Contents

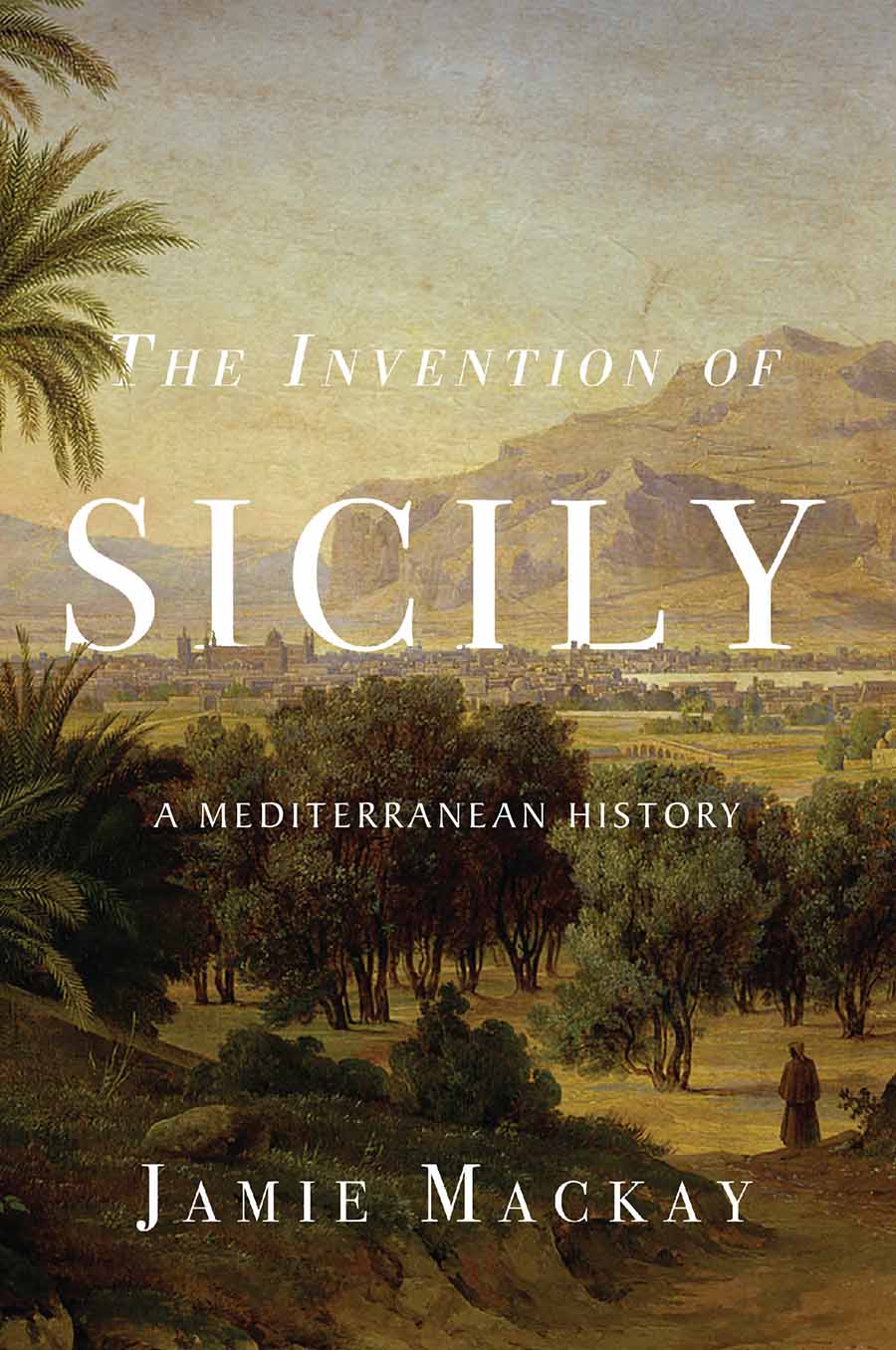

The Invention of Sicily

The Invention

of Sicily

A Mediterranean

History

Jamie Mackay

First published by Verso 2021

Jamie Mackay 2021

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-78663-773-4

ISBN-13: 978-1-78663-776-5 (US EBK)

ISBN-13: 978-1-78663-775-8 (UK EBK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Mackay, Jamie Alexander Calum, 1990 author.

