I T IS ALMOST SEVENTY YEARS since publication of Richard Fitters seminal book on Londons Natural History in 1945. It was one of the earliest volumes (No. 3) in the New Naturalist series and one of the first attempts anywhere to investigate urban natural history in all its facets. His aim was to demonstrate the effects of human activities on nature, and the ways that nature responds, within a great city. He did it well. His book has remained authoritative and inspirational for generations of Londoners, scholars and naturalists ever since.

This is the first New Naturalist book to address the broad field of urban natural history since Fitters book. But it is very different. It tells two stories. The first deals with urban natural history from an ecological perspective, looking at a range of habitats and species that flourish in towns and cities and investigating the ecological processes involved. It is not intended to be a comprehensive account of urban natural history. Rather it traces the origins of the main types of habitat and their associated species and attempts to explain why particular conditions prevail. These are the ordinary habitats that we see every day, from railwaysides and cemeteries to parks and domestic gardens, as well as fragments of the wider world that have become caught up in the urban sprawl. Some species have been chosen to illustrate changes that occur through colonisation. Others were chosen because they are declining. These choices also reflect my personal interests and I make no apology for the strong emphasis on birds as they are the group that I know best.

The second story deals with the growth and development of urban nature conservation and the application of ecological knowledge to the design of new urban landscapes. Much has happened in the past thirty years and I have been fortunate to be closely involved throughout. I remember standing on Westminster Bridge in 1982 looking at London with new eyes having just been offered the job of Senior Ecologist with the Greater London Council. Little did I know that I was to be plunged into a maelstrom of activity as wildlife conservation spread into the cities and urban ecology suddenly became fashionable among academics. I witnessed many novel ideas becoming adopted as mainstream, including creation of the first ecological parks and early attempts to turn town parks into wildflower meadows. More radical when first proposed was the idea that we should value urban wastelands and use them as a model for habitat creation. Recently we have seen construction of major new nature reserves such as the London Wetland Centre and a proliferation of green roofs and other new habitats within the built environment as people look for sustainable solutions. New initiatives have been part of life.

I am writing this as I pass through Didcot on the train and catch a glimpse of a red kite quartering suburban gardens for food. What better symbol could there be? A bird brought back from the brink that is now recovering its place in towns and cities, to the great delight of residents. Its just one of the many stories.

A great deal has happened since 1982 and I hope that I have done justice to the enthusiasms and dedication of those involved. Which brings me to a third strand that runs all through the book. The story would not be complete without reference to the people who have made it all happen. The ecologists involved in unravelling the life histories of urban foxes, investigating bird populations of Londons squares or delving into the intricacies of ancient trees, provide the nuts and bolts of urban ecology. Then there are those involved in campaigns to protect important wildlife sites, the social scientists investigating the value of nature to people living in towns and cities, and landscape designers applying ecological knowledge and developing novel solutions for management of urban landscapes. They all have a story to tell. In a sense this book is a social history; a biography of a movement. Some of those involved have been particularly significant as visionaries. Max Nicholson, George Barker, Tony Bradshaw, Oliver Gilbert and Chris Baines stand out as leaders in a field that is full of dynamic individuals who have brought about changes in our relationship with urban nature. I have been fortunate to work with many of them.

It has been an extraordinarily rewarding period to be working as an urban ecologist and I am thankful for that. If this book helps to promote greater understanding and appreciation of the subject then it will have done its job.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This book would not have been possible without the help and encouragement of many people. Some provided guidance on places that they know well, others contributed on specialist topics, yet others helped with locating published material, to all of whom I am extremely grateful. I value the time spent with enthusiasts in various parts of Britain exploring the local natural history and I can only apologise in those cases where material has not been used owing to lack of space. The following is a list of people who have assisted and if there are others who I have inadvertently missed I beg your indulgence: John Archer, Simon Atkinson, Hilary Ash, Helen Baker, George Barker, Leo Batten, David Bevan, Catherine Bickmore, John Box, Lynda Brooks, Richard Bullock, Sara Carvalho, Rai Darke, Ed Drewitt, Mathew Frith, Niall Fuller, Meg Game, Jean Hansell, David Ingram, Lynda Lake, Mandy Leivers, Mike LeRoy, Grant Luscombe, Edward Mayer, Edward Milner, Dick Newell, Philip Oswald, Laura Palmer, Mike Poulton, William Purvis, Rob Randall, Peter Rock, Richard Scott, Peter Shirley, Chloe Smith, Matthew Thomas, and Ian Trueman. Thanks are also due to Wildlife Trusts, regional biological record centres and city ecologists in many places, especially Birmingham and the Black Country, Bristol, Edinburgh, London, Manchester and Sheffield. Thank you, too, for help from staff at Buglife, particularly Jamie Robins, Sarah Henshall and Steven Falk.

I am particularly grateful to people who have contributed photographs, especially Paul Wilkins; also Buglife, the Hawk and Owl Trust (Hamish Smith), the Parks Trust, Milton Keynes (Liz Woznicki), RSPB (Michael Szebor), Wildlife Trusts (Anna Guthrie) and the Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust (Catherine Beazley). Photo credits are included in the captions. Thanks are also due to Mike Wells and his staff at Biodiversity by Design in Bath who provided much debate and allowed me the freedom of their library. Special thanks too to those who commented on sections of the book in draft, especially Malcolm Rush whose comments were invaluable.

The book has been strongly influenced by the work of the London Ecology Unit. I am mindful of the tremendous wealth of material on urban ecology and nature conservation generated by members of the Unit over many years and would like to pay tribute to their endeavours. Thanks are due to all those whose work has found its way into the book.

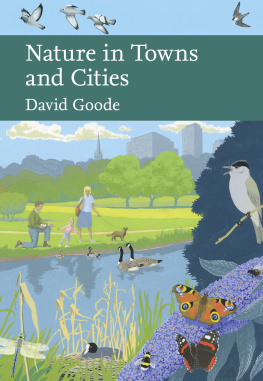

I would like to thank Jonathan Silvertown of the New Naturalist Editorial Board and Julia Koppitz at HarperCollins for their patience and encouragement and also Tom Cabot for his skilful design. To Robert Gillmor, my thanks for a lovely illustration for the jacket.

Finally I thank Johanna and Tom for their prolonged support and Helen for sharing the journey.

In memory of Diana

EDITORS

SARAH A. CORBET, S C D

DAVID STREETER, MBE, FIB IOL

JIM FLEGG, OBE, FIH ORT

P ROF . JONATHAN SILVERTOWN

P ROF . BRIAN SHORT

*

The aim of this series is to interest the general

reader in the wildlife of Britain by recapturing

the enquiring spirit of the old naturalists.