Published by Basic Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address Basic Books, 1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104.

Books published by Basic Books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the United States by corporations, institutions, and other organisations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at Perseus Books, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, or call (800) 810-4145, ext. 5000, or e-mail special.markets@perseusbooks.com.

Cataloguing-in-Publication data for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

INTRODUCTION:

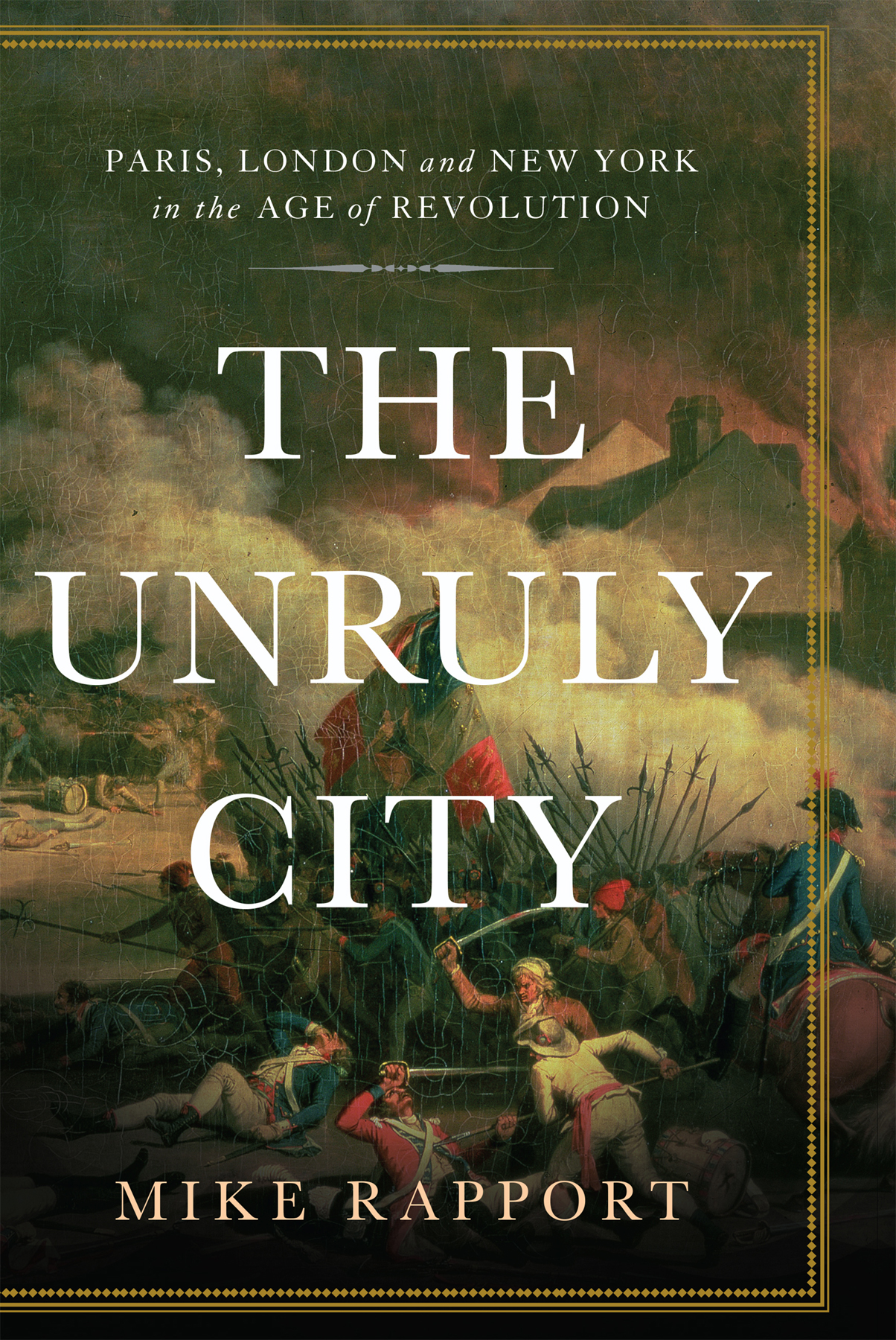

THREE CITIES IN AN AGE OF REVOLUTION

O N A CHILLY winters day, 23 February 1763, sceptical Parisians watched a huge equestrian statue slowly being lowered onto a pedestal at the centre of a vast square on the western edge of their city. The massive artwork, by sculptor Edm Bouchardon, was a masterpiece (or so critics would soon say) and depicted King Louis XV, still with eleven more years to reign, triumphantly on horseback. It was to be the centrepiece of the cobbled expanse of the elegant Place Louis XVnow Place de la Concordewhich spread out at the bottom of the Champs-Elyses. The kingly horseman and square alike were to be monuments to the glory of Frances Bourbon monarchy, celebrating Louis XVs triumphs in the War of Austrian Succession (17401748). The designer of the square was the kings favourite architect, the great neoclassicist Ange-Jacques Gabriel, who trumped fierce competition with his choice of location and plan.

