Cities by Design

For NAH

Copyright Fran Tonkiss 2013

The right of Fran Tonkiss to be identified as Author of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

First published in 2013 by Polity Press

Polity Press

65 Bridge Street

Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press

350 Main Street

Malden, MA 02148, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN: 978-0-7456-8029-3

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website: www.politybooks.com

Contents

Acknowledgements

My thinking about cities, space and issues of design has been deeply informed in recent years by the experience of working as a sociologist among architects, urban designers, planners and others in the London School of Economics Cities Programme. I would like to express my thanks to Juliet Davis, Suzanne Hall, Philipp Rode, Savvas Verdis and Ricky Burdett for their collegiality, support and generosity. At Polity, Emma Longstaff commissioned the manuscript and Jonathan Skerrett saw it through to publication, and Im grateful to both for their encouragement, patience and professionalism.

The discussion in Chapter 4 originated in an earlier essay, Informality and its discontents, in M. Anglil and R. Hehl (eds) Informalize! Essays on the Political Economy of Urban Form, Berlin: Ruby Press, 2012, 5570. Parts of the Afterword draw on Austerity urbanism and the makeshift city, City 17/3 (2013): 31224.

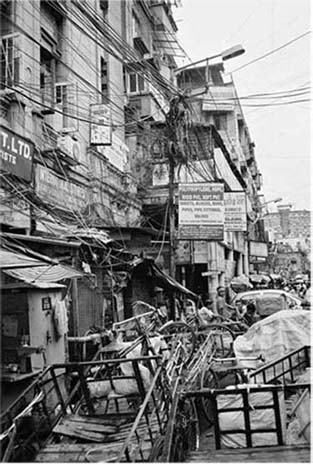

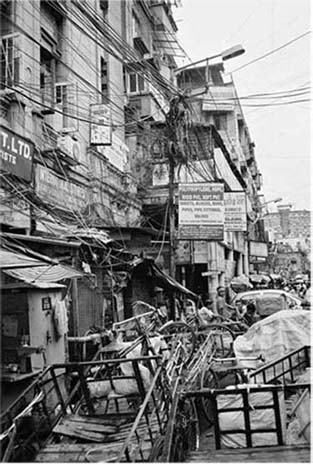

All photographs by Claire Mookerjee.

North Kolkata, 2010.

Introduction: Cities by Design

The architect, the planner, the sociologist, the economist, the philosopher or the politician cannot out of nothingness create new forms and relations. More precisely, the architect is no more a miracle-worker than the sociologist. Neither can create social relations .

(Lefebvre 1996 [1968]: 151)

City-making is a social process. This book examines the relationship between the social and physical shaping of cities, between how people use, create and live in space, and the material production of urban environments. It treats the design of cities as a social, economic and political problem not simply or primarily a technical or aesthetic challenge; and even less the specialist domain of any single expert as miracle-worker, as Henri Lefebvre so eloquently avers. Contemporary city design is a matter not only of iconic architecture, flagship projects or ambitious masterplans, but also of formal and informal practices that shape urban environments, produce and address urban problems, organize people as well as ordering space. If viable responses are to be developed to issues of environmental damage and energy use, economy inequality and social injustice, then cities will be crucial contexts for such solutions; but current processes of urbanization and practices of city-making too often intensify environmental problems and compound social and economic inequities.

With cities taking a majority and a growing share of the global population, and with rapidly increasing urban populations in developing contexts in particular, urban forms and urban experience are central to the study of human settlements and social arrangements. Focusing on the interplay between the social and the physical shaping of contemporary cities makes it possible to see how the material organization of urban space is crucial to the production and reproduction of social and economic arrangements, divisions and inequalities. The discussions that follow explore these issues in relation to critical aspects of contemporary urbanization: urban growth, density and sustainability; inequality, segregation and diversity; informality, urban environments and infrastructure. These are elements of urban form that mediate the physical and spatial with the social and economic. This is to define urban form in a multi-dimensional way, composed of material structures and physical spaces, but also and perhaps more fundamentally by social, economic, legal and political modes of organization and interaction. The design of cities emerges from the complex interaction of socio-economic with spatio-technical processes and practice. The forms in which cities take shape are deeply determined by economic arrangements, social relations and divisions, legal constructions and political systems; in turn, the material forms of cities provide the conditions in which key social and economic processes are produced.

Thinking about the design of cities in this extended way is relevant to cities in developed and developing economies. It would be a mistake to differentiate cities in high- and low-income contexts around a distinction between the planned and unplanned, or designed and organic urban forms even if such a distinction has been conventional in many accounts. The text focuses on processes and effects of urbanization in developed and developing cities, not so as to do away with the distinctions between them much less to suggest that their urban experiences are somehow equivalent but to explore how issues of population growth and decline, densification and sprawl, segregation and division, formality and informality, play out in different urban contexts and under very different socioeconomic conditions. This in part responds to the challenge of what Ananya Roy has called provincializing global urbanism, taking seriously the character and the contexts of urbanization in different settings without unthinking recourse to categories minted in or for the cities of the global north. But it also seems important to insist on points of commonality in the conceptual repertoire of urban analysis: to underline the fact, for instance, that informality is not a property of cities in developing economies, but a way of doing urban life pretty much everywhere; or that many poor- as well as rich-world cities are increasingly divided around the spatial secessions of affluent elites. It follows that my interest is in the connections between quite different and often distant cities between the consumption economies of rich-world cities, for example, and the environmental vulnerabilities of the urban poor as well as the marked divergences between them. This seeks to avoid the twin errors of subsuming various cities under a common logic of urban development, at one extreme, and, at the other, of over-stating the radical particularity of cities in ways that make broader urban theory and comparative analysis virtually pointless (see Beauregard 2010).