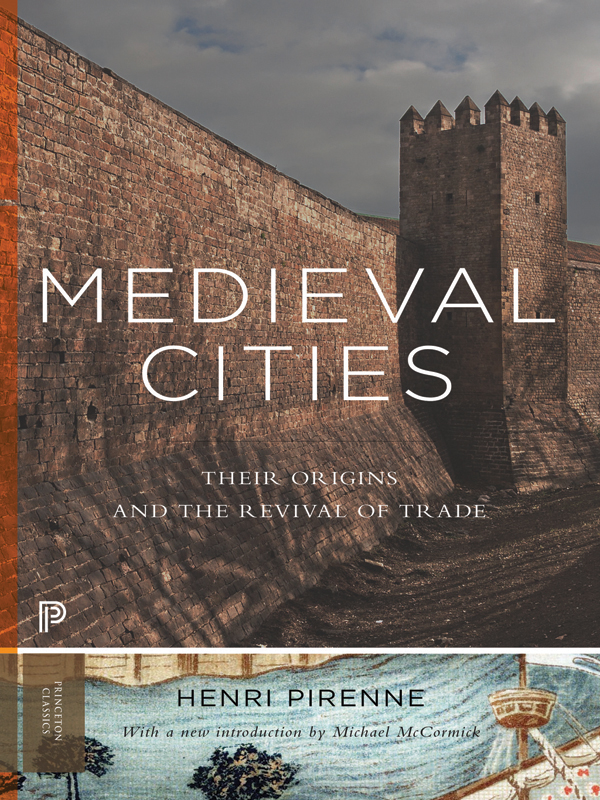

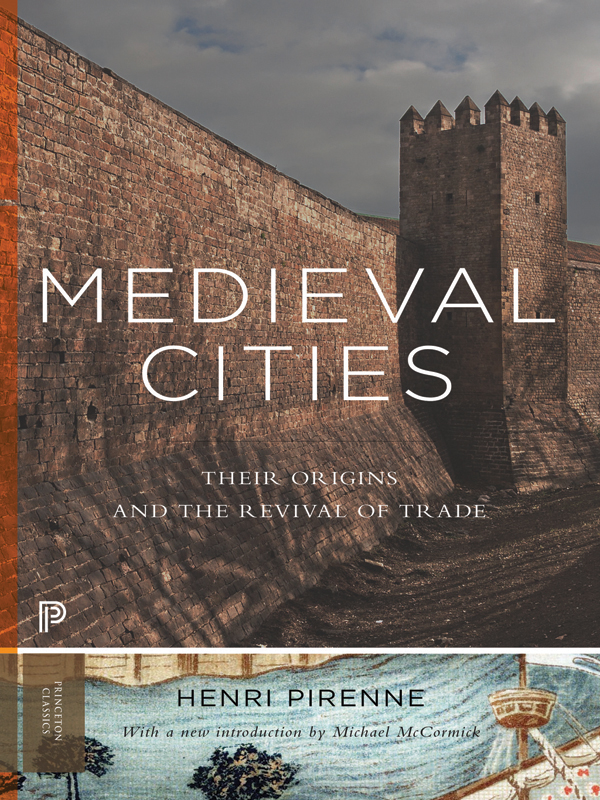

MEDIEVAL CITIES

MEDIEVAL CITIES

Their Origins and the Revival of Trade

HENRI PIRENNE

Translated from the French by Frank D. Halsey With a new introduction by Michael McCormick

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 1925, 1952 by Princeton University Press

Copyright renewed 1980 by Princeton University Press

Introduction copyright 2014 by Michael McCormick

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to Permissions, Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

Cover art: Top: Detail of Barcelona medieval walls. Bottom: Detail of Marco Polos departure. Both images courtesy of Thinkstock.

Design by Michael Boland for thebolanddesignco.com.

All Rights Reserved

First Princeton Paperback printing, 1969

First Princeton Classics edition, with an introduction by Michael McCormick, 2014

Library of Congress Control Number 2014934196

ISBN 978-0-691-16239-3

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Adobe Caslon Pro and Avenir LT Std

