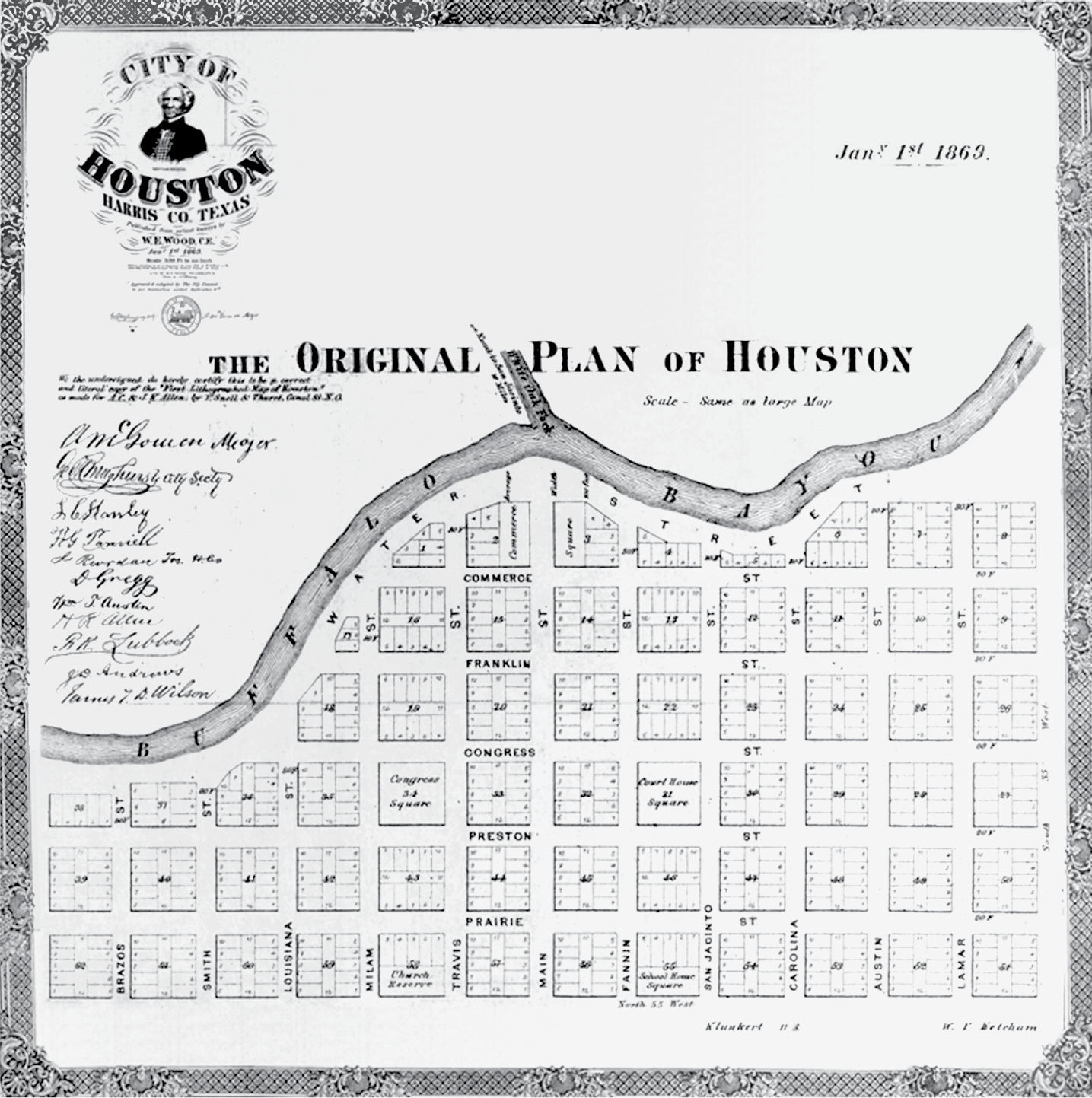

Original plan for the city of Houston, A.D. 1863

1

WHY CITIES?

