CIVILIZATIONS

OF ANCIENT IRAQ

CIVILIZATIONS

OF ANCIENT IRAQ

Benjamin R. Foster

Karen Polinger Foster

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS Princeton & Oxford

Frontispiece. Tablet of the Epic of Gilgamesh, Yale Babylonian Collection (see ).

Copyright 2009 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street,

Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6

Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

Second printing, and first paperback printing, 2011

Paperback ISBN 978-0-691-14997-4

The Library of Congress has cataloged the cloth edition of this book as follows

Foster, Benjamin R. (Benjamin Read)

Civilizations of ancient Iraq / Benjamin R. Foster,

Karen Polinger Foster.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-691-13722-3 (hardcover : alk. paper)

1. Civilization, Assyro-Babylonian. 2. AssyriaAntiquities.

3. BabyloniaAntiquities 4. BabyloniaSocial life and

customs. 5. IraqHistoryTo 634. I. Foster, Karen

Polinger, 1950. II. Title.

DS7.7.F67 2009

935dc22 2008048067

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

eISBN: 978-1-400-83287-3

R0

ILLUSTRATIONS

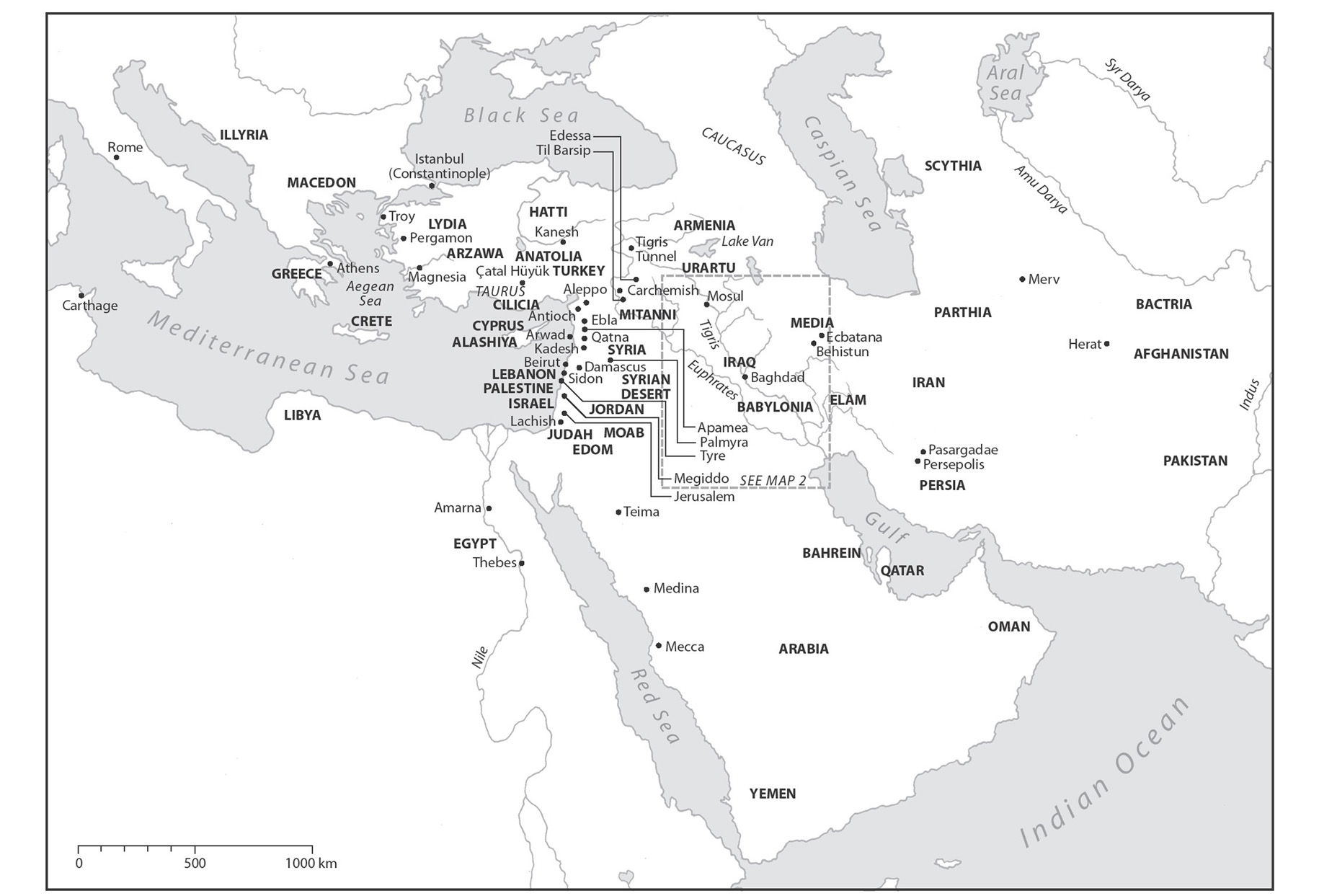

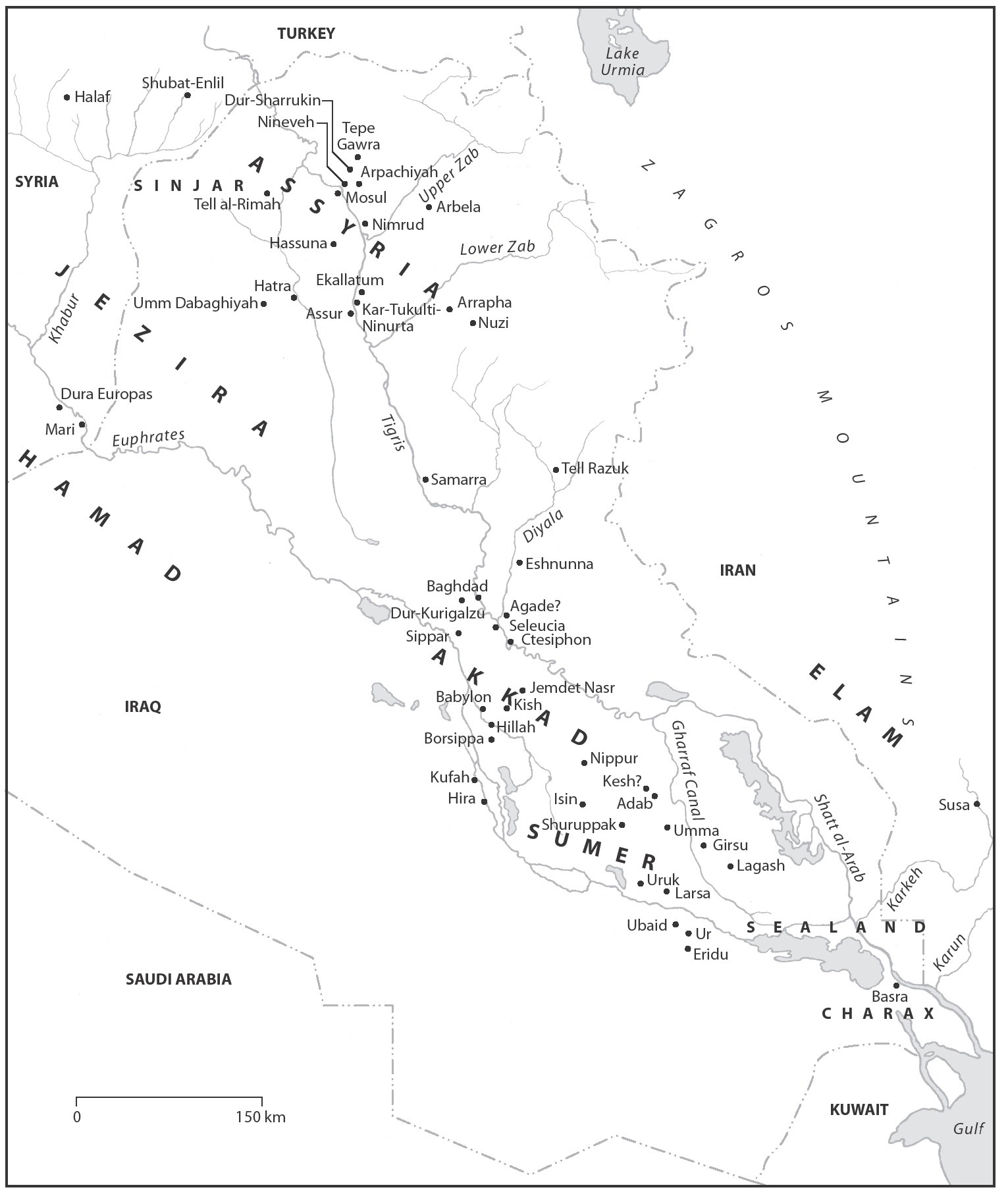

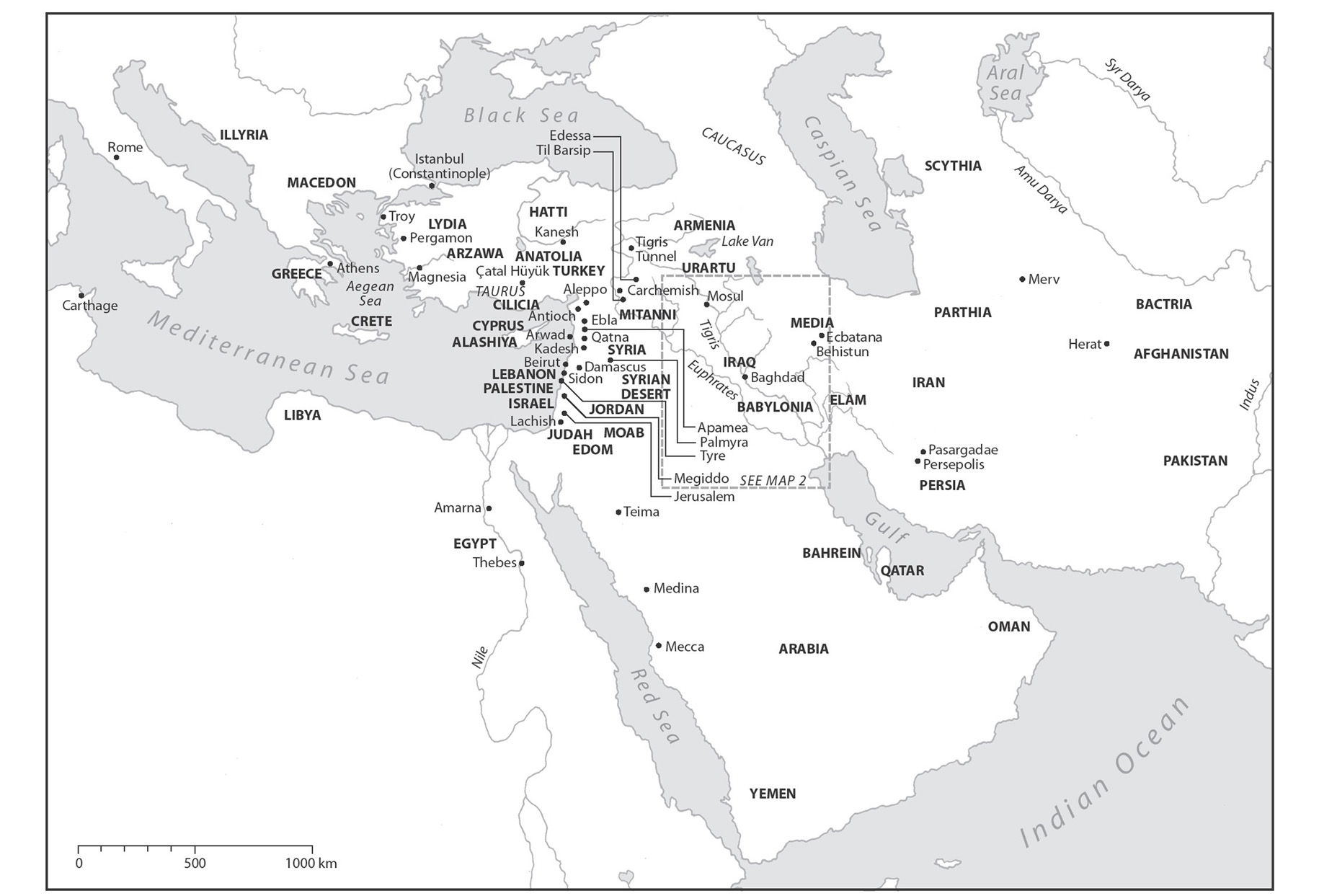

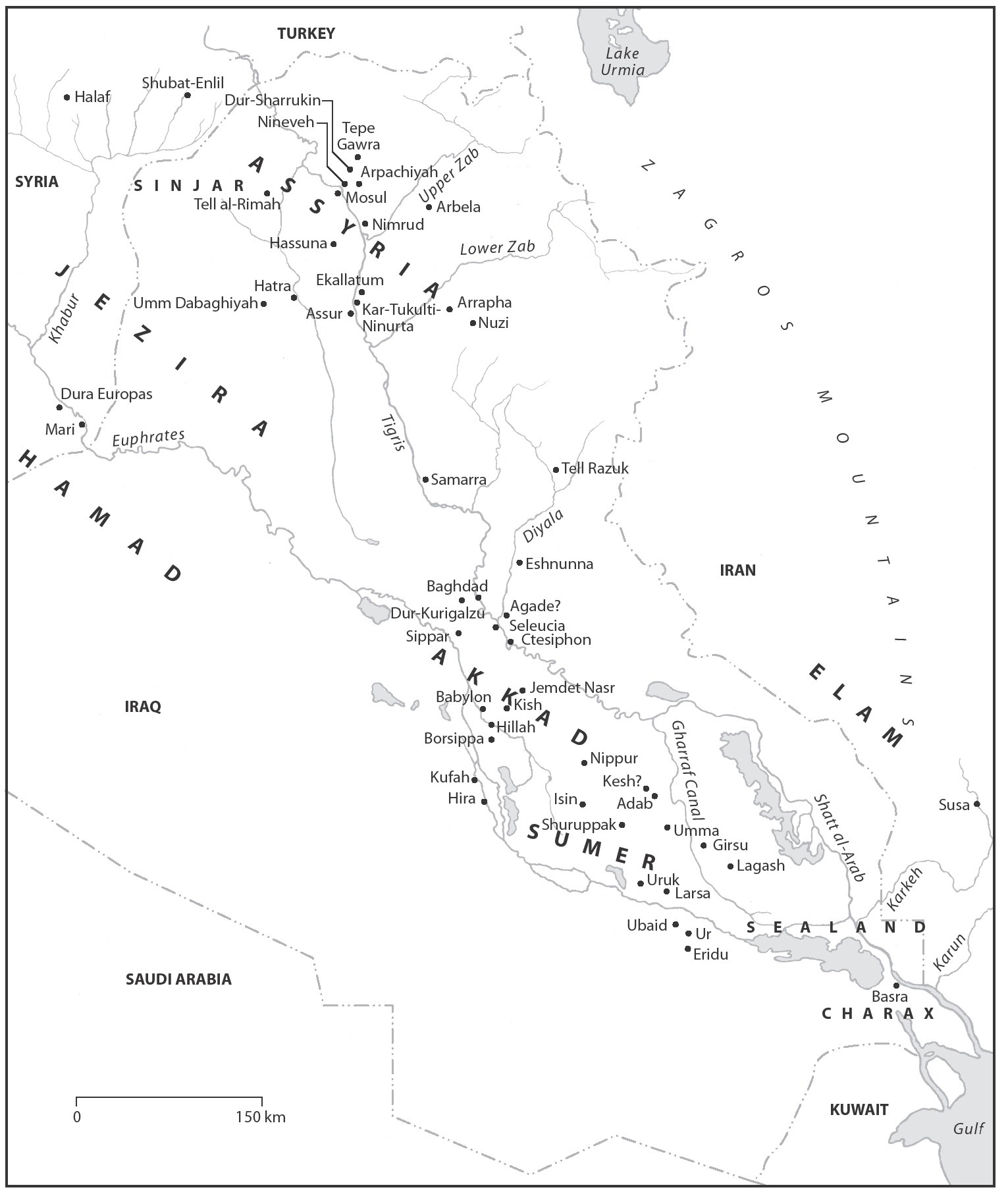

Maps

Figures

Frontispiece. Tablet of the Epic of Gilgamesh, Yale Babylonian Collection

PREFACE

Iraq is one of the birthplaces of human civilization. This land saw the first towns and cities, the first states and empires. Here writing was invented, and with it the worlds oldest poetry and prose and the beginnings of mathematics, astronomy, and law. Here too are found pioneering achievements in pyrotechnology, as well as important innovations in art and architecture. From Iraq comes rich documentation for nearly every aspect of human endeavor and activity millennia ago, from the administration of production, surplus, and the environment to religious belief and practice, even haute cuisine recipes and passionate love songs.

This book offers a brief historical and cultural survey of Iraq from earliest times to the Muslim conquest in 637, drawing together political, social, economic, artistic, and intellectual sources, both primary and secondary. The Epilogue offers an introduction to the history of archaeology in this region, set in the broader context of the development of archaeology as a scientific discipline. This section also focuses on the discovery, management, preservation, and destruction of the cultural heritage of Iraq.

The figures not only illustrate significant works of art and architecture in a representative choice of media and subjects, but also afford a basis for understanding cultural property issues in the aftermath of the looting of the Iraq Museum in April 2003 and in view of the ongoing devastation of Iraqi archaeological sites and trafficking in antiquities. The figure captions, taken as a whole, constitute a short essay on these matters, complementing the art-historical discussions in the text.

Some chapters are substantial revisions of work that initially appeared in Iraq Beyond the Headlines: History, Archaeology, and War, co-authored by both of us in 2005 with Patty Gerstenblith, whose publisher, World Scientific, permitted us to reshape the book into its present form.

Over the years, questions posed by students and audiences in our courses and public lectures have greatly contributed to the sharpening of our theses and our selection of material. Portions of the book originated in the McKee-May Academic Lectures in Greenwich, Connecticut, given by Benjamin R. Foster in the winter of 2003 at the invitation of Jennifer Vietor Evans.

The book has also much benefited from discussions with colleagues during several conferences and panels on current issues, among them A Future for Our Past: An International Symposium for Redefining the Concept of Cultural Heritage and Its Protection, held in Istanbul in June 2004; a series of programs entitled Iraq Beyond the Headlines, held at Yale University in April 2003, October 2003, October 2004, and February 2008; Iraq: At the Brink of Civil War? held at Yale University in April 2006; and The Future of the Global Past: An International Symposium on Cultural Property, Antiquities Issues, and Archaeological Ethics, held at Yale University in April 2007.

For references, images, information, thought-provoking comments, and eyewitness accounts, we are particularly grateful to Roger Atwood, Zainab Bahrani, Matthew Bogdanos, Annie Caubet, Dominique Charpin, Dominique Collon, John Darnell, Amira Edan, Joanne Farchakh, Bassam Frangieh, Patty Gerstenblith, Dimitri Gutas, McGuire Gibson, Nawala al-Mutawalli, Susanne Paulus, Gl Pulhan, John Russell, Catherine Sease, Alice Slotsky, Matthew Stolper, Margarete Van Ess, and Donny George Youkhana.

In the production of the illustrations and maps, we thank especially Yale Photographic Services, Peter W. Johnson, and those publishers still holding copyrights on the images reproduced here. Robert Tempio of the Princeton University Press has enthusiastically supported this project from the start.

CIVILIZATIONS

OF ANCIENT IRAQ

1. IN THE BEGINNING

Marduk created wild animals, the living

creatures of the open country.

He created and put in place Tigris and

Euphrates rivers,

He pronounced their names with favor.

Marduk, Creator of the World

Of Tigris and Euphrates

Ancient Iraq is the gift of two rivers. The Euphrates rises on the Anatolian plateau in Turkey, flows southwest into Syria and then turns southeast across Iraq, emptying into the Gulf. Its broad, shallow channel makes it an ideal source for irrigation water, and in many stretches the Euphrates is easily navigable. As the river moves across the southern alluvial plains and approaches the Gulf, it merges with the Tigris, amidst a network of smaller rivers, lakes, and marshes. To a Babylonian poet, the Euphrates seemed a mighty canal, divinely made:

O River, creator of all things,

When the great gods dug your bed,

They set well-being along your banks.

The Tigris, though it too rises on the Anatolian plateau, passes through more rugged terrain, at one point disappearing into a natural tunnel. A Sumerian poet mythologized the volcanic origin of the Tigris headlands as an epic battle between a hero-god and a personified, erupting volcano that gashed the earths body... bathed the sky in blood... and till today black cinders are in the fields. Both rivers flood when the snows melt in the highlands, but the Tigris often does so in violent, destructive onslaughts of water, swelled by its three main tributariesthe Upper and Lower Zab and the Diyalapouring down from deep gorges in the Zagros Mountains. By contrast, the two principal tributaries of the Euphratesthe Khabur and Balikh, which join it in northeastern Syriaenclose a swath of fine agricultural land known as the Jezira, whose productivity is augmented by sufficient annual rainfall for crops.