SHORT BLACKSare gems of recent Australian writing brisk reads that quicken the pulse and stimulate the mind.

SHORT BLACKS

1 Richard Flanagan The Australian Disease:

On the decline of love and the rise of non-freedom

2 Karen Hitchcock Fat City

3 Noel Pearson The War of the Worlds

4 Helen Garner Regions of Thick-Ribbed Ice

5 John Birmingham

The Brave Ones: East Timor, 1999

6 Anna Krien Booze Territory

7 David Malouf The One Day

8 Simon Leys Prosper: A voyage at sea

9 Robert Manne

Julian Assange: The cypherpunk revolutionary

10 Les Murray Killing the Black Dog

11 Robyn Davidson No Fixed Address

12 Galarrwuy Yunupingu

Tradition, Truth and Tomorrow

Published by Black Inc.,

an imprint of Schwartz Publishing Pty Ltd

3739 Langridge Street

Collingwood VIC 3066 Australia

www.blackincbooks.com

Copyright Helen Garner 2001

Helen Garner asserts her right to be known as the author of this work.

First published in The Feel of Steel, Picador, 2001.

This edition published 2015.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior consent of the publishers.

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry : Garner, Helen, 1942 author. Regions of thick-ribbed ice / Helen Garner. 9781863957663 (paperback) 9781925203509 (ebook) Short blacks ; no.4. Professor Molchanov (ship) Voyages and travels.

AntarcticaAnecdotes.

919.8904

Cover and text design by Peter Long.

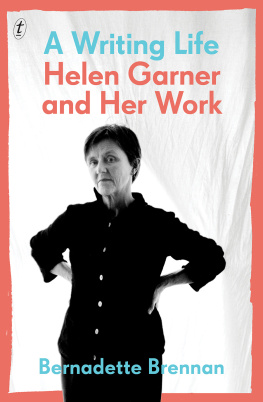

HELEN GARNER has written novels, short stories, screenplays and many acclaimed works of journalism. She was the recipient of the 2006 Melbourne Prize for Literature. Her books include Monkey Grip, The Childrens Bach, Joe Cinques Consolation, The Spare Room and This House of Grief.

T hey say that tourist ships to Antarctica, even more than ordinary human conveyances, are loaded down with aching hearts. Deceived wives and widowers, men whove never been loved and dont know why, Russian crew forced to leave their children behind for years at a time, grown women whove just buried a beloved parent, people with cancer travelling to the cold before they die. They say people come here looking for solace. And then there are the married couples: how calm the old ones, how eager the new! but isnt a couple the greatest mystery of all?

*

The hats. Oh, theyre terrible. One woman broaches the deck pulling on a thing like a sponge-bag, made of purple polypropylene. A little old lady is wearing a grey wool bonnet straight out of a Brueghel painting. A young bloke in spectacles sports a cap of multi-coloured segments, topped with a twirl and several small silver bells.

My own headgear, a hideous borrowed job featuring red earmuffs and a peak, is still stuffed into a corner of my suitcase, down in cabin no. 521 which Im there to share with a perfect stranger called Robyn (and Ive forgotten my earplugs).

So far, an hour after weve disembarked from Ushuaia, an Argentine port in Tierra del Fuego, I am still stubbornly refusing to believe in the cold, though my fingers have shrunk so thin that my wedding ring keeps sliding off, and my eyes and nose are streaming. If you fall overboard, states the Lonely Planet Guide grimly, you will die. Im not the Antarctic type. Im hanging out for a short black. Im not adventurous, and Im too sad to be sociable with strangers.

Stop whingeing. As the late summer Saturday afternoon draws on, we chug down the Beagle Channel, a body of calm water that splits the bent nib of South America into Chile and Argentina. The channel lies along a row of harsh, impossibly sparkling-topped mountains, each with its diaphanous scarf of cloud. Our ship is the Professor Molchanov out of Murmansk in the former Soviet Union, where, they say, scores of ships lie at anchor, unused, unwanted, rusting the detritus of empire. Our crew is Russian; our captain, though only thirty-eight, is an ice-master.

I look young, he says, but I am old inside.

He is also, various women agree later in the bar, a dish.

Havent you taken a seasick pill yet, Helen? asks Terry, a vet from Brisbane. Take one. Take it now.

I obey. By 8 p.m. I am nodding off at the dinner table among my fellow adventurers, most of them shy, many of them older than I am. In the early hours of Sunday morning we turn out of the Channel and into the Drake Passage where, while everyone but the crew is sound asleep, we hit a force-seven gale which will rage unabated for two days and nights.

The pills knock out nausea, but the simplest tasks going to the lavatory, getting dressed become Herculean. Robyn and I lurch past each other in the cramped space of our cabin, flung against walls and cannoning off cupboard fronts. Somehow a lifeboat drill is achieved, after which we hibernate. Our porthole is bisected by a madly tilting grey line. I am in love with my bunk, so narrow and perfect, like the single bed of childhood.

Sometimes Ann, the Molchanov doctor, materialises next to my drugged head, holding out a bottle of lemon-flavoured water, a handful of dry biscuits. Morning and evening a quiet voice comes over the tannoy into the cabin: this is Greg Mortimer, eminent mountaineer Everest, K2 and leader of our voyage. (No one calls it a tour or a trip, and since the storm began I have stopped seeing this as pretentious.) He has a knack of saying only whats required, without embellishment. To city people disturbed by the screaming wind, his voice is comforting. Sleep well, he says at night, like a comforting, benevolent father.

By Monday evening the huge waves smooth out. People creep from their burrows. Some have, incredibly, been unperturbed, attending learned disquisitions in the bar on the habits of penguins. Other voyagers confess to having spewed in public a great leveller. Thea, the woman in the Brueghel bonnet, shows off a carpet-burn the size of a dollar coin on her forehead. Everyone is friendlier since the storm: now we are shipmates.

Around 9 p.m. we gather on the bridge to keep vigil for our first iceberg. This far south, in February, it doesnt get dark til after eleven. The bridge is a serious place, of work and watching. The Russian officers are big blokes smelling of cigarettes, with moustaches and silver teeth, and voices that rumble from deep in their torsos. They murmur to each other, slip out on to the deck for a smoke, stand at the wheel or bend over charts spread on drawing boards. We are shy of them and keep stepping out of their way.

Out on deck the air is gaspingly cold but the evening sky is pretty, the water a steely, inky grey-blue. Suddenly theres a moon, riding tranquil between layers of bright cloud. Leaning over the rail I see my first tiny chunk of ice go bobbing past, very close to the ships side. At once Im seized by an urge to compare it with something with anything: its the size of a loosely flexed hand, palm up; like a Disney coronet with knobbed points; as hollow as a rotten tooth. For some reason I am irritated by this urge, and make an effort to control it.

Inside, the bridge is warm and dim. Thirty people stand about talking, but intent on the greying line that divides sea from sky. There it is theres one. And another. The first iceberg is only a pale blip on the horizon. The second is greyer, straighter-sided, more like a building. Night thickens as we approach them. Iceberg no.1 is unearthly, mother-of-pearl, glowing as if with its own inner light source. People grow quiet, their social chatter stills. The only sounds are the buzz and hum of the radar, the dull rumble of the engine, and out on deck the rushing of the wake.

Next page