Morgan - Medieval Persia 1040-1797

Here you can read online Morgan - Medieval Persia 1040-1797 full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: Array, year: 2016, publisher: Taylor & Francis Ltd;Routledge, genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

Medieval Persia 1040-1797: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Medieval Persia 1040-1797" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

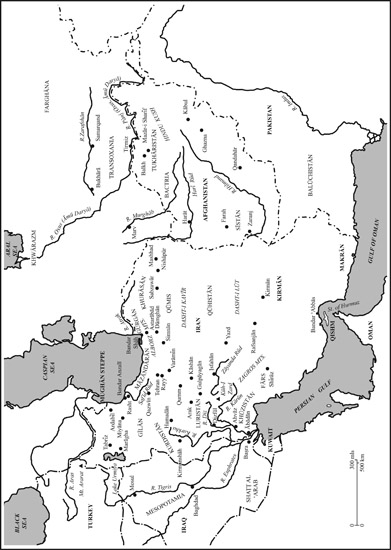

Medieval Persia 1040-1797 charts the remarkable history of Persia from its conquest by the Muslim Arabs in the seventh century AD to the modern period at the end of the eighteenth century, when the impact of the west became pervasive. David Morgan argues that understanding this complex period of Persias history is integral to understanding modern Iran and its significant role on the international scene.

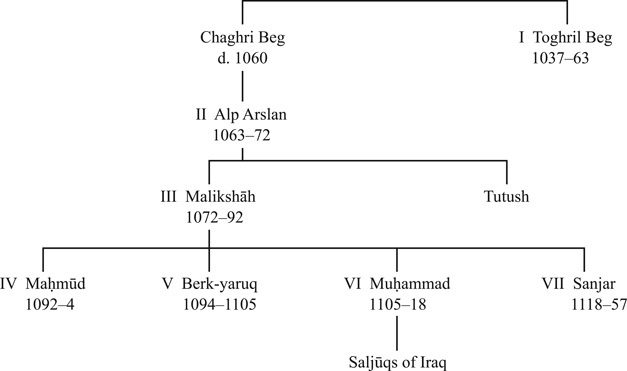

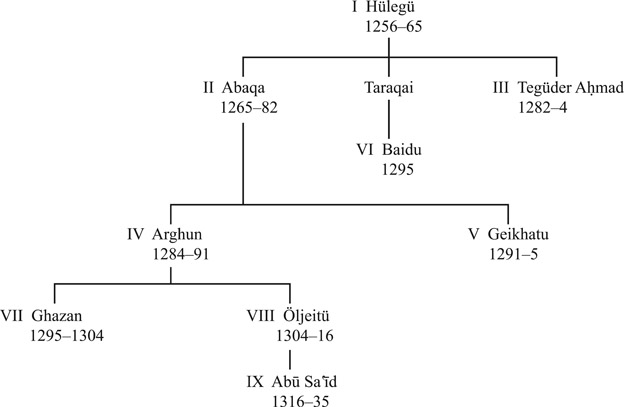

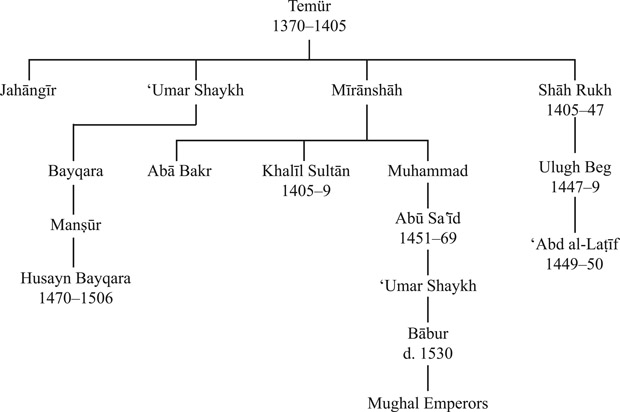

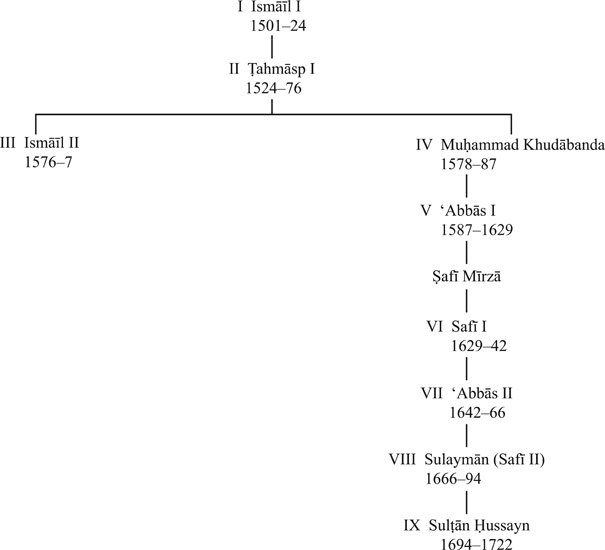

The book begins with a geographical introduction and briefly summarises Persian history during the early Islamic centuries to place the countrys Middle Ages in their historical context. It then charts the arrival of the Saljq Turks in the eleventh century and discusses in turn the major political powers of the period: Mongols, Timurids, Trkmen and Safawids. The chronological narrative enables students to identify change and consistencies under each ruling dynasty, while Persias rich social, cultural, religious and economic history is also woven throughout to present a complete picture of life in Medieval Persia. Despite the turbulent backdrop, which saw Persia ruled by a succession of groups who had seized power by military force, arts, painting, poetry, literature and architecture all flourished in the period.

This new edition contains a new epilogue which discusses the significant literature of the last 28 years to provide students with a comprehensive overview of the latest historiographical trends in Persian history. Concise and clear, this book is the perfect introduction for students of medieval Persia and the medieval Middle East.

Morgan: author's other books

Who wrote Medieval Persia 1040-1797? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.