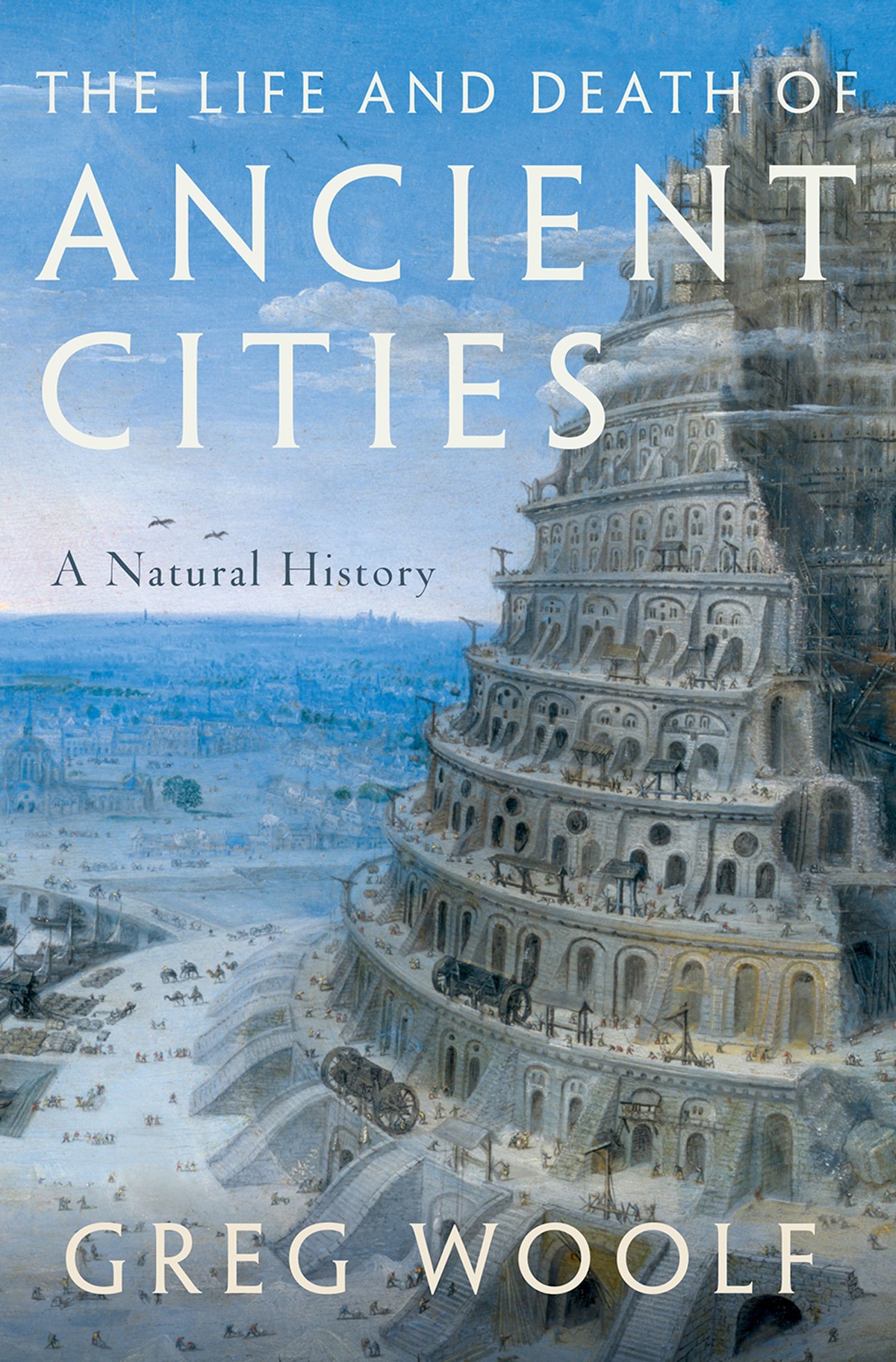

THE LIFE AND DEATH OF ANCIENT CITIES

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

Oxford University Press 2020

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Woolf, Greg, author.

Title: The life and death of ancient cities : a natural history / Greg Woolf.

Description: First edition. | New York : Oxford University Press, [2020] |

Includes index. |

Identifiers: LCCN 2019042392 (print) | LCCN 2019042393 (ebook) |

ISBN 9780199946129 (hardback) | ISBN 9780190618568 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Cities and towns, AncientMediterranean Region. |

UrbanizationMediterranean RegionHistoryTo 1500. |

ImperialismSocial aspectsMediterranean RegionHistoryTo 1500.

