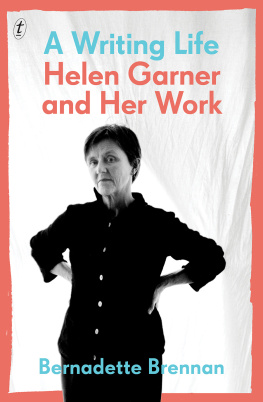

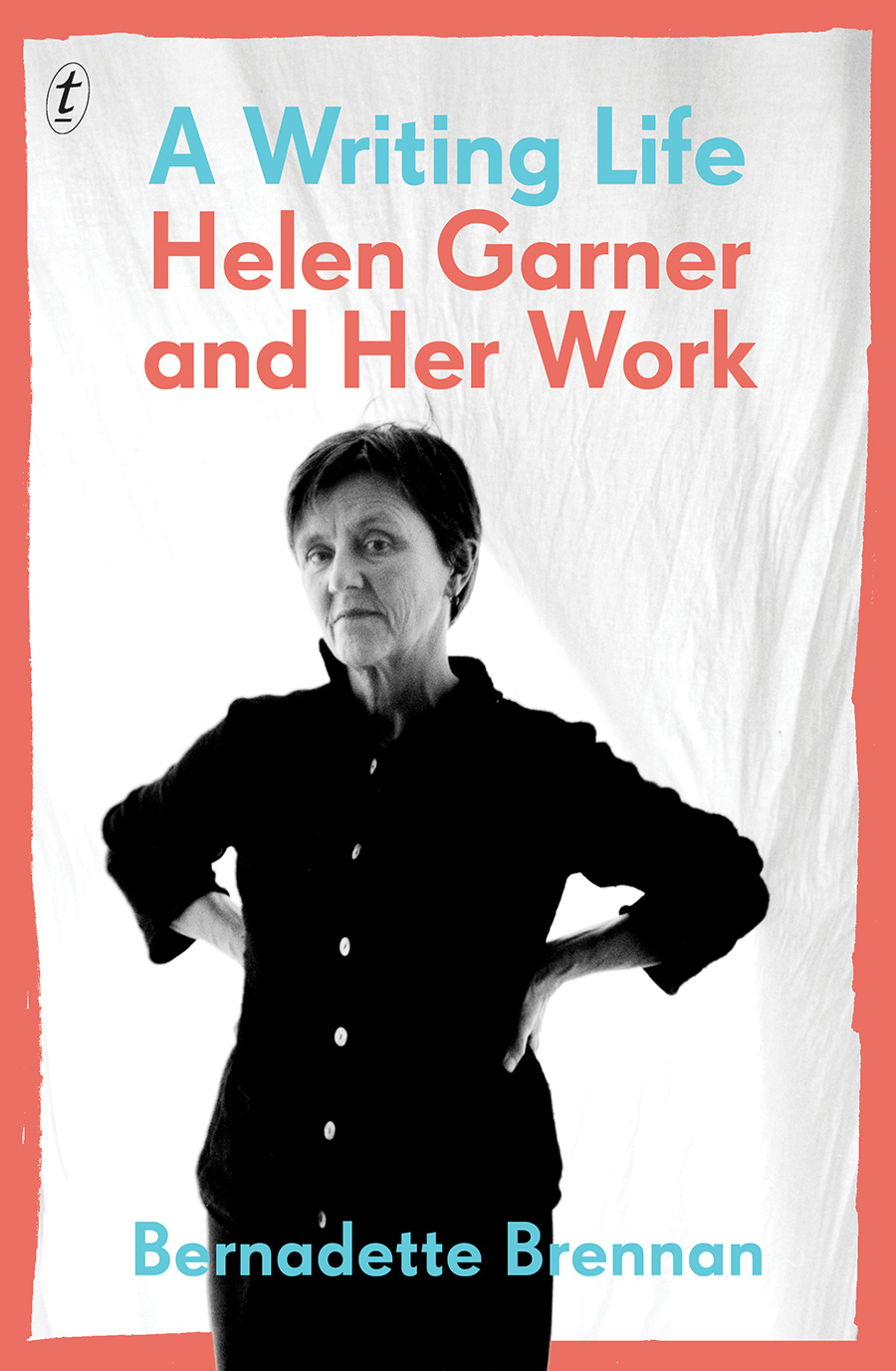

Dr Bernadette Brennan is an academic and researcher in contemporary Australian writing, literature and ethics. She is the author of a number of publications, including a monograph on Brian Castro, and editor of two collections: Just Words? Australian Authors Writing for Justice (UQP 2008), and Ethical Investigations: Essays on Australian Literature and Poetics by Noel Rowe (Vagabond 2008). She lives in Sydney.

textpublishing.com.au

The Text Publishing Company

Swann House

22 William Street

Melbourne Victoria 3000

Australia

Copyright 2017 Bernadette Brennan

The moral right of Bernadette Brennan to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright above, no part of this publication shall be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

First published in 2017 by The Text Publishing Company

Book design by Imogen Stubbs

Cover photograph Julian Kingma

Typeset by J&M Typesetting

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry

Creator: Brennan, Bernadette, author.

Title: A writing life : Helen Garner and her work/by Bernadette Brennan.

ISBN: 9781925498035 (paperback)

ISBN: 9781925410396 (ebook)

Subjects: Garner, Helen, 1942

Garner, Helen, 1942Correspondence.

Women authors, Australian20th century.

Australian literatureWomen authorsHistory and criticism.

Australian literature20th centuryHistory and criticism.

Tell me what the artist is, and I will tell you of what he has been conscious. Thereby I shall express to you at once his boundless freedom and his moral reference.

Henry James, preface to The Portrait of a Lady (1881)

, its one book. The book of what I make of the world and my life as I have lived it.

