About the Author

John Julius Norwich is the author of magisterial histories of Norman Sicily, the republic of Venice and the Byzantine empire. He has also presented some thirty historical documentaries for BBC television.

Other titles of interest published by

Thames & Hudson include:

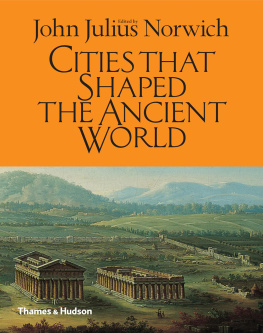

Cities That Shaped the Ancient World

Ancestral Journeys: The Peopling of Europe from the First Venturers to the Vikings

The Romans Who Shaped Britain

Digging for Richard III: How Archaeology Found the King

See our websites

www.thamesandhudson.com

www.thamesandhudsonusa.com

CONTENTS

JOHN JULIUS NORWICH

MARGARETE VAN ESS

ROBIN CONINGHAM

IAN SHAW

BILL MANLEY

TREVOR BRYCE

JOAN OATES

JULIAN READE

HENRY HURST

BETTANY HUGHES

W. J. F. JENNER

ALAN B. LLOYD

ROBERT MORKOT

MARTIN GOODMAN

NIGEL POLLARD

SUSAN TOBY EVANS

SIMON MARTIN

JOHN JULIUS NORWICH

DORIS BEHRENS-ABOUSEIF

BARNABY ROGERSON

VICTOR C. XIONG

DORIS BEHRENS-ABOUSEIF

DORIS BEHRENS-ABOUSEIF

MICHAEL D. COE

JOHN JULIUS NORWICH

DORIS BEHRENS-ABOUSEIF

COLIN THUBRON

CHRIS JONES

WILLIAM L. URBAN

ADAM ZAMOYSKI

JOHN JULIUS NORWICH

CHARLES FITZROY

PATRICK DARLING

BARNABY ROGERSON

BRIAN S. BAUER

SUSAN TOBY EVANS

MALYN NEWITT

CHARLES FITZROY

JASON GOODWIN

EBBA KOCH

STEPHEN P. BLAKE

FRANCES WOOD

LESLEY DOWNER

COLIN AMERY

SIMON SCHAMA

FELIPE FERNANDEZ-ARMESTO

A. N. WILSON

CHARLES FITZROY

THOMAS PAKENHAM

COLIN AMERY

COLIN AMERY

MISHA GLENNY

MAGNUS LINKLATER

ORLANDO FIGES

PHILIP MANSEL

A. N. WILSON

MISHA GLENNY

RORY MACLEAN

SIMON SCHAMA

FELIPE FERNANDEZ-ARMESTO

JANE RIDLEY

RORY MACLEAN

JAMES CUNO

KEVIN STARR

FELIPE FERNANDEZ-ARMESTO

JOHN KEAY

JAN MORRIS & ALEXANDER BLOOM

ELIZABETH JOHNSON

ELIZABETH FARRELLY

LESLEY DOWNER

JOHN GITTINGS

JOHN JULIUS NORWICH

It is one of the great paradoxes of history that towns and cities could be said to be born of agriculture. Before man learnt to till the fields, he was a hunter; and the early hunters were nomads they had to keep on the move, following their prey wherever it might lead them. Even when prey was plentiful, it made sense that one family of hunters should not live too close to the next. Agriculture, on the other hand, calls for settled habitation in more durable structures, and for cooperation. With the advent of farming, in 8000 BC or thereabouts, architecture was born; people built themselves houses in groups near the land they cultivated. Then, gradually over the centuries, as larger communities came together and greater investment was made in individual buildings, a multiplicity of functions emerged within settlements: there were temples in which to sacrifice to the gods; a palace from which a ruling elite governed; storerooms for the accumulated agricultural produce; baths and open spaces where people could gather and refresh themselves after their labours; and walls for defence. Demand for prestige goods would stimulate trade and exchange, though that in turn would probably depend on the proximity of the sea or a great river. And so the village became the town, and the town if large and important enough eventually became the city.

The greatest of these cities form the subject of this book. The first section deals with those of the ancient world, extending to AD 100 or thereabouts. Of the very earliest Uruk in Mesopotamia, for example, which can be claimed as the first true city in the world, or Mohenjo-daro in the Indus Valley relatively little is left above ground. Some fragmentary texts may survive; otherwise we have to rely for our knowledge on the archaeologists spade alone. The civilization of ancient Egypt, represented here by Memphis and Thebes, is the oldest culture of which, thanks to its surviving monuments, paintings, carvings and inscriptions, we can begin to form a distinct idea in our minds. Of Athens and imperial Rome, too, there is fortunately enough still standing together with a considerable body of superb literature to enable us to build up an even clearer picture of what these cities looked like, and of the sort of life that was lived by their inhabitants. Jerusalem is, I think, a special case. It possesses no majestic architecture of the classical period on the scale of Greece or Rome, but its primary position in both the Jewish and Christian (and later also Islamic) religions and the wealth of great literature that they have left behind have given it despite its unhappy history an aura possessed by no other city in the world.

Next we pass on to the cities that had their finest flowering during the first millennium of the Christian era. Here we can extend our gaze to a larger world. Two of our great cities Tikal and Teotihuacan are in Central America. Another is Chinese: Changan, the capital of the dazzling Tang dynasty. No fewer than four are Islamic throwing into sharp relief the superiority of the Arab-Moorish civilizations during those centuries that in northern Europe are not surprisingly known as the dark ages. Christianity is represented by one city only: Constantinople. It appears late on the historical scene, having been founded by the emperor Constantine the Great as recently as AD 330; but from the moment of its foundation it was the capital of the Roman empire, and it dominated the eastern Mediterranean for the best part of a thousand years until the catastrophe of the Fourth Crusade in 1204.

In the medieval period which, for the purposes of this book, spans the years from around AD 1000 to 1500 our net is cast wider still. It spreads north to Lbeck and the cities of the Hanseatic League; south to Cairo and Palermo, Benin and Timbuktu; east to Krakw, Samarkand and Angkor; and west to two more great cities of pre-Columbian America, Aztec Tenochtitlan later buried beneath present-day Mexico City and Cuzco, the 2-mile-high capital of the extraordinary Inca people. It is impossible to compare these cities with each other, if only because of the immense distances both geographical and cultural which extended between them. The world in the Middle Ages seemed of unimaginable size, with most of it still shrouded in mystery. Journeys were slow, long-distance communications almost non-existent, navigation rudimentary, since longitude was still incalculable. Outside Europe, few of the cities on our list would ever even have heard of one another.

The very end of the 15th century, however, marks a sudden and spectacular leap forward. In 1492 Christopher Columbus discovered or perhaps rediscovered the New World; and only a year or two later Vasco da Gama was to open up the Cape Route to the Indies from Europe. Henceforth a ship could be loaded in London or the Hanseatic ports and unloaded at its final destination in Bombay or the Spice Islands; no longer was it necessary to risk valuable cargoes in the pirate-ridden Red Sea or Persian Gulf, nor yet to entrust them to the shambling camel caravans that might take three or four years to cross the steppes of Central Asia. If this was bad news for the Mediterranean, which now seemed fated to become little more than a backwater, it was worse news still for Venice and the other great commercial ports of the Middle Sea, which had already been rocked by the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks in 1453. Spain and Portugal, on the other hand, rejoiced particularly after the Borgia Pope Alexander VI had, by the Treaty of Tordesillas, drawn a line on the map and divided up the new-found South American continent between them.