Copyright 2012 Thomas King

All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication, reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, or stored in a retrieval system without the prior written consent of the publisheror in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, license from the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agencyis an infringement of the copyright law.

Doubleday Canada and colophon are registered trademarks

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

King, Thomas, 1943

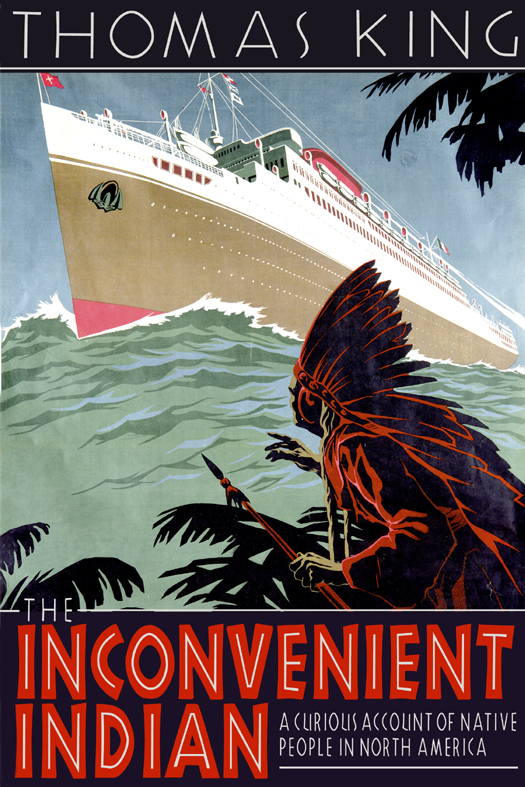

The inconvenient Indian : a curious account of Native People in North America / Thomas King.

eISBN: 978-0-385-67405-8

1. Indians of North AmericaHistory. 2. Indians of North AmericaSocial life and customs. 3. North AmericaEthnic relations. 4. Indians, Treatment ofNorth America. I. Title.

E77.K566 2012 970.00497 C2012-902445-7

Cover and text design: Andrew Roberts

Cover image: Poster advertising the Cosulich Line (colour litho), Italian School, (20th century) / Private Collection / The Bridgeman Art Library

Published in Canada by Doubleday Canada, a division of Random House of Canada Limited

Visit Random House of Canada Limiteds website: www.randomhouse.ca

v3.1

For the grandchildren I will not see.

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

WARM TOAST AND PORCUPINES

I am the Indian

And the burden

Lies yet with me.

Rita Joe, Poems of Rita Joe

ABOUT FIFTEEN YEARS BACK, a bunch of us got together to form a drum group. John Samosi, one of our lead singers, suggested we call ourselves The Pesky Redskins. Since we couldnt sing all that well, John argued, we needed a name that would make people smile and encourage them to overlook our musical deficiencies.

We eventually settled on the Waa-Chi-Waasa Singers, which was a more stately name. Sandy Benson came up with it, and as I remember, waa-chi-waasa is Ojibway for far away. Appropriate enough, since most of the boys who sit around the drum here in Guelph, Ontario, come from somewhere other than here. Johns from Saskatoon. Sandy calls Rama home. Harold Rice was raised on the coast of British Columbia. Mike Dukes home community is near London, Ontario. James Gordon is originally from Toronto. I hail from Californias central valley, while my son Benjamin was born in Lethbridge, Alberta, and was dragged around North America with his older brother and younger sister. I dont know where he considers home to be.

Anishinaabe, Mtis, Coastal Salish, Cree, Cherokee. We have nothing much in common. Were all Aboriginal and we have the drum. Thats about it.

I had forgotten about Pesky Redskins but it must have been kicking around in my brain because, when I went looking for a title for this book, something with a bit of irony to it, there it was.

Pesky Redskins: A Curious History of Indians in North America.

Problem was, no one else liked the title. Several people I trust told me that Pesky Redskins sounded too flip and, in the end, I had to agree. Native people havent been so much pesky as weve been inconvenient.

So I changed the title to The Inconvenient Indian: A Curious History of Native People in North America, at which point my partner, Helen Hoy, who teaches English at the University of Guelph, weighed in, cautioning that history might be too grand a word for what I was attempting. Benjamin, who is finishing a Ph.D. in History at Stanford, agreed with his mother and pointed out that if I was going to call the book a history, I would be obliged to pay attention to the demands of scholarship and work within an organized and clearly delineated chronology.

Now, its not that I think such things as chronologies are a bad idea, but Im somewhat attached to the Ezra Pound School of History. While not subscribing to his political beliefs, I do agree with Pound that We do NOT know the past in chronological sequence. It may be convenient to lay it out anesthetized on the table with dates pasted on here and there, but what we know we know by ripples and spirals eddying out from us and from our own time.

Theres nothing like a good quotation to help a body escape an onerous task.

So I tweaked the title one more time, swapped the word history for account, and settled on The Inconvenient Indian: A Curious Account of Native People in North America. Mind you, there is a great deal in The Inconvenient Indian that is history. Im just not the historian you had in mind. While it might not show immediately, I have a great deal of respect for the discipline of history. I studied history as part of my doctoral work in English and American Studies at the University of Utah. I even worked at the American West Center on that campus when Floyd ONeil and S. Lyman Tyler ran the show, and, over the years, Ive met and talked with other historians such as Brian Dippie, Richard White, Patricia Limerick, Jean OBrien, Vine Deloria, Jr., Francis Paul Prucha, David Edmunds, Olive Dickason, Jace Weaver, Donald Smith, Alvin Josephy, Ken Coates, and Arrel Morgan Gibson, and weve had some very stimulating conversations about history. And in consideration of those conversations and the respect that I have for history, Ive salted my narrative with those things we call facts, even though we should know by now that facts will not save us.

Truth be known, I prefer fiction. I dislike the way facts try to thrust themselves upon me. Id rather make up my own world. Fictions are less unruly than histories. The beginnings are more engaging, the characters more co-operative, the endings more in line with expectations of morality and justice. This is not to imply that fiction is exciting and that history is boring. Historical narratives can be as enchanting as a Stephen Leacock satire or as terrifying as a Stephen King thriller.

Still, for me at least, writing a novel is buttering warm toast, while writing a history is herding porcupines with your elbows.

As a result, although The Inconvenient Indian is fraught with history, the underlying narrative is a series of conversations and arguments that Ive been having with myself and others for most of my adult life, and if there is any methodology in my approach to the subject, it draws more on storytelling techniques than historiography. A good historian would have tried to keep biases under control. A good historian would have tried to keep personal anecdotes in check. A good historian would have provided footnotes.

I have not.

And, while Im making excuses, I suppose I should also apologize if my views cause anyone undue distress. But I hope we can agree that any discussion of Indians in North America is likely to conjure up a certain amount of rage. And sorrow. Along with moments of irony and humour.

When I was a kid, Indians were Indians. Sometimes Indians were Mohawks or Cherokees or Crees or Blackfoot or Tlingits or Seminoles. But mostly they were Indians. Columbus gets blamed for the term, but he wasnt being malicious. He was looking for India and thought he had found it. He was mistaken, of course, and as time went on, various folks and institutions tried to make the matter right. Indians became Amerindians and Aboriginals and Indigenous People and American Indians. Lately, Indians have become First Nations in Canada and Native Americans in the United States, but the fact of the matter is that there has never been a good collective noun because there never was a collective to begin with.