HELEN GARNER, IN CONVERSATION WITH JENNIFER BYRNE (2013)

Helen Garner began to fidget. She glanced at the moderator, Michael Cathcart, then at the American writer David Shields. The 2012 NonfictioNOW Conference had brought Garner, Shields, Margo Jefferson and Jos Dalisay together on a panel. The catalyst for Garners agitation was Shields assertion that almost no reality in our actual lives, we crave the real. In reply Garner said that, living next door to her three young grandchildren, she did experience real things. She thought there was nothing more real than the company of children and seeing how they understood the world. It seems to me, she said, there is a world and there is a reality.

Throughout her work, Garner has explored the reality of the world around her: the fraught complexity of relationships, the social experiments of communal living, the balance between personal freedom and moral responsibility, the rule of law and, always, questions about sex and power. Significantly, she has also ventured into aspects of the real that by their nature defy easy elucidation: spirituality and death.

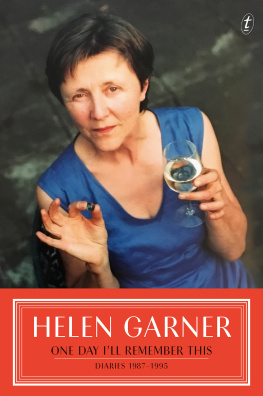

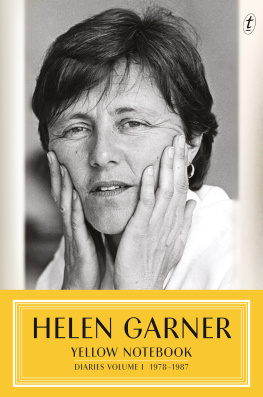

Thirty years ago Garner told Jennifer Ellison that she would never be so famous as to be recognised when she walked into a room. Now, aged seventy-four, and author of thirteen books, two screenplays, and a multitude of articles, essays and reviews, Garner is one of the best-known and, some would say, best-loved writers in Australia. That admiration is inspired by a sense that she is honest, authentic and familiar to readers. She appears to write so much of herself into her nonfiction, and many of her own experiences inform her fiction. Garner admits to striking up conversations with strangers on public transport, hungry for their tales of experience. Who can forget the poignant moment in her essay on the outpouring of grief over Jill Meaghers violent rape and murder, where she both weeps and laughs with an emotional father over the photo of his newborn daughter: ! Thank you for listening!

And yet, Garners work continues to polarise opinion. Some readers maintain the rage against what they perceive to be her ill-informed betrayal of feminism in The First Stone. Others rail against the ways in which she cannot but insert herself into textual dramas of pain and loss. Where some readers find and applaud her candour, others see a kind of ruthless egotism. Some critics remain exasperated by her refusal to stay within delineated genres. Monkey Grip and The Spare Room, they insist, are not novels. The First Stone, they argue, is fiction.

Garner has always been a boundary-crosser. Refusing the constraints of literary genre, she has sought to write across and craft her own versions of them. She admits to a me character in all her work. That character is a carefully constructed self. In her fiction, she unsettles her readers assumptions about protagonists by creating Helen characters, most blatantly in Little Helens Sunday Afternoon, Habe Dank and The Spare Room. In so doing, she demonstrates the complexity of a constructed fictional self. The I in her journalism and nonfiction is, as Janet Malcolm has argued about her own work, , a functionary connected tenuously to the actual writer. When she came to write Joe Cinques Consolation, for example, Garner toyed with creating a third-person HG with access to the thoughts and memories of a first-person HG. In her journal she asked: Cd I create a 3rd person I? A m/aged writer HG? With sore feet & hair anxieties, the loneliness, & life experience & ability to get an imaginative grip on the Cinques loss.

In May 1985 Garner wrote a column for the Australian Womens Weekly in which she recounted the belittling response given by Doris Lessing to a reader who asked if Lessings work was autobiographical. The question, wrote Garner, issueand critical issue, for that matterisnt that a writer will write about some of what has happened to him, but how he writes about it, which, when understood properly, takes us a long way to understanding why he writes about it.

So how best to approach the how and the why of Garners books, screenplays and essays? Given her experimentation with form, genre, voice and style, this study also crosses established critical boundaries. It can be neither a conventional biography nor a strict monograph. Garners life and writing inform and shape each other to such a degree that it is not possible to understand one without the other. With a respectful nod to Janet Malcolm, this book is a literary portrait of Garner and her work. In her essay Forty-One False Starts, Malcolm constructs a portrait of the American artist David Salle. Through fragmentary entries, she traverses aspects of Salles life, his art, published reviews and her interviews with him, adding a touch here, modifying something there. She has a profound respect for the absences, for what cannot be known, or need not be known. The essay is a portrait of a complex artist that acknowledges the impossibility of capturing the full essence of another human life.

. She is as spare and as honest as her work. Garner remembers feeling very relaxed in Sages presence. She was impressed that Sages never tried to make her smile. When she later sat for Sages in her Double Bay studio, the foundations of a respectful friendship were laid. Sages made thirty-seven charcoal drawings in preparation for her portrait. Garner enjoyed watching each emerge.

Sages True StoriesHelen Garner was completed in 2003. It now hangs in the National Portrait Gallery in Canberra. The portrait captures, through its combination of gesture and expression, many of Garners seemingly contradictory traits: she is somewhat relaxed yet displays her characteristic anxious poseher right hand raised to her temple. Her gaze is direct and almost too vividly open, suggesting that she is both surprised and a touch unimpressed, even resistant, to the whole project of portrayal. The lips are thin, not exactly pursed but firmly closed. It is a portrait of an alert, inquisitive, unglamorous woman who is at once strong and vulnerable.