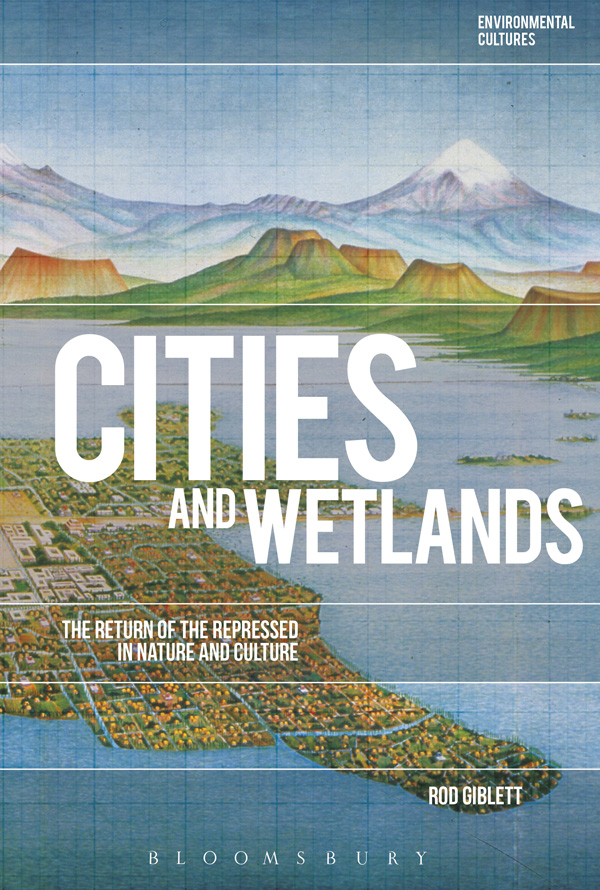

Cities and Wetlands

Cities and Wetlands

The Return of the Repressed

in Nature and Culture

Rod Giblett

Bloomsbury Academic

An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

To Lawrence Buell

Contents

I love wetlands and I live in a city; I love cities and I lived by a wetland for twenty-eight years, for the past five of which I was writing the bulk of this book. This wetland was on the outskirts of a city until the city swamped the surrounds of the wetland and I moved on to another city without many wetlands. I now live in an inner city and not by a wetland. Unlike many of the wetlands destroyed by cities, the wetland by which I lived has not been destroyed. The relationship between cities and wetlands is fraught and they are even inimical to each other: where the city is now, there the wetland was once; where the wetland is now on the outskirts of the city, the city, or its suburbs, soon will be; where the restored, rehabilitated, or artificial wetland is in the city, a wetland or wasteland once was.

Wetlands are vital for life on earth, including human and nonhuman life. The leading intergovernmental agency on wetlands states that

they are among the worlds most productive environments; cradles of biological diversity that provide the water and productivity upon which countless species of plants and animals depend for survival. Wetlands are indispensable for the countless benefits or ecosystem services that they provide humanity, ranging from freshwater supply, food and building materials, and biodiversity, to flood control, groundwater recharge, and climate change mitigation. Yet study after study demonstrates that wetland area[s] and [their] quality continue to decline in most regions of the world. As a result, the ecosystem services that wetlands provide to people are compromised. (Ramsar Convention Bureau, online)

Yet more than the mere providers of ecosystem services, wetlands are habitats for plants and animals, and homes for people. They are also principally under threat on the outskirts of cities where they are drained and filled to create sites for more homes for more people. The relationship between cities and wetlands is fraught, to say the least. Cities and Wetlands traces the relationship between cities and wetlands and calls for reconciliation between them so that they might coexist, if not live together bio- and psychosymbiotically (see Giblett, 2011).

To elaborate on the title of Cities and Wetlands and to locate it within its primary traditional disciplines, it is about cities and wetlands in history and literature. It builds on the previous work of others in these fields, such as Mumfords classic The City in History and Lehans recent The City in Literature. Cities and Wetlands might have been entitled Cities and Wetlands in History and Literature, though this title would have situated the book in the past and in two disciplines alone, whereas it is also concerned with the present and the future, and with other disciplines, principally geography and environmental cultural studies.