The most imposing sight on Place Louis XV was Gabriels two colonnaded, symmetrical palaces built in Greco-Roman style in warm golden sandstone, overlooking the square from its northern side. Russian historian Nikolai Karamzin would react just as the designers had intended. In April 1790, as his coach rumbled towards the end of the Champs-Elyses, rolling past its idyllic mix of ornamental groves, restaurants, kiosks and music stands, Karamzin leaned out of his carriage window: Your gaze runs on ahead to where a statue of Louis XV rises on a large octagonal plinth surrounded by a white marble balustrade. Approach it and you will see before you the densely shaded paths of the famous garden of the Tuileries, belonging to the great palace: a beautiful view!

Yet in February 1763, the Parisian spectators were not so sure. As the equestrian mass swung from the taught cables of four wooden cranes, the workmen straining at the ropes and pulleys, they bitterly repeated the remark that their king was being held up by four grues, a double entendre meaning both cranes and whores. This Parisian grumbling was aroused by a painful awareness that, just thirteen days previously, the monarchy had signed one of its most humiliating peace treaties. The Treaty of Paris had ended the Seven Years War, one of the most devastating global conflicts of the eighteenth century. For France, it was above all a shattering defeat at the hands of its archenemy, Britain. Most of its empire in India and the Americas had been engulfed by the British, the French army and navy mauled and the honour of the monarchy battered. Louis XV himself, it was widely known, had not led from the front: he had scarcely left the sprawling royal palace and grounds of Versailles, enjoying the company of his intelligent mistress, Madame de Pompadour, and frequenting his selection of courtesanshence the hostile witticisms about grues. The official opening of the Place Louis XV on 20 June that year was timed to coincide with the formal proclamation of the peace. The idea was that Louis XV could be presented as both powerful and a peacemaker, but when set against the scale of the nations military disasters, the statues pretensions rang hollow.

T HIS FRICTION REVEALS an important part of the history, and the present, of great cities. They are at one and the same time places where individuals, social groups and communities live, work and socialise, but they are also centres of authority and powereconomic, political and social. As such, they are not only places where rulers, governments, corporations and institutions actually reside, but also where they inscribe their presence in a visual sense on the cityscape. The buildings and spaces of a city are used by governments, civic institutions and social movements for practical purposes, and they are built, taken over and adapted to suit. In times of political turmoil, public buildings are embellished, vandalised or even destroyed to convey political messages. In times of stability, they become the settled, even mundane, symbols of authority, power, public welfare, freedomor the benevolence and glory of the ruler. In periods of great transition or revolution, transformation in the use, look and even existence of buildings and spaces is one way in which people experience or live the change. Moreover, a physical place may shape the course of an historical event, in the way that terrain affects the outcome of a battle.

For all these reasons, a citys spaces and places are contested, either in the sense of who actually has control of the bricks and mortar or in terms of what these places signify, as the Parisian reaction to the grandiose statue of Louis XV showed. As the royal likeness was eased into place in 1763, it would be wrong to view the coarse jokes among the onlookers as an early stirring of popular, revolutionary hostility (it would take more than a generation for such grumbling to develop into anything resembling that, in 1789). It does show, however, that, try as it might, no regime can entirely control the political messages that a place, a building or an embellishment is meant to transmit. And the political conflicts that arise from the control, adaptation and use of buildings and open spacesthe palaces, squares, parks, churches, taverns, coffeehouses, streets, prisons and so onare never more intense and violent than in times of revolution.

This book is about how three cities, Paris, London and New York, became such sites of struggle in a revolutionary age, that of the American and French Revolutions. It explores, in particular, how, in all the political ferment of the later eighteenth century, the spaces and buildings in these cities both symbolically and physically became places of conflict, how the cityscape itself became part of the experience of revolution and may even have helped shape its course. Revolutionaries in New York and Paris and radicals in London used particular locations and buildings to mobilise their supporters, to demonstrate or debate and to move against the existing order.

Yet the upheavals were not just political revolutions but cultural ones as well: through their ideological struggles and attempts to create new political orders, or reform the old one, radicals and revolutionaries used the cityscape to convey their messages, hopeful, threatening and stirring. In the American and French Revolutions, this certainly involved a hefty dose of iconoclasm: pulling down statues, chiselling away political symbols from public buildings, changing street names and, in the French case, destroying religious emblems. Yet it also involved constructing, embellishing and creating: converting old buildings for new political purposes; carving new mottoes and motifs onto older sites, or, in the cut and thrust of revolutionary politics, hastily painting them on; surmounting buildings with emblems such as liberty caps; raising liberty poles; and using the open spaces of the metropolis to hold revolutionary festivals or public meetings to demonstrate political unity and transmit political messages to the massed ranks of citizens. These were all ways in which revolutionaries and radicals sought to rally people to their cause and to implant the values of the new civic order in the hearts and minds of people as they went about their daily lives. In the words of one historian of the cultural history of revolutions, it was an exercise in regeneration through the everyday, in which the city became the canvas for the cultural revolutions and the scene of the bitterest confrontations between the supporters of the old order and the new. To a large extent, the eighteenth-century battle for political emancipation hinged on control of these spaces, not only in a strategic sense, important though that could be, but also because it determined whose ideas, whose messages, whose authority was disseminated among the people of the metropolis.