THE KINGDOM IN THE SUN

1130-1194

JOHN JULIUS NORWICH

Faber and faber

This edition first published in 2010 by Faber and Faber Ltd Bloomsbury House, 74-77 Great Russell Street London

Printed by CPI Antony Rowe, Eastbourne

All rights reserved John Julius Norwich, 1970

The right of John Julius Norwich to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

isbn 978-0-571-26044-7

For my mother

CONTENTS

Introduction

Acknowledgements

part one:

morning storms

The Cost of the Crown

Revolt in the Regno

The Imperial Invasion

Reconciliation and Recognition

part two:

the noonday kingdom

Roger the King

Enemies of the Realm

The Second Crusade

Climacteric

part three:

the lengthening shadows

The New Generation

The Greek Offensive

Realignments

Murder

The End of a Reign

part four:

sunset

The Counsellors of Unwisdom

The Second Schism

The Favourite's Fall

The English Marriage

Against Andronicus

The Resplendent Shadow

The Three Kings

Nightfall

Appendix:

The Norman Monuments of Sicily

Bibliography

In Sicily one might find, all within a few miles of each other, the castle of some newly-created baron, an Arab village, an ancient Greek or Roman city and a recent Lombard colony; in one and the same town, together with the native population, there might be one quarter of Saracens or Jews, another of Franks, Amalfitans or Pisans; and among all these various peoples, there would reign that peaceful tranquillity which is born of mutual respect.... The bells of a new church, the chanting of the monks in a new abbey, would mingle with the cry of the muezzin from the minaret, calling the faithful to prayer. Here was the Latin Mass, modified according to the Gallican liturgy; here, the rites and ceremonies of the Greeks; here, the rules and disciplines of the Mosaic Law. The streets, squares and markets revealed a marvellous variety of costume; the turbans of the orientals, the white robes of the Arabs, the iron mail of the Norman knights; differences of habits, inclinations, celebrations, practices, appearances: infinite and continuous contrasts, which yet came together in harmony.

I. la lumia,

History of Sicily under William the Good, 1867

Just over sixty years ago, in the preface to his own history of the Norman Kingdom of Sicily, M. Ferdinand Chalandona writer, heaven knows, not normally given to excessive dramatisation noted that an unhappy fate seemed to hang over all would-be historians who tackled the subject; naming no less than three who, as he delicately put it, had 'prematurely disappeared' before their work was completed. In 1963, to a writer embarking on his first full-scale literary venture with an already distinct sensation of having bitten off more than he could chew, it was hardly an encouraging reminder; and there have been many moments in the past seven years when the end of my labours did indeed seem impossibly remote. It is therefore with more surprise than anything else that I now find that I have come to the end of my story.

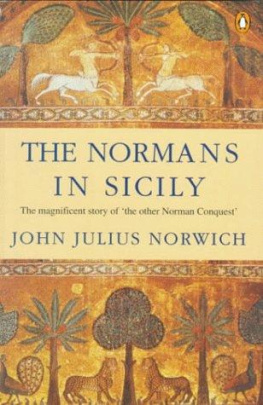

This second volume of the Hauteville saga is self-contained, in the sense that it presumes the reader either not to have read its predecessor or, if he has, to have forgotten it. It does, however, take up the tale where The Normans in the South left offat King Roger's coronation on Christmas Day 1130 in Palermo Cathedraland carries it through to that other, blacker Christmas when the most coruscating crown of Europe was laid, by an English archbishop, on the head of one of the most loathsome of German Emperors. The sixty-four short years that separated those two eventsless of a span than we have the right to expect for ourselvesconstituted the whole lifetime of the Kingdom; they also provided the island with its golden age when, for the first and only time in history, the three great racial and religious traditions of the Mediterranean littoral fused under the southern sun and crystallised into that flashing, endlessly-faceted jewel that was the culture of Norman Sicily.

It isor at least it should beabove all else the surviving monuments of this culture that draw us to Sicily today; monuments which miraculously translate the Hautevilles' political achievement into visual terms and in which Western European, Byzantine and Islamic styles and techniques effortlessly coalesce in settings of such magical opulence that the beholder is left dazzled and incredulous. I have therefore done my best to make this book not only an account of people and events but also a guide to these monuments. The most important of them I have described in detail, not in a separate and indigestible chapter but at suitable points in the course of the narrative, so as to relate them as directly as possible to their founders or to the circumstances surrounding their construction. The rest, graded according to the time-honoured star system and furnished with page references where appropriate, I have relegated to a list in the appendix. This, I like to think, records every item of Norman work worthy of the name still surviving in Sicily; it is certainly the most comprehensive one yet to appear in this country.

But the history of Roger's Kingdom is something more than a background to its works of art, however memorable they may be. It is also one of the tragedies of Europe. Had it lasted, had it succeeded in preserving those principles of toleration and understanding to which it owed its existence, had it continued to serve as a focus of intellectual enlightenment in a blinkered and bigoted age and as the cultural and scientific clearing-house of three continents, then ours at least might have been spared much of the suffering that awaited it in the centuries to come, and Sicily might have been the happiest, rather than the most ill-starred, of Mediterranean islands. But it did not last; and this book has had to tell not only of how it flourished, but also of its failure and its fall.

One further point, which I have already made in the introduction to The Normans in the South, must I think be re-emphasised here: that this is in no sense a work of scholarship. When I started it I knew no more than anyone else about Sicily or the Middle Ages; and now that I have finished I have no plans to write any more about either subject again. Here, quite simply, is a piece of historical reportage, written for the general public by one of their own numberone whose sole qualifications for the task were curiosity and enthusiasm. I hand over my typescript now with the same hope that I had when I began: that these emotions may prove infectious, and that others may grow, as I have grown, to loveand to lamentthat sad, superb, half-forgotten Kingdom, whose glory shone ever more golden as the sun went down.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Much of Chapter 2 of this book was written during a fortnight in June, 1967, when the outbreak of war in the Middle East left me largely through my own incompetencestranded in the British Embassy, Khartoum; and I should like to thank Sir Robert and Lady Fowler for the kindness they showed, at an appallingly difficult time for themselves, to an uninvited, unexpected and virtually unknown guest. More thanks wing off to the Languedoc, where Xan and Daphne Fielding saw me so splendidly through Chapter All the other chapters first saw the light in the London Library, of which I seem by now to have become part of the furniture. To Stanley Gillam, Douglas Matthews and every member of the staffespecially those who have to keep calling me down to the telephonemy gratitude is, as always, boundless.

Next page