Title: The invention of Sicily : [a Mediterranean history] / Jamie Mackay.

Description: London ; New York : Verso, 2021. | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Summary: In this riveting, rich history, Jamie Mackay peels away the layers of this most mysterious of islands. It is a story with its origins in ancient legend that has reinvented itself across centuries: in conquest and resistance. Inseparable from these political and social developments is the nations cultural patrimony Provided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021017521 (print) | LCCN 2021017522 (ebook) | ISBN 9781786637734 (hardback) | ISBN 9781786637765 (US ebk) | ISBN 9781786637758 (UK ebk)

Subjects: LCSH: Sicily (Italy) History.

Classification: LCC DG866 .M317 2021 (print) | LCC DG866 (ebook) | DDC 945.8 dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021017521

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021017522

Typeset in Fournier by MJ & N Gavan, Truro, Cornwall

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY

Contents

1. The Liquid Continent (800 BC826 AD)

The Colonies of Magna Graecia, Hellenistic Culture, Roman-Byzantine Occupations

2. The Polyglot Kingdom (8261182)

Life in the Emirate, Norman Conquest, Hybrid Architecture

3. The Anti-Christ of Palermo (11821347)

An Emperor-King, the Peaceful Crusade, Sicilys War of Independence

4. A Silent Scream (13471693)

Black Death, the Spanish Inquisition, Spells and Incantations

5. Decadence and Parlour Games (16931860)

Baroque Towns, Legendary Bandits, Folk Politics

6. A Revolution Betrayed (18601891)

Italian Unification, the Origins of the Mafia, the Paradoxes of Liberalism

7. A Modernist Dystopia (18911943)

Political Corruption, Fascism and Futurism, a Colonial Administration

8. The Return of the Mafia (19432013)

The American Connection, Concrete Cathedrals, Bunga Bunga

Introduction

The Limits of the West

The atlases say that Sicily is an island, and that might well be true. Yet one has some doubts, especially when you think that an island usually corresponds to a homogenous blob of race and customs. Here everything is mixed, changing, contradictory, just as one finds in the most diverse, pluralistic of continents.

Gesualdo Bufalino, novelist

Ive always held that Sicily represents many problems, and many contradictions, that are not just Italian, but are also European in scope to some extent this island serves as a metaphor for the entire world.

