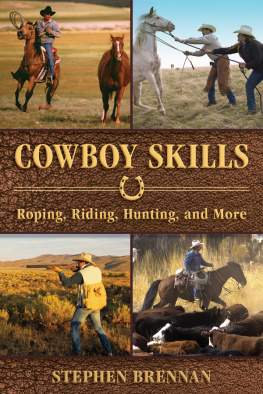

Copyright 2016 by Stephen Brennan

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

Cover design by Tom Lau

Cover photos: iStockphoto

Print ISBN: 978-1-63220-717-3

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-63220-865-1

Printed in China

For Finn

TABLE OF CONTENTS

NOTE

W e err when we regard survival skills purely in terms of the response to an immediate extreme danger or situationan enemy lurking behind the tree over there, a grizzly surprised at play with her young, a freak late summer blizzard, or famine when the buffalo do not come. Properly understood, survival skills also embrace the means by which whole cultures developed and endured.

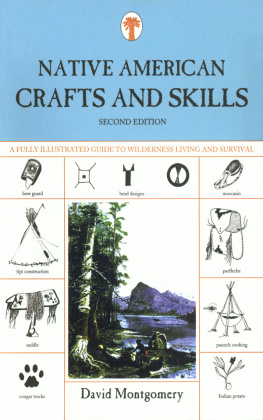

Our survey of the survival skills of the Native Americans is by no means exhaustive, which would be impossible. At the time of the European Contact its estimated that there were something like twelve hundred distinct peoples inhabiting the Americas, each with its own language, customs, material culture, and other imperatives associated with climatic and other challenges of each particular region.

Therefore we have limited our scope to the peoples of North America, and we have largelyexcept in the case of the horseconfined our survey to Native American ways and culture before Contact. Our strategy has been to sample the challenges, cultures, and techniques of specific peoples, and to allow them to stand in for and to illustrate survival skills of Native Americans generally.

This book employs the various terms Native Americans, Indians, and First Peoples interchangeablywith respect and without prejudicerecognizing that people most often associate and identify themselves with a specific local, familial, or cultural group; so whenever possible weve identified the artifacts, customs, and skills in our sampling with particular regional and tribal peoples.

CHAPTER ONE: TOOL KITS

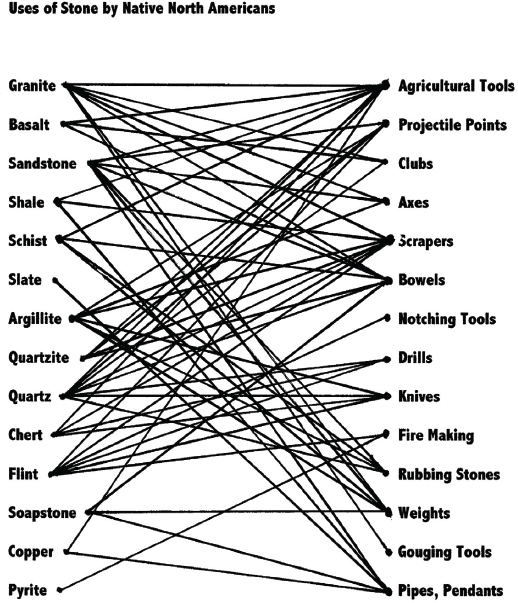

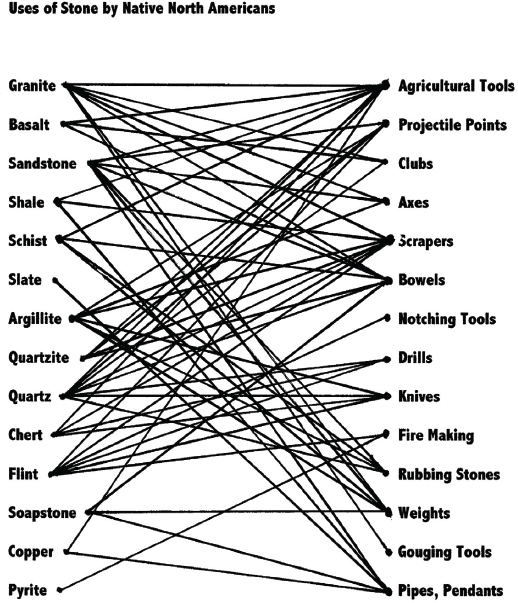

F or the thousands of years before Contact, the Native American peoples employed a lithic , or stone-age tool kit, comprised of stone, wood, shell, horn, bone, and plant and animal fiber.

But stone was the key, the one resource whose use made not only all the myriad things of daily life but also the tools from which other materials might be shaped and fashioned. This shaping process, the means by which stone was made to assume artificial forms adapted to human needs, was varied and ingenious, and its mastery was a matter of the greatest importance to Native American peoples.

