Contents

J. C. H. King

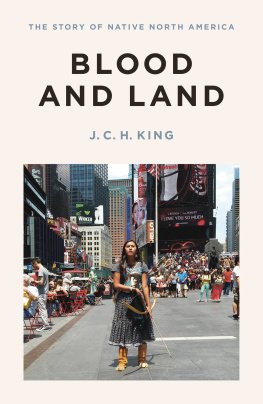

BLOOD AND LAND

The Story of Native North America

ALLEN LANE

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Allen Lane is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

First published 2016

Copyright J. C. H. King, 2016

The moral right of the author has been asserted

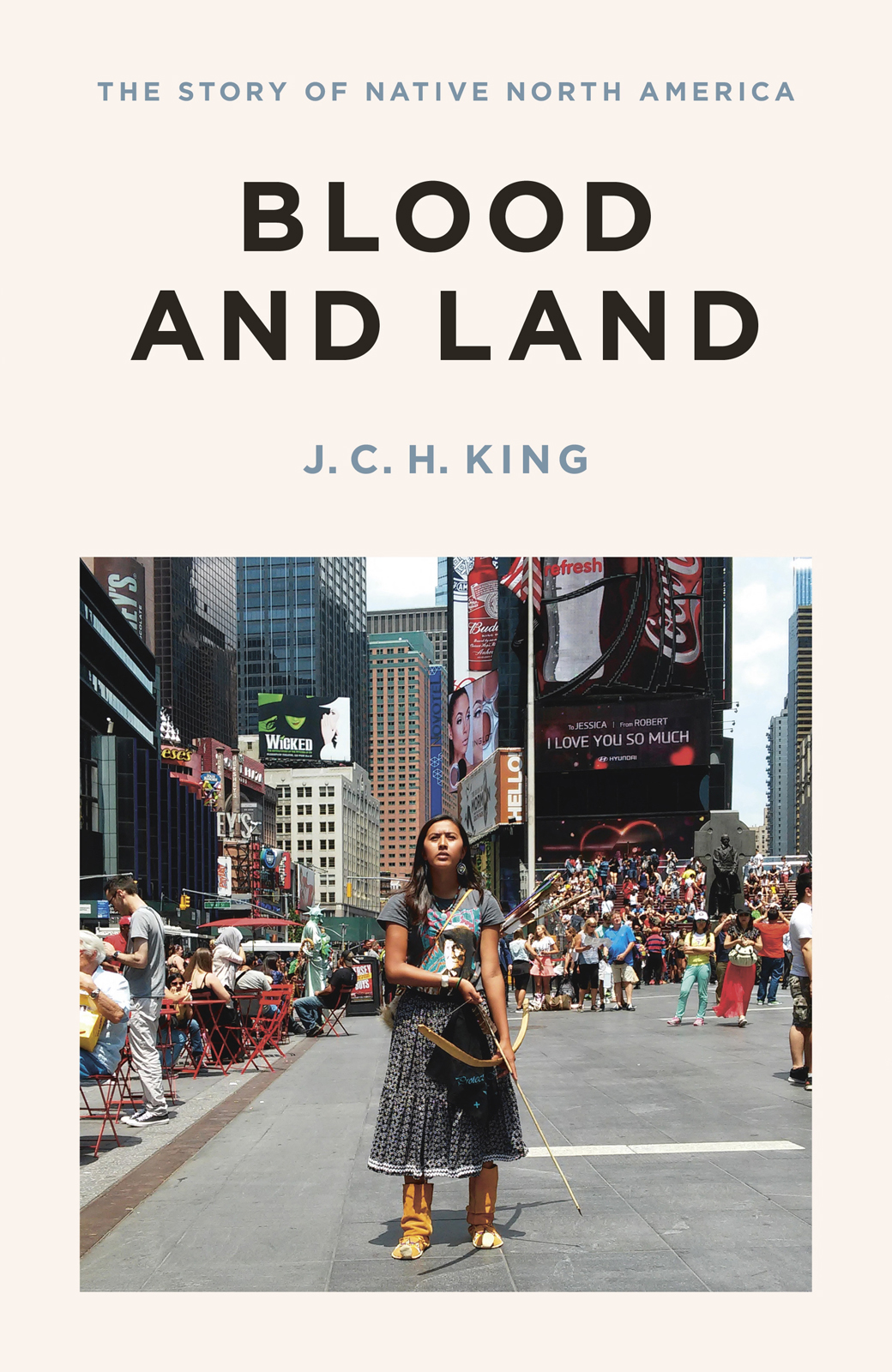

Cover: Naelyn Pike, Chiricauhua, marching in New York in July 2015, to protest against copper mining which will make the Oak Flat ceremonial campsite unusable to the San Carlos Apache, Arizona

Photograph Standingfox

Cover design: Tom Etherington

ISBN: 978-1-846-14808-8

THE BEGINNING

Let the conversation begin

Follow the Penguin Twitter.com@penguinUKbooks

Keep up-to-date with all our stories YouTube.com/penguinbooks

Pin Penguin Books to your Pinterest

Like Penguin Books on Facebook.com/penguinbooks

Listen to Penguin at SoundCloud.com/penguin-books

Find out more about the author and

discover more stories like this at Penguin.co.uk

A Note on the Text

Blood , respectively. It is often impossible to separate categories, such as ideas of land, religion and law, from each other, so many individuals and events appear in more than one chapter. What I hope this does is emphasize that history and culture are closely connected, and indeed, despite exceptional diversity, indivisible.

