Liberty of America. The committee also found Samuels son Munson guilty of signing a seditious paper, the import of which was that they would assist the King and his vile minions in their wicked, oppressive schemes to enslave the American Colonies; and tending to discourage any military preparations to repel the hostile measures of a corrupt Administration.

Samuel and Munson, suddenly aliens in their hometown, began planning how to get out. By the early fall of 1776, they could stand on the Stamford shore, look across Long Island Sound, and on the gray horizon see the low-lying land where the British flag had flown since the British Army drove the Continental Army out of New York. As Samuel Jarvis told the story, he and his wife and four children escaped by boat to Long Island. Loyalists became a major Connecticut export.

When Samuel Jarvis reached Long Island, he recruited his son Munson and other Tories into the Prince of Waless American Regiment, one of more than two hundred Loyalist military units. Rich and prominent landowners or royal officials organized and commanded Tory regiments, but the soldiers were usually farmers, laborers, craftsmen, and shopkeepers. Munson Jarvis, like Paul Revere in Boston, was a silversmith.

When Stephens militia was temporarily released from active service, he deserted, apparently without telling his Rebel uncle. Stephen promised his father that he was through with the Rebels, which was true, and that he was through with Amelia, which was not. Stephen joined the Tories by following his uncles example. With other young Connecticut men, Stephen rowed across Long Island Sound, went into New York City, and, after service in another unit, joined the Queens American Rangers. They wore forest green uniforms to distinguishthemselves from their comrades in war, the British Redcoats. The Rangers saw themselves as the elite unit among all the Loyalist forces fighting for the king.

in

in