As an archaeologist, my favorite place in Rome is not the Colosseum or the Forum. Its the ancient trash dump of Monte Testaccio. Right in the middle of the city, it is a giant mound of broken pottery where the ancient Romans threw away the containers used to ship wine and olive oil all around the Mediterranean. Each of those vessels was about half the height of a person and made of coarse clay that would have roughed up a stevedores hands. Their odd shape of two handles and a pointy base made them good for packing into a ships hold or standing upright on a sandy shoreline but very inconvenient for much else. After a cargo of them arrived at its destination on the bustling shores of the Tiber at the very heart of the Roman world, a few were reused and a few were recycled. Mostly, people poured out the contents and threw the containers away. Over the centuries, the pile of discards grew, with the result that one of the famous hills of Rome is actually not a hill at all but a human constructiona landfill, essentially. Today Monte Testaccio is topped by trendy nightclubs and has been endlessly mined for construction, but there are still the remains of twenty-five million ancient containers poking up from the vegetation of the hillside.

Now consider a very different metropolis. My favorite part of Tokyo? The backside of the Tsukiji fish market, the part that tourists dont visit. Tsukiji is enormous, and the passageways are crowded with plastic buckets and barrels teeming with every kind of creature that you can imagine from the briny deep. Crabs attempt to crawl their way out of baskets, little fish are piled up in ice buckets, and great slabs of tuna glisten under the klieg lights. The market is open to everyone, with chefs and restaurant owners jostling with homemakers for a clearer view of the days catch. Its a world without friendly chitchat, punctuated by the dangerous darting movements of souped-up forklifts that dodge their way in and out of the building and heap up their discards out back. Behind the market is an enormous dump of plastic-foam shipping boxes used to transport the globally sourced tuna, squid, and shrimp from each mornings auctions. The pile of containers is taller than a two-story building and so large that it is continually cleared by bulldozer. Some of the cartons are trampled and broken in the process, with bits and pieces that spill farther into the passageway. In between the endless runs of machinery, merchants and their helpers come to pick through the heaps of box fragments. Sorting through the pile to find ones that arent too broken, they carry them off to repack with fish or whatever else theyre selling.

Ancient Rome and modern Tokyo are literally a world apart, but if we stand back and look at them as cities, they have identical characteristics. In addition to markets and trash, there are multistory buildings, long streets, sewer pipes, water mains, public squares, and a downtown zone of financial institutions and government offices. There are a thousand varieties of sounds and smells, competing with the weather and daylight that frame the skyline of the built environment. There are crowds of peoplerich, poor, young, old, female, male, gay, straight, trans, abled, disabled, employed, students, jobless, residents, and visitors. Production and consumption opportunities are scaled up in cities to provide not only more things but also more things per person, a completely ironic abundance given that urban residences tend to be much smaller than their rural counterparts. In the midst of so much abundance, the only solution is to cycle through possessions faster, turning everything into trash.

Its the act of discard that provides the most telling evidence of urban activity, whether its a broken potsherd from two thousand years ago or a fragment of a plastic crate that was shattered this morning. Once you start to look for the concentrated detritus of your own urban life, its everywhere: in the trash cans that bear the proud logo of the downtown business improvement district; in the Dumpster parked outside a building that signals a renovation taking place inside; in the garbage truck that obstructs your commute; in the legions of sanitation workers employed to sweep the streets and subways and haul away the accumulations of discards. Trash has a familiar rhythm and concentration. Holidays bring a hangover of extra-full trash bins; parades and festivals and summer weekends in the park are witnessed through their aftermath of overflowing containers. Whether directly or by proxy, an urban obsession with trash is everywhere, and once you start to look, you wont be able to stop seeing it. Congratulations! Youre an archaeologist.

Moving your gaze upward, or to the side, you might notice that its not just trash that silently tells a story of urban life. Your own metropolis, even if its new, has many traces that reveal its history before you moved through its streets. Maybe its a bolt hole in the sidewalk where a telephone booth used to stand, or an out-of-use railroad track now embedded in the asphalt of a city street. Maybe its a building that has been updated once or twice, resulting in the pastiche of a Victorian facade with mirrored glass windows, or a modernist concrete structure fronted by flowers and cheerful painted windowsills. And maybe its a newly cut ditch in the street where you can see the layered pavements of prior years right up to the present. Buildings and streets and parks serve as a living map of variable time, a collection of structures that all exist simultaneously whether they were constructed a millennium ago, in your grandparents time, or last week.