Leonardo Sciascia, novelist and essayist

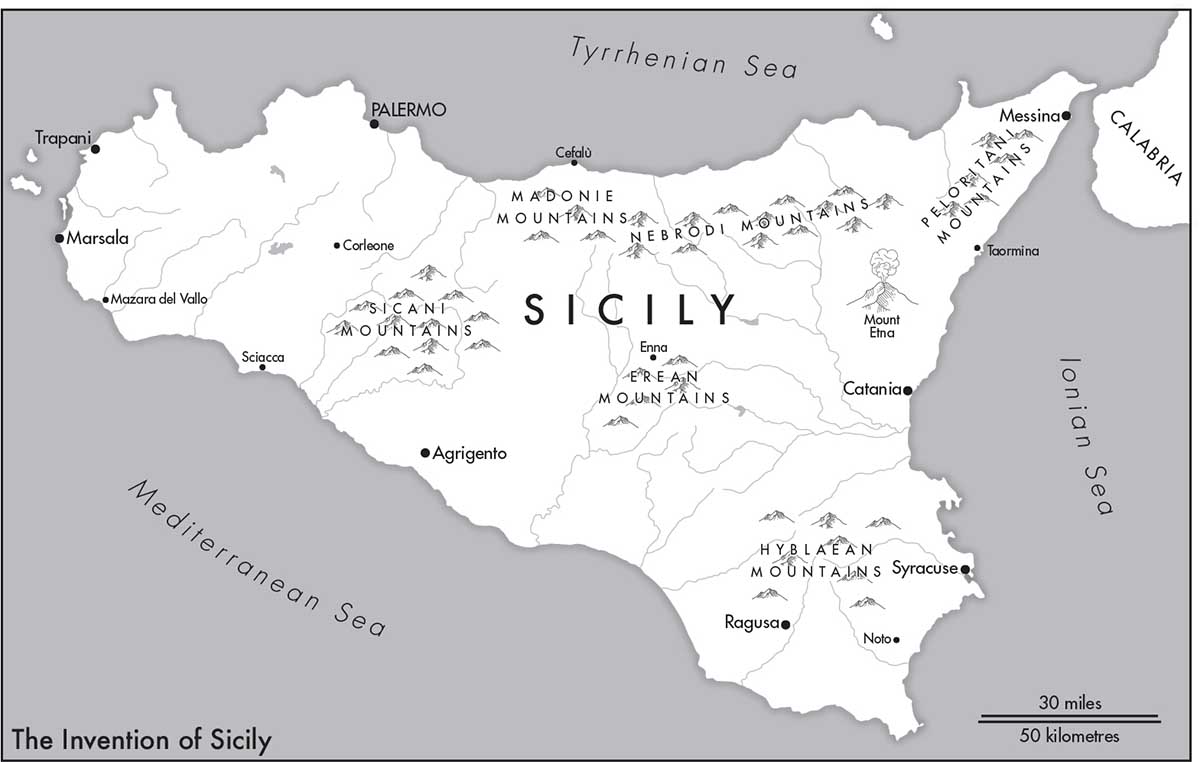

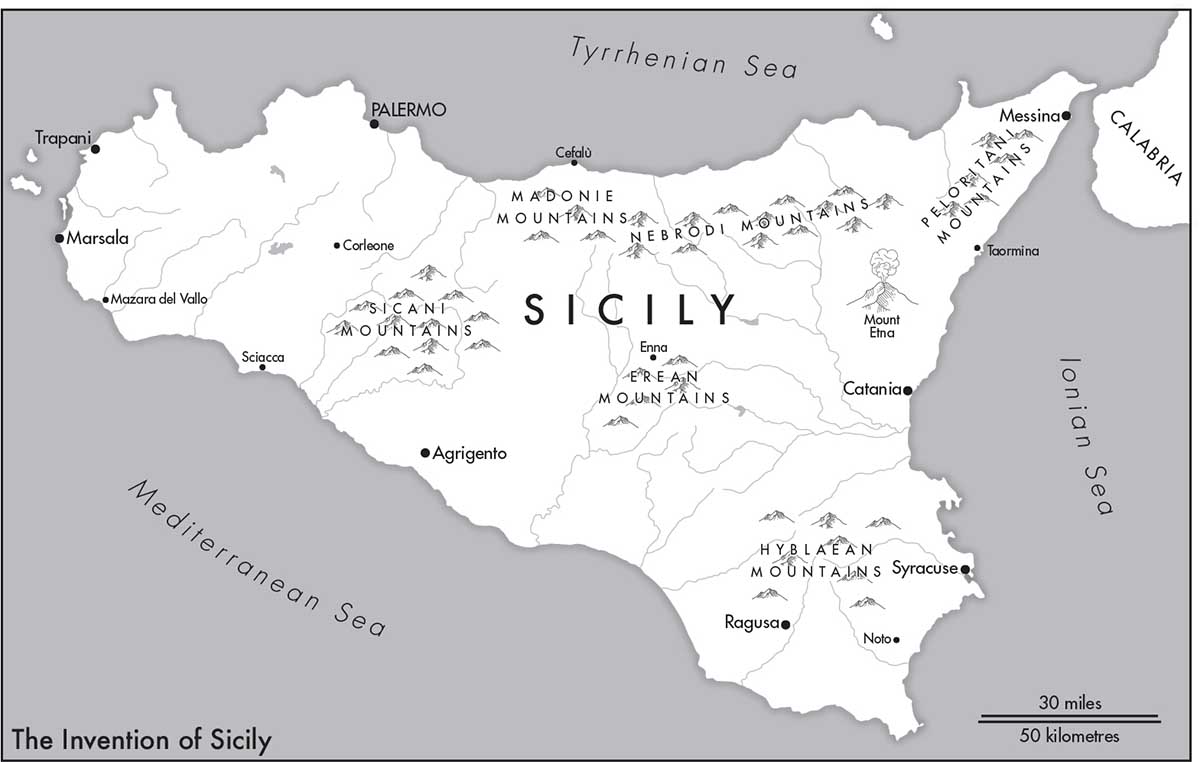

Sicily is one of the worlds most important borderlands. Situated at the very centre of the Mediterranean, equidistant from Rome and Tripoli, closer to Tunis than Naples, the island marks the frontier between southern Europe and North Africa. For centuries people have viewed this volcanic landmass as a point of division between civilised and barbarian peoples, Christianity and Islam, and most tentatively and destructively of all, between white and black races. Sicily has been surrounded by almost constant conflict. Ever since the third century BC, when the consuls of the Roman Republic demarked the island as the frontline of the Punic Wars, it has come to separate the Western world from what lies beyond. In the medieval period, Catholic orders used Sicily as a base from which to launch crusades against Muslims in Jerusalem and, in later centuries, against the Ottomans. In the twentieth century, Mussolini imagined the island as the centre of his Mediterranean empire and, after WWII, the Americans built NATO airfields and submarine bases along the south coast to protect their interests in the Middle East. Today, right-wing populists continue to perpetuate this divisive logic by presenting Sicily as the site of an invasion by refugees, who they claim pose a threat to a European way of life.

Borders, though, are rarely as definite as they appear on maps. The longer you spend living around them, the less sense these kinds of simplistic divisions make. Frontiers are places where identities take on absurdly definite forms, in barbed wire fences and vigilante patrols. At the same time, theyre places where boundaries between different cultures break down. Sicilian history is white, Christian and Western, certainly, but it has also been, and still is, black, Arab and Muslim among other things. Such ambiguities are present everywhere, but they are particularly visible on the shores of the Mediterranean. This is what makes the region so exciting. Its also what makes it difficult and, for some, uncomfortable. In a recent book, the author Kapka Kassabova describes the frontier between Bulgaria, Greece and Turkey rather poetically as a place where the divisions between self and other, intention and action, dreaming and waking dissolve.gardens. The island itself is a kind of mirage which only becomes visible at the intersections of these complex