To elaborate on its subtitle, The Return of the Repressed in Nature and Culture, Cities and Wetlands is also about the repression of wetlands by cities in the past and present, and about the return of repressed wetlands in culture and nature in the present and for the future. Cities and Wetlands both returns the repressed wetlands to present consciousness and is about the return of repressed past wetlands in the past and the present. It might have been subtitled The Return of the Repressed inthe Past, Present, and Future. The book is in part about cities and wetlands in environmental cultural studies, geography, history and literature, the repression of wetlands by cities, and the return of repressed wetlands in culture and nature. To locate it within its transdisciplines and theoretical framework, Cities and Wetlands is an environmental cultural study conducted broadly within the transdisciplinary environmental humanities.

A book about cities and wetlands would have been a very short and slim one indeed if it had merely related the early history of various cities set in swamps or marshes and their later filling or draining, dredging or canalizing of those wetlands. The scope of Cities and Wetlands is much wider as it considers the return, both literally and metaphorically, in both nature and culture, of the repressed wetlands on, or in, which the city was built. It might have been subtitled The Return of the Repressed in People and Place. This return occurs in fact when, for example, the leveed wetlands of New Orleans were broken in the aftermath of hurricane Katrina and took the city back to its wetland beginnings, or when Venice has a high tide, or acqua alta, that brings up the waters below.

Katrina is a salutary instance of the need to think the cultural and natural together. In particular, it points to the need to think industrial capitalism and its technologies, weather, climate, cities, floods, rivers, and wetlands as intertwining and interrelated entities and agents. Katrina is a salutary instance of the cultural and natural operating together in and as one single catastrophe of history as viewed by the Angel of History, as Benjamin ([1940] 2003: 392) put it, looking back over the course of time. Katrina is also one single catastrophe of geography as viewed by the Angel of Geography looking over the expanse of space in the will to fill and the drive to drain or reclaim wetlands. Rather than a series of catastrophes proceeding one after the other through history, Benjamins Angel of History sees one single catastrophe of history (392). This single catastrophe, however, occurs not only in time, in history, but also in space, in a place, in geography. As well as the Angel of History, the Angel of Geography sees one single catastrophe of wetlands dredged, filled, and so reclaimed, cities set in them and cities being re-reclaimed by them in storms and floods. In the case of Katrina, the catastrophe of history and geography is tied up with the creation, destruction, and re-creation of New Orleans in its swampy location on the Mississippi delta.

The city thus can, and sometimes does, revert to wetland in a return of the repressed wetland in a process of displacement and transformation, like its psychoanalytical counterpart. Water is not in the place it is supposed to be in the city, and the city is transformed back into the wet land it once was in what I call the return of the geographical and historical repressed wetland, of the spatial and temporal repressed, of the lost and forgotten wetland. Just as in psychoanalysis the repressed always returns, so too in city the repressed always returns as the repressed is never totally suppressed or destroyed. Active traces of the city repressed, as much as the psychological repressed, always remain to be reactivated and return naturally and culturally. The return of the repressed wetland also occurs figuratively, such as in the fascination with, and horror of, the dark underside of the sewers and slums of the city figured in wetland tropes. Cities and Wetlands might have been subtitled The Return of the Repressed inFact and Figure.

Tropes are the dreams of speech, as Nabokov (1971: 328) called them, and dreams are the royal road to the unconscious, as Freud ([1899] 1976: 769) defined them. Tropes are the royal road to the unconscious of speech, and writing; tropes for the dark and sewery underside of the city are the royal road to the wetland unconscious, and repressed, of the city. The repressed swampy or marshy beginnings and subsequent history of wetland cities, or aquaterrapolises, return in their speech and writing about it. The trope both represses that history and returns to it; the trope not only masters the absence of the lost wetland in common with all speech and writing, but also enacts the return of the repressed.