There are many names for the peoples described in this book. Native, indigenous, aboriginal, First Nation and Indian are all used below, and the terms mean different things to different people in different contexts. The Iroquois are today usually called Haudenosaunee, and the numerous peoples around and north of the Great Lakes may be referred collectively as the Ojibwe, the Chippewa or the Anishinaabe. My preference is to use different terms and names at different times, better usage of differing terms in appropriate contexts perhaps being preferable to absolute distinctions of right and wrong.

Preface

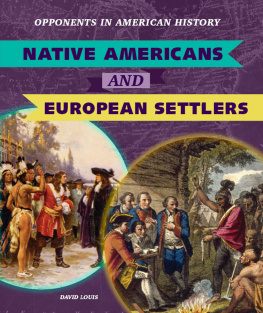

This book outlines Native American cultural history. This is intended to try to explain why, despite facing devastation and never-ending difficulties, Native America in contemporary Canada and the United States is successful. By successful I mean also that Native America thrives as a phenomenon in both the imagination and the intellect. The success is similar in kind, if not scale, to that of much greater entities in terms of population size and seemingly complexity such as the Classical or Judaeo-Christian worlds, or continents such as Asia and Africa. Of course, most of us in the West come, in one sense or another, from the Classical and Judaeo-Christian traditions, while we do not come from Native North America. Instead Native America provides a touchstone of identity: about who we westerners are and particularly who we are not.

Native North America has been especially successful also in surviving, in continually changing to meet the challenges of the dominant societies, from the influence of federal state and provincial authorities to the transgressive effects of popular culture. Little more than a century ago no one expected Native North Americans to do anything other than assimilate and die away. The major practical and symbolic moments in this process in the USA were the opening up of Indian Territory to white homesteading in 1898 and the conversion of this Native homeland into the state of Oklahoma (meaning red people in Choctaw) in 1907. At this point the Native population had reached a low point of around 375,000. Nobody expected Native America to recover, yet recovery occurred, in a series of cycles in which new institutional frameworks were set up, then altered, abandoned and improved, sometimes all three conflicting directions occurring simultaneously. And

In African America, well into the twentieth century, the racial rule ran: one drop and youre out: that is, one drop of African blood, a great-great-grandparent, say, and you were black. The rule now concerning Native North America is, with only slight exaggeration and mild irony, one drop and youre in. This came into play in the 2012 US Senate election, when the Democrat Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, now a senator, was challenged on her unproven claim to Cherokee status both by her Republican opponents and by Native Americans. Yet very many people are now aware of having Cherokee ancestry. Only perhaps two generations ago it would have been unthinkable in most cases for individual Americans actively to embrace their Native American genes. This is a remarkable and insufficiently marked change.

When I first visited Cherokee, North Carolina, and the Smoky Mountain community of Indian people, who avoided transportation west, it was a depressed, devastated hill town. In 1991, in the only downtown mini-mall, an elder was chiefing, that is, dressed in Plains Indian clothing with a feather war bonnet and posing for pay with the rather few tourists. Then I visited the factories where Cherokee made genuine New England quilts for Sears and tom-toms for football fans supporting the Atlanta Braves. Fifteen years later, when I returned to contribute to an exhibition about the Cherokee in Tulsa, the Cherokee had a vast casino, as well as their own police force and all other normal municipal services owned and controlled by them, thanks to their success in the gaming industry.

Yet perhaps the most remarkable aspect of Native North America is that a tiny population has contributed so much diversity to the worlds cultural landscape. If Native North America is considered alongside the Pacific, indigenous Middle and Andean America, South Asia, Africa or the Middle East, then perhaps something of Native North American exceptionalism becomes apparent. So what follows is, in this important sense, an account of Native American exceptionalism.

In academic studies, much is today made of the need to avoid reductionist description, in which differences are flattened out and identity stereotypes perpetuated, in order to develop more sophisticated ideas in which power and agency are returned to Native people. So emphasis is placed on concepts such as hybridity, contingency and agency, on the understanding of Native literature, film and art, on the development of cross-cultural, pan-Indian identities and the recovery of an understanding of the way both the USA and Canada grew out of reciprocal, but highly skewed, arrangements between Natives, Europeans and North Americans.

Scholarship cannot in the end entirely avoid locatedness: the specificity and the cultural geographies of the more than 1,000 Native nations in Canada and the USA. Actual origins and the development of identity are of fundamental importance, both in the distant past and in the cultural constructions from the nineteenth century onwards into the twenty-first. Frequently, however, the nuanced specifics of culture are reduced to archetypes, particularly in the media and museums. In the 1970s the museum-going public was either sceptical or uncritical and largely unaware of, and uninterested in, the cultural complexity of Native North America. Epithets such as red men, squaws, tomahawk chops and the expletive Ho! were still used. So the central role for the museum curator is to interpret and explain cultures through objects, and to place this understanding in a broader framework of deconstructed archetypes. That is, to reverse the process, the curator learns to take archetypes the Arctic hunter, the Plains warrior, the Environmental, Casino and Hollywood Indian and uses objects to explain how these simplistic formulations simultaneously communicate with yet limit and misinform the museum visitor.