SHORT BLACKS are gems of recent Australian writing brisk reads that quicken the pulse and stimulate the mind.

SHORT BLACKS

1 Richard Flanagan The Australian Disease: On the decline of love and the rise of non-freedom

2 Karen Hitchcock Fat City

3 Noel Pearson The War of the Worlds

4 Helen Garner Regions of Thick-Ribbed Ice

5 John Birmingham The Brave Ones: East Timor, 1999

6 Anna Krien Booze Territory

7 David Malouf The One Day

8 Simon Leys Prosper: A voyage at sea

9 Robert Manne Julian Assange: The cypherpunk revolutionary

10 Les Murray Killing the Black Dog

11 Robyn Davidson No Fixed Address

12 Galarrwuy Yunupingu Tradition, Truth and Tomorrow

Published by Black Inc.,

an imprint of Schwartz Publishing Pty Ltd

3739 Langridge Street

Collingwood VIC 3066 Australia

www.blackincbooks.com

Copyright David Malouf 2003

David Malouf asserts his right to be known as the author of this work.

First published in Best Australian Essays 2003, Black Inc., 2003.

This edition published 2015.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior consent of the publishers.

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry:

Malouf, David, 1934 author.

The one day : the memory of Anzac / David Malouf.

9781863957694 (paperback) 9781925203530 (ebook) Short blacks; no.7.

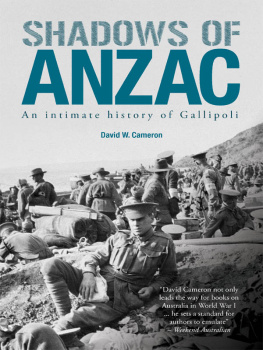

Anzac Day. World War, 19141918Participation, Australian

Anniversaries, etc. World War, 19141918CampaignsTurkey

Gallipoli PeninsulaAnniversaries, etc.

940.48194

Cover and text design by Peter Long.

DAVID MALOUF is the author of poems, fiction, libretti and essays. In 1996, his novel Remembering Babylon was awarded the first International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award. His 1998 Boyer Lectures were published as A Spirit of Play: The Making of Australian Consciousness. His most recent novel is Ransom.

I dont think anyone these days would deny that Anzac Day has established itself in the minds of Australians as the one day that we celebrate as a truly national occasion; a day, that is, when we look around and observe who we are; in the sense, first, of who is present, but also in the larger sense of what it is, in the way of experience, but also of shared attitudes and affections and loyalties and concerns, that brings us together as a single community, as a single people involved in a shared enterprise, whatever our individual differences and divisions.

I say the one day because our official National Day, 26 January, the anniversary of the first day of settlement, Australia Day, seems to me to have no general claim on our affection and to be seen by many of us as an occasion that is not fully inclusive and it never can be, of course, while for Indigenous Australians it is seen, and more importantly felt, as a day of conquest and dispossession. Australia Day has been declared our National Day. Imposed, officially, from above, and Australians on the whole are pretty resistant to choices they have not made for themselves. Anzac Day has been chosen. But things were not always like that. Part of the strength of that choice is that it has happened slowly, over time, and with many changes both in what the day represents and who has the right to define and manage it over time and through long and sometimes bitter argument.

How all that has happened, and why, is partly what I want to speak about tonight. What has changed? Is it us, or the day itself? What has Anzac Day come to mean that is different from what it meant, say, fifty years ago? And what does that tell us about the way we now see ourselves? The day has a history, and its history is in some ways our history over the past fifty years.

This present status of Anzac Day is astonishing to those of us who remember the way things were in the 50s. Back then, it was, officially, a holiday; that is, theatres were closed, so were the shops, but not, significantly, the pubs. And it was pretty well accepted that Anzac Day was a dying institution. The numbers that turned out for the Dawn Service were small and dwindling. Many of the men who had served in the two wars especially men who had served in the Second World War had become disaffected with the RSL, that is, the Returned Services League, the veterans association a lot of them no longer marched, and they had always, in a very Australian way, a good many of them, been non-joiners. The day had no appeal to young people, and for a good many of us in my generation it was a source of actual hostility.

The RSL, which claimed ownership of Anzac Day, and managed it, was one of several pressure groups that in those days were battling, pretty openly, to determine the way Australia might go in the early years of the Cold War. Other such institutions were the left-wing unions, which were largely in the hands of communists, and an organisation of anti-communist Catholic agitators and workers known as the Groupers, who within the decade would destroy the old Labor Party and establish a Catholic and anti-communist party of their own. It was a period of violent political ferment. There was a referendum in 1950 which was meant to outlaw the Communist Party; it was opposed by the Labor Party, by students and other groups, and the government eventually lost the referendum. The veterans association, the RSL, was deeply conservative in those days and very powerful in public affairs. There was, in fact, a rival group of left-wing veterans, the Returned Servicemens Legion, but it had been disaffiliated and marginalised.

One of the declared enemies of the RSL was what was loosely referred to as the Students. This was the very first generation of young men and women in Australia to get to the university in large numbers. Many of them were working-class, and some of them in fact were returned soldiers. They made up the first generation in Australia of a noisy and articulate youth, a generation of rebels that was university-educated, rather than bohemian, as the rebels of the 20s and 30s had been, though it was bohemian as well: university-educated, bohemian and radical, having discovered Hegel and Marx and alienation and the scrap heap of history, rather than Hell, as a place to which to consign people you no longer agreed with, but also Gorky and Howard Fast and Doris Lessing, all left-wing idols of the time, and existentialism and Sartre and Camus, the idea of The Outsider through Colin Wilson, and early Russian films, like Eisensteins Ten Days That Shook the World and Pudovkins Mother, and Donskoys The Childhood of Maxim Gorky, but also Modernism in all its forms, from Joyce and Faulkner to Dylan Thomas and Stravinsky to Bla Bartk Modernism, which the bohemians of the 1920s, for all their non-conformism, had rejected in Australia.

All this was held as a loose agglomeration of beliefs and interests by a younger generation against the old Australia of the clubs the RSL had set up in more or less every suburb of the larger Australian cities as bastions of what we would have thought of as the great Australian philistinism. Though I should point out that this was still the 50s, and a good many students were also, in fact, members of religious organisations like the Newman Society and the Evangelical Union. Nothing is ever simple. Still, the noisiest of the Students were the sort of left-wing communist sympathisers or fellow travellers who, from the RSL point of view, posed a direct threat to Australian values and even, perhaps, to Australian security. It was the only time I know of in our history when a class called Students had a real presence in Australia and, through the university newspapers, a real and recognised voice. Student unions had become the training ground of emergent politicians, and the university newspapers of emergent writers and intellectuals. It was inevitable, in all this, that Anzac Day should become the focus of bitter argument about Australian aims and values, and all the more because it drew to itself the usual conflict for place and influence between the generations.

Next page