SHAPING STONE

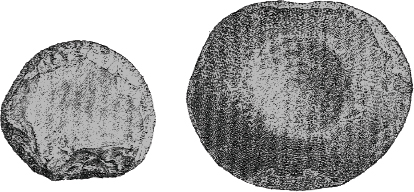

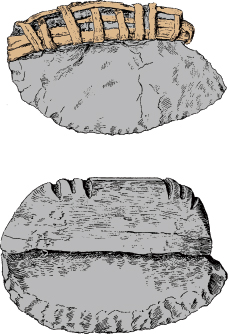

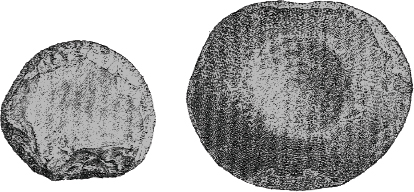

T he primary tool was the hammerstone. This might be of any size or weightdepending on the task to be undertakenbut it needed to be hard, relatively smooth, and able to be held in the hand. Quartzite makes a fine hammerstone because of its density and because it cannot be easily split. Water-worn stones, found by the sea or lakeshores and in stream beds, provided convenient tools for breaking, driving, grinding, and cracking.

Hammerstones

Simple tools did not need to be elaborate, and they could be made at once with a few blows of the hammerstone; many hammers, axes, knives, picks, scrapers, and the like were made with ease. But the more highly specialized implements, tools, and weapons required considerable time and effort.

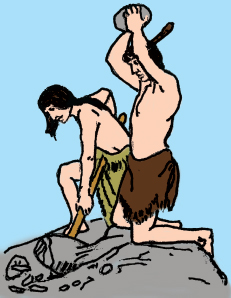

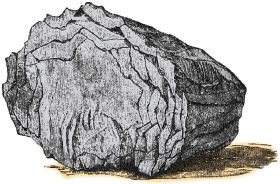

The first step was to locate the proper stone (or to trade for it) and then rough out the material from which the implements were to be fashioned. This involved fracturing the stone into the blanks , which were to be worked. This initial process was done with a hammerstone of one size or another. If the core was large, a large hammerstone might be wielded in two hands, or it might even be thrown.

PERCUSSION AND PRESSURE FRACTURING

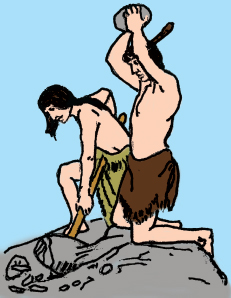

O nce the craftsman had assembled several likely blanks, he continued to work the stone using a combination of percussion and pressure fracturing techniques until he had fashioned the desired blade or implement.

A percussion fracture is accomplished by striking the blank a glancing blow with a hammerstone held in the hand, or by means of stick, a hafted stone, or an antler.

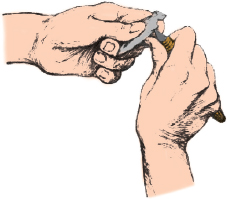

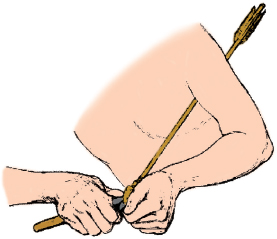

Pressure fracturing is the technique by which the arrow-point, blade, or other implement is completed, and involves the application of pressure to the edge of the stone being worked.

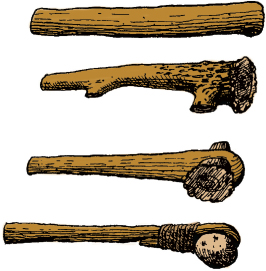

Most often an antler was the tool of choice. The craftsman might hold the stone in his hand, or he might work it on a stone or wooden anvil.

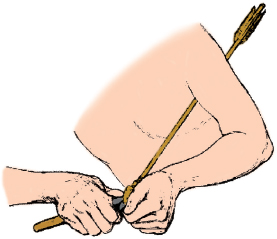

ARROW REPAIR

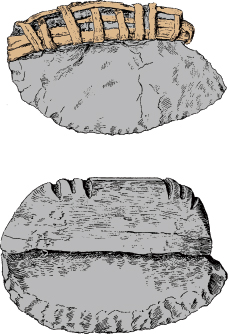

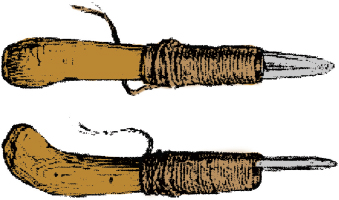

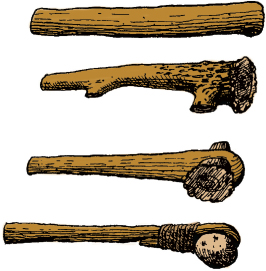

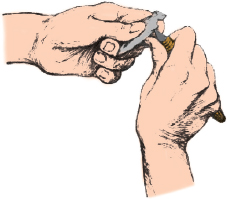

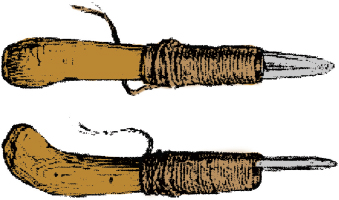

O n the war path or hunt, the warrior might find it necessary to repair his arrow, in which case this repair tool of wood and antler would come in handy to both sharpen and straighten his arrow.

PECKING

A nother technique for working stone is known as pecking or crumbling . The action is percussive and results in the crumbling of minute portions of the surface of the stone, which disappear as dust. Besides striking implements such as axes, clubs, and hammers, pecking was also used in the shaping of the stone mortar and pestle, stone pots, figurines, and other stone images. Pecking was also commonly used in finishing arrowheads and other bladed tools, as well as for close work like shaping stone drill bits.