Classification: LCC HT114.W66 2020 (print) |

LCC HT114 (ebook) | DDC 307.760937dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019042392

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019042393

For Maud and Ben,

with love, admiration, and gratitude

Contents

Figures

Maps

The ancient world is often celebrated for its cities. This book is not another celebration. Instead it tells the story of how late cities appeared in the ancient Mediterranean world, how small most of them were, and how precarious urban life remained throughout antiquity.

Ancient cities have become grandiose in our imagination. There are several reasons for this. We remain spellbound by the neoclassical monuments of modern metropoleis, many of them capitals of recent empires, like Paris and London, Washington and Berlin, St Petersburg, Madrid and Rio. The ancient world inspired those architectures but was built on a much smaller scale. Our habit of seeing the ancient world through the eyes of its most educated inhabitants, who for centuries were committed to an urban ideal, has not helped. The authors of Greek and Latin literatures were themselves ignorant of how their urban world had arisen, and they projected back into their past a world of grand cities that never really existed. Troy VII was a splendid fortress by the standards of the late Bronze Age, but it covered barely 20 hectares and probably had a population of 5,000 to 10,000 people. The Rome in which Virgil wrote the Aeneid covered nearly 1,800 hectares and had nearly 1,000,000 inhabitants. No wonder their accounts of early first millennium were so anachronistic.

Rome was exceptional. Research conducted over the last thirty years has made clear the tiny scale of most ancient cities. That research has brought together many disciplines. Archaeologists have laboured to date and map early settlements, often disentangling them from the accumulated matter of their successors, and locating them in broader settled landscapes and at the nodes of complicated networks of exchange and migration. Philologists have read ancient texts more and more closely, putting aside modern assumptions about their meaning, looking more closely at their rhetorical and political agenda. Historians have compared ancient Greek and Roman cities with those of other societies from the time before industrial revolutions and demographic transitions changed everything. Most recently historians have engaged with the life sciences, which have taught us so much in recent years about the human animal, about the primate bases of our social life, about ecology and climate. Our new understandings of antiquity depend on a collaboration between the humanities and social science and biology. This book is an attempt to show what that collaboration has achieved so far in relation to ancient cities.

This book begins broad and narrows down in focus. The first part looks at the prehistory of urban growth across the world and follows developments in one corner of itthe Ancient Near Eastto the end of the Bronze Age. Mediterranean urbanism was an offshoot of those developments, and a late growth at that. The second part tracks the emergence and growth of urban networks around the Mediterranean Sea in the first half of the last millennium b.c.e. Some villages were replaced by tiny cities, and the landscapes and societies they organized became connected. The third part follows more brutal histories of connection, the rise of empires and with them the first really great cities of the region. A short fourth part sketches a kind of reversion, in which horizons narrowed and great cities shrank. But cities never disappeared completely, nor the ideas and technologies created in their construction. Those ideas, technologies, and often the actual physical remains of great cities would be recycled in Byzantium, in the Caliphate, and in tiny mediaeval capitals in the west like Aachen, providing material for a whole series of postclassical urbanisms, some of which would be exported to other continents.

The story of ancient Mediterranean urbanism is one episode among many that make up our species urban adventure. Over the last six thousand years, humans have laboured to build cities right around the planet. Cities have been invented several times quite independently, and the results have been surprisingly similar. This is why the broader picture presented in the first part of this book is so important. The first chapters explore what we have in common as a species and argue that we are unusuallybut not quite uniquelywell suited to city life. Some species of animal have evolved to make the most of urban life. Our species is preadapted to it; that is, there are some features of us, features that appeared for quite other reasons, that can be co-opted to make us urban animals. Only by understanding that can we understand the highs and lows of urbanism in the ancient Mediterranean world.

This story could have been told in a variety of ways, and I considered several alternatives before beginning work. One conventional technique is to build a narrative around a series of case studies, something like Knossos, Mycenae, Athens, Syracuse, and so on. A History of Antiquity in a Hundred Cities would have some attractions, bringing out the differences in architectures and planning, providing a scaffolding around which to retell accounts of foundations and sieges, fires and plagues, imperial rebuilding, and so on. But it would inevitably have directed attention to the largest, the most glamorous, and best documented examplesand therefore the most unusual and least typical of cities. A sequence of cases studies might also have obscured the passage of time. Many ancient cities were very ancient indeed. Athens has been continuously occupied for nearly four thousand years. Rome, Naples, Marseilles, and Alexandria are still great cities today, all well over two thousand years old. The history of Mediterranean urbanism is not a succession of cities, but a succession of urban worlds in each of which some of the same cities played key roles. Another approach would have begun from a series of types: the Greek City, the Etruscan City, the early Roman colony, and so on. There have been some successful books of this kind, including the Italian classic