cultural exchanges; precisely where the divisions between historical eras, identities and nations are at their most obscure. For the uninitiated this can be disorienting. During a visit to Sicily in 1910, Sigmund Freud took a carriage from Palermo, the capital, to Agrigento on the south coast. When he reached Syracuse, the islands most important ancient city, he was impressed by the art and architecture. Yet something disturbed him about this exotic, stiflingly hot place. Sicily, he reflected, was a benchmark of Western civilisation, but at the same time it was also wild and somehow dangerous. It was both inside and outside Europe. Shortly after returning to Vienna, the psychoanalyst was struck by an intense bout of paranoia and began to doubt his professional vocation. Later in life he came to view Sicily as a place where the unconscious and conscious minds become muddled: a limit point of the Ego itself.

Of course, Sicilians do not experience their homeland in such neurotic, fragmented terms. For the islanders themselves, life is and has always been characterised by the almost constant exchange of people and ideas across and beyond the Mediterranean. The enduring implications of this became clear to me in 2014 when I found myself talking with Leoluca Orlando, the mayor of Palermo, at a public event. Id just moved to the city, and at the time I was looking to better understand how new migrants from Asia and Africa were integrating into the local community. Orlando insisted that to even begin to answer that question, and make some sense of the larger issue of how Sicily relates to the West, it would not be enough to think in terms of decades alone. Instead, he insisted, one has to engage seriously with the cosmopolitan roots of the islands history, with a flow of people that began in the ancient world and which, despite various interruptions, has always had an impact on Sicilian identity. I was immediately struck by the mayors use of the word cosmopolitan. In the English-speaking world, this word often serves as a euphemism for neoliberal globalisation. Its a concept that a certain privileged elite, who have the resources to travel for leisure, not to mention the right passport, use to voice their frustrations with any form of localised, territorialised politics that might seek to limit their power. When I suggested this to Orlando, he retorted that this was just one rather hollow meaning of the term. For most Sicilians, he continued, cosmopolitanism is an