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

TO PRINCETON UNIVERSITY

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Globalization has a deep history. The Belgian historian Henri Pirenne (18621935), educated in Belgium, Germany, and France, cast in the twentieth century a long shadow over medieval studies and the history of the European economy. Medieval Cities, originally published in 1925, resulted from lectures that the celebrated medievalist and German war detainee gave in leading American universities on both coasts and in between (Keymeulen and Tollebeek 2011, 7684). These lectures were an early synthesis of Pirennes broad vision of the end of the ancient world, the rise of medieval Europe, and the origins and enduring impact of medieval cities in creating Europes economy and its distinctive civilization. Against the prevailing wisdom of his time, Pirenne argued that the Roman economy and the civilization built on it survived the Germanic invasions. Even if, politically, the former Roman provinces came under the leadership of barbarian kings, they remained on the Roman gold standard and integrated into the long-distance Mediterranean trade that Pirenne viewed as the dynamic driver of economic development. Pirenne argued that the ancient world really ended only when Islam violently shattered that Mediterraneans unified economic structures in the seventh and eighth centuries. With Charlemagne, Europe set out around 800 on a new path oriented toward the North Atlantic. Real cities as centers of economic development would emerge again only in the eleventh century when the human movers and shakers of the renewed growth of international trade coalesced in favored places and came to govern themselves. These medieval merchants new towns would shape a commercially oriented economy, some of whose essential patterns proliferated across the globe and, indeed, persisted down to the last century.

As Peter Brown, one of the twentieth centurys leading exponents of late antiquity, has observed, Pirennes argument that the ancient world outlasted the barbarian invasions, created the intellectual space in which the new field of late antique studies could bloom. And this is but one of the creative results of Pirennes remarkable oeuvre. His publications contributed to almost every aspect of the discipline. Beyond bold works of synthesis and countless learned articles, he established the model for bibliographical handbooks of Belgian history and published a palaeographical guide to reading medieval legal documents. Pirennes critical editions of Latin primary sources were exemplary for their time and range from a riveting eyewitness account of the crisis triggered by the murder of the Count of Flanders to volumes of Flemish textile industry records. His classroom teaching animated a school of disciples in Belgium and America, and the memorializing and debate about his life and work continue unabated (Duesberg 1938; Ganshof 1959; Lyon 1974, cf. E.A.R. Brown 1976; van Caenegem 1994; Simons 1997; Keymeulen 2011). His exquisite technical expertise served a distinguished historical imagination whose rigorous argument and limpid exposition illuminated the rise of Europes trading economy in the Middle Ages; the legal, social, and economic origins of medieval cities; the deep history of the principalities that would become the kingdom of Belgium; and the background of capitalism itself.

A child of the Industrial Revolution and champion in war and peace of the newly created nation-state of Belgium, Pirenne hailed from well-to-do manufacturers in the east of the small country. He studied at the University of Lige but learned perhaps his most fecund lessons in Germany, particularly from the teaching of the economic historian Gustav von Schmoller (18381917; see Thoen and Vanhaute 2011) and his friendship with a creative pioneer in medieval economic history, Karl Lamprecht (18561915; see Warland 2011). Most of his academic career unfolded as a professor and post-war rector at the university founded in the nineteenth century in the proud medieval city of Ghent. A member of the French-speaking population whose elite then dominated the new kingdom, Pirenne rose to national and international fame for his conduct and internment during the terrible ordeal of World War I. The conflict that raged back and forth across Flanders fields sharpened immense social and political stresses, particularly in Flanders, whose ancient and illustrious Germanic languageabout half way, linguistically, between English and Germanwas egregiously looked down upon by most of the dominant French-speaking elite, and whose native speakers then suffered considerable linguistic and political discrimination. Those political and social stresses, and the early successes of the Flemish Movement between the two world wars, are the context that led to Pirennes retirement from his position as professor of medieval history when his university became a Flemish-language institution in 1930. The man regarded as one of Europes foremost historians spent his last years in association with the Free University of Brussels, where his family has deposited his archives.

Pirennes posthumous reputation has taken somewhat different paths in North America and in his native Belgium. Although his work continues to be honored in both, Belgian historians have concentrated on the critical task of correcting the masters detailed work and on probing the ideological content of his syntheses, particularly the History of Belgium, with its rather unitary vision of the past, present, and future of the southern Low Countries (Keymeulen and Tollebeek 2011, 10811). Pirennes impact has been real but somewhat lighter in the German-speaking world. In his synthetic thinking about the end of the ancient economy and the origins of the European economy, Pirenne drew advantage from the work of the distinguished Austrian economic historian, Alfons Dopsch (18681953), whose major monographs argued powerfully for the continuity of the underlying Kultur of Western Europe through and beyond the great migrations. Though both might agree on the persistence of the Roman economy after the invasions of the fourth and fifth century, Pirenne came to a dramatically different view of the novelty and, indeed, impoverishment of the Carolingian economy thanks to what he believed was its divorce from Mediterranean trade. Whatever the merits of Dopschs optimistic reading of the Carolingian evidence, his systematic formulation of the questions and evidence reverberated to the end of the twentieth century in German-language scholarship more strongly than Pirennes vision. That is clear from the subjects and organization of the mighty six-volume study of the early medieval economy published by the Academy of Sciences at Gttingen (K. Dwel et al. 19851997).

Next page