Published by

Oxbow Books, Oxford

Oxbow Books and the authors, 2009

ISBN 978-1-84217-349-7

PRINT ISBN: 978-1-84217-370-1

PRC ISBN: 978-1-78297-353-9

EPUB ISBN: 978-1-78297-352-2

This book is available direct from

Oxbow Books, Oxford

(Phone: 01865-241249; Fax: 01865-794449)

and

The David Brown Books Company

PO Box 511, Oakville, CT 06779, USA

(Phone: 860-945-9329; Fax: 860-945-9468)

or from our website

www.oxbowbooks.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Inside the city in the Greek world : studies of urbanism from the Bronze Age to the Hellenistic

period / edited by Sara Owen and Laura Preston.

p. cm. -- (University of Cambridge museum of classical archaeology monographs ; 1)

ISBN 978-1-84217-349-7

1. Urbanization--Greece--History. 2. Greece--Social conditions--To 146 B.C. 3. Greece-

Antiquities. I. Owen, Sara. II. Preston, Laura, 1972

HT384.G8I576 2009

307.7609495--dc22

2009019507

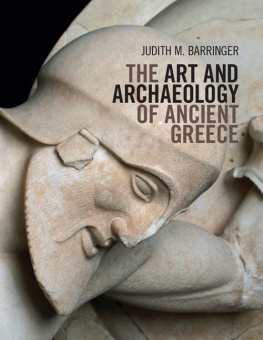

Cover image: View of the Magasin des Colonnes, Delos (photograph by Martin Millett)

Printed in Great Britain by

The Information Press

Eynsham, Oxfordshire

1 Introduction: Inside the City in the Greek World

Laura Preston and Sara Owen

Ancient cities in the Greek world have long been a focus of archaeological investigation. But until relatively recently they have tended to be described rather than analysed. Traditional approaches have seen them more as collections of architecture than as social spaces despite the observation that, in the historical period at least, the city was essentially a community of citizens (Owens 1991, 1. cf. Rider 1916; Wycherley 1949; Graham 1962; McEnroe 1982). During the past three decades, the ascendancy of intensive field survey in the Aegean has seen a shift in emphasis, with increasing attention devoted to the interactions of ancient urban systems with their surrounding landscapes (see e.g. de Polignac 1984; 1995; Osborne 1987; Davis and Cherry 1990; Rihill and Wilson 1991; Rich and Wallace-Hadrill 1991; Snodgrass 1991; Watrous and Blitzer 1999; Bevan 2002; Watrous et al. 2004). These developments have provided a long-needed contextualisation of central sites within their broader social and economic worlds, as well as challenging traditional archaeological preoccupations with cities, sanctuaries, villas, elites and other perceived trappings of civilisations within different periods. But these valuable broader perspectives need to be complemented by ongoing study of the internal organisation and dynamics of urban sites.

Within archaeology more generally, the ways in which people lived in and moved through past rural landscapes have recently become a major focus of investigation (e.g. Tilley 1994; Edmonds 1999; Bender and Winer 2001). It is notable that when these approaches and methodologies have been extended to the built environment of settlements, case studies from the (historical) Greek world have been prominent in representing the specific category of urban sites (e.g. Jameson 1990a; 1990b; Nevett 1994). In fact, the study of intra-urban space as a means of exploring social relations and identities in the ancient Greek world is now starting to burgeon (as indicated by Westgate et al. 2007); yet there is still far to go in realising the full potential of this resource.

The present volume is the product of a conference that took place at the Faculty of Classics, Cambridge, in May 2004. The papers range in period from the Bronze Age to the Hellenistic era, and in space from Italy to Beirut. The title of this volume thus incorporates two (only partially overlapping) meanings of Greek: the territory of the modern nation-state, and areas of the ancient world with cultural influences from the Aegean. The volume weaves through this large time-range of different societies and cultures, addressing different types of evidence and embracing a variety of spatial scales from the individual household to the broader cityscape (including its mortuary components). The uniting thread of the articles is that they analyse ancient urban centres from within, exploring some of the ways in which people lived in, perceived and modified their built environments. But equally, despite this common thread, the extended diachronic and spatial ranges encapsulated in the conference were intended not only to facilitate the exchange of ideas, but also to allow the diversity of ancient urban forms to be recognised.

Any book about urbanism needs to begin with definitions. It is tempting to adopt a know it when you see it approach, but this is to assume that all ancient urban configurations will coincide with modern European conceptions of what a town should look like. Appropriate criteria for identifying urban settlements have been debated for both the prehistoric and historic periods (e.g. for the former, Konsola 1986 and 1990; Polychronopoulou 1990; van Effenterre 1990; Schallin 1997; Bintliff 2002; and Whitelaw 2004, esp. 1613; and for the latter, Morris 1991; Snodgrass 1991; Morgan and Coulton 1997; Osborne 2005). The two criteria conventionally used to identify a site as urban in fact often coincide (Morgan 2003, 545). The first is unusually large site size. In the prehistoric period, geographical area conventionally provides the empirical base point for inter-site comparisons, with population estimates then extrapolated from this (the most detailed and culturally sensitive studies have been carried out by Whitelaw 2000; 2001; see also Renfrew 1972, 2501; Wagstaff and Cherry 1982, 13940; Branigan 2001, 458; Bevan 2002, 2446). For the historic period, calculations on the basis of geographical area, using archaeological data (e.g. Snodgrass 1977; Cherry and Sparkes 1982, 144; Whitelaw and Davis 1991, 278; Hansen 2006, 74), have been supplemented by population estimates drawn from textual sources (e.g. Hansen 1997). The second criterion for urbanism is specialized function, which is defined in terms of diversity of activities and the existence of centralised (administrative) authority within the centre. Both criteria are often linked with significant social hierarchy in the settlement, although evidence of hierarchy is not a criterion for urbanism by itself (see e.g. Morris 1991; 2006).

These criteria for urbanism are especially suitable for the Bronze Age and the Classical-Hellenistic periods; however, whether we look at site size or types of centralized authority, significant levels of variation are apparent both diachronically and synchronically. In terms of scale, Minoan palatial centres on Crete, which are usually characterised as urban by default, vary from c. 4ha at Neopalatial Gournia up to 6080ha at Neopalatial Knossos (Whitelaw 2001, 29 fig. 2.10); the size range for Mycenaean palatial sites on the mainland was much smaller (with the largest, Mycenae, at a maximum of c. 40ha Whitelaw ibid.). In the Classical and Hellenistic periods the range is broader, with sites such as Halieis, at c. 16ha, towards the lower end of the scale (Ault 2006) and Athens, whose fifth century walls enclosed c. 215ha, at the upper (Morris 2006, 423). In terms of the organisation of centralised authority there is again significant variation. Within the Bronze Age, as discussed below, the Mycenaean states are generally characterised as monarchic bureaucracies, but identifying the elite structures within the monumental palace and villa complexes of Minoan Crete is more contentious. Much later, the Classical period witnessed an eclectic range of tyrannic, oligarchic and democratic regimes based around polis